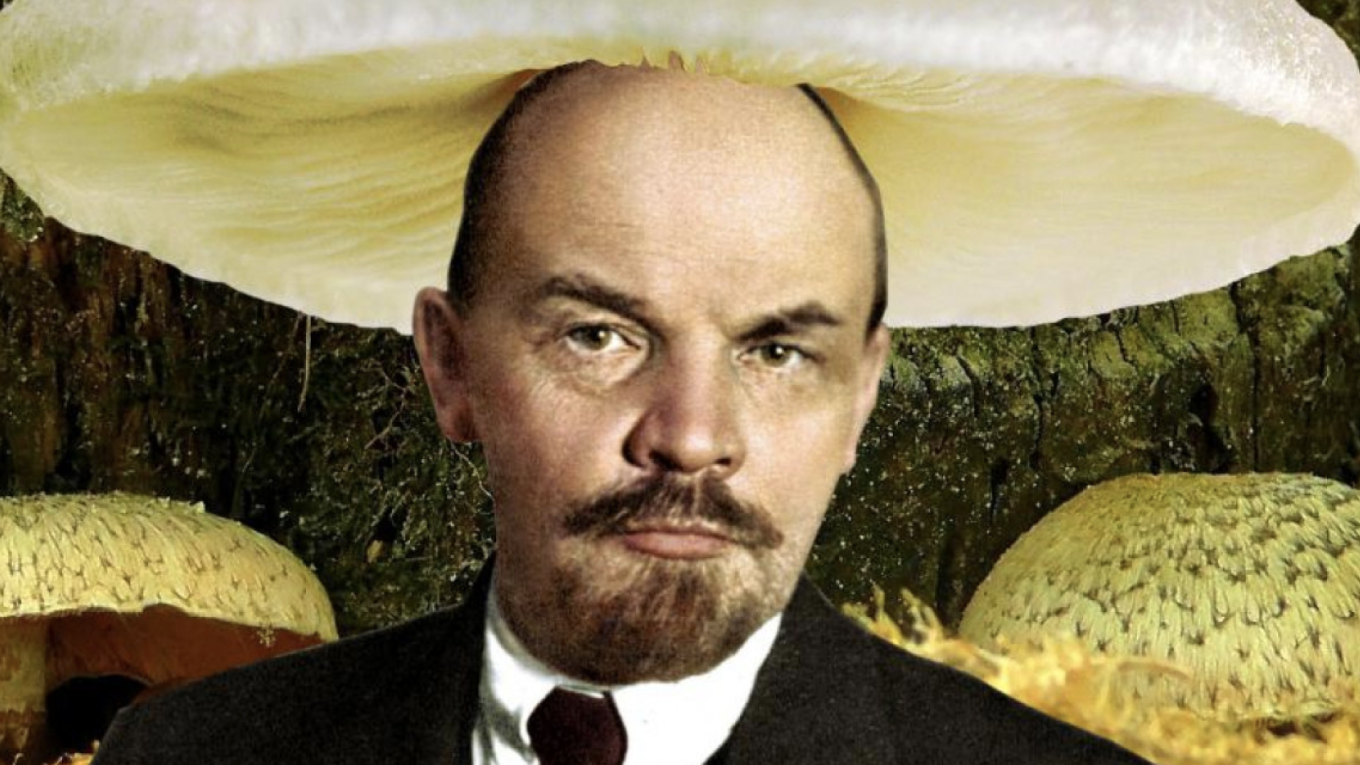

In the dying days of the Soviet Union, a satirical TV show called Fifth Wheel (Pyatoe Koleso) aired a subversive episode that stunned audiences unused to such transgressive broadcasting. Now a classic, "Lenin Was a Mushroom" argued exactly what its title suggested.

Despite using questionable data, fake experts, obviously falsified evidence and lying blatantly throughout, host Sergei Sholokhov and his guest, the musician Sergei Kuryokhin, were nevertheless a little too convincing for their relatively naïve Soviet audience, and many viewers took the satire at face value.

Three decades later, it's worth recalling the incident given that Russian state media is now a place where alternative viewpoints are shunned and where wild conspiracy theories are presented as objective facts.

Just as Sholokhov and Kuryokhin interviewed "scientists" who confirmed that Lenin used hallucinogenic mushrooms, Russia's leading propagandists such as Olga Skabeeva and Vladimir Solovyov regularly invite military and political experts for one sole purpose — to manifest the Kremlin’s agenda in their mock debate.

The discussion of the Bucha massacre in Russian state media, for example, concluded that the images of the massacre were fake. However, it failed to reach a definitive verdict on whether the bodies shown in the images were those of paid actors, mannequins, or victims of the Ukrainian army.

For a few years now, Russian state TV channels have been pushing the narrative that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is a drug addict. Following the invasion of Ukraine, some actual "evidence" to back these claims was eventually produced in the form of blown-up photographs of the Ukrainian president’s desk, which showed a pair of suspect white lines next to a photograph of his family. This "evidence" turned out to be part of the desk’s decorative pattern, though Russian state TV has never corrected its earlier claims.

Russian state TV employed tropes familiar to the conspiracy documentary genre to support its accusations against Zelensky, such as zooming in on the presidential desk to speculate what items may or may not have been present — a technique Kuryokhin himself mockingly employed in "Lenin Was a Mushroom" when he speculated that a "strange object" on Lenin's desk could be a flying saucer, a hallucinogenic cactus or a mushroom.

The subsequent efforts to substantiate the claims made against Ukraine by state media cheerleaders for the war have nevertheless been rather half-hearted. Extravagant scenarios, such as a claim made last year that the Ukrainians were attempting to build a "dirty bomb," are rarely backed up by any evidence, however fabricated it may be. In this case, the images of "Ukrainian reactors" shown on Russian TV ultimately turned out to be photos of Russian reactors.

Just as Sholokhov and Kuryokhin were unable to keep a straight face during much of their "Lenin is a Mushroom" episode — even laughing out loud by its end — the track record of Russia's army of propagandists is an extremely patchy one that would lead any astute viewer to question the content of their claims.

Yet, despite the absurdity and inconsistencies in the Lenin prank, a significant number of viewers seriously entertained the notion that Lenin could have been a mushroom.

One of the most notorious triumphs of Russian anti-Ukrainian propaganda was the widely reported "execution" of a toddler by Ukrainian nationalists in eastern Ukraine at the outset of the war in Donbas in 2014. Just as Soviet TV audiences saw Lenin as too serious a subject for satire, modern Russian audiences saw the alleged incident as too shocking to be made up. Except it was. Since then, the story has enjoyed numerous spin-offs, each stressing the Ukrainian army’s bloodlust for Russian-speaking children in the Donbas, and each so atrocious that few people are minded to ask for proof.

The popular perception of television being synonymous with the state in Russia has barely changed despite the three decades that have passed since the Soviet collapse. Russia's huge TV audience has therefore had its understanding of both itself and the "other" formed by years of repetitive messaging, as evidenced by the fact that the 55+ age group is both the most likely to support the war in Ukraine and the most likely to watch state TV.

While conspiracy theories are far from a uniquely Russian phenomenon, Russia is unique in the sense that conspiracy theories have transcended their traditional marginality and entered the official discourse.

As conspiracy theory researcher Ilya Yablokov has noted, both the Soviet and Russian regimes frequently instrumentalized conspiracy theories for political gain, but only under Putin has this become a mainstream practice.

Various plots against Russia supposedly hatched by the West to either humiliate or destroy the country have helped the Kremlin justify violence both domestically and abroad — for example, NATO or rather the age-old "Anglo-Saxon" compulsion to destroy Russia that it embodies, was used to justify Russia's "preventive strikes" on Ukraine.

Conspiracy theories are also used to justify the Kremlin's intolerance of any form of domestic opposition. As a fortress besieged by enemies, the Russian nation must stand united. Even a hint of political unrest might embolden the legions of "foreign agents" working for the West to destabilize Russian society.

Sadly, for ordinary people who lack any political agency in their own country, it is often easier to rationalize personal misfortune as the result of an international plot against the Russian people than it is to question the narratives relentlessly drummed into the population by state media.

As this mentality meets no resistance from above — indeed, it is actively encouraged — it becomes a vicious circle, being both the root cause of social passivity and atomization as well as its outcome.

Within a mindset that asks "why bother when they have decided everything for me?" Lenin being a mushroom or the entire Western world wanting to destroy Russia doesn't sound quite as absurd.

Despite the similarities between a conspiracy theory created as satire in the 1990s and Russia's domestic media environment today, one significant difference remains. While the Lenin prank heralded a new era in which free speech would be celebrated in all its forms, today's state-sponsored propaganda signals that same era's end: instead of diversity, Russian propaganda preaches unanimity in hate. Instead of playful irony, it is rigidly dogmatic.

Transformed into long hours of pseudo analytics and agitainment on Russian TV, Orwell's Two Minutes Hate has proved adept at bewitching audiences, nurturing resentment toward others, and ultimately, atomizing society.

While the spell cast by the mushroom prank dissipated soon after the show aired, it remains unclear how to break the one cast by the xenophobic indoctrination of Russian state media, which shows no sign of weakening.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.