In the depressed Siberian mining town of Novokuznetsk, stiff competition has broken out among the local night clubs. In a bid to entice partygoers, club owners have switched from happy hour cocktail promotions to the next best thing — offering go-go dancers as racy entertainment. Promoters circulate publicity photos showing sultry women on Instagram and the Russian social network Vkontakte.

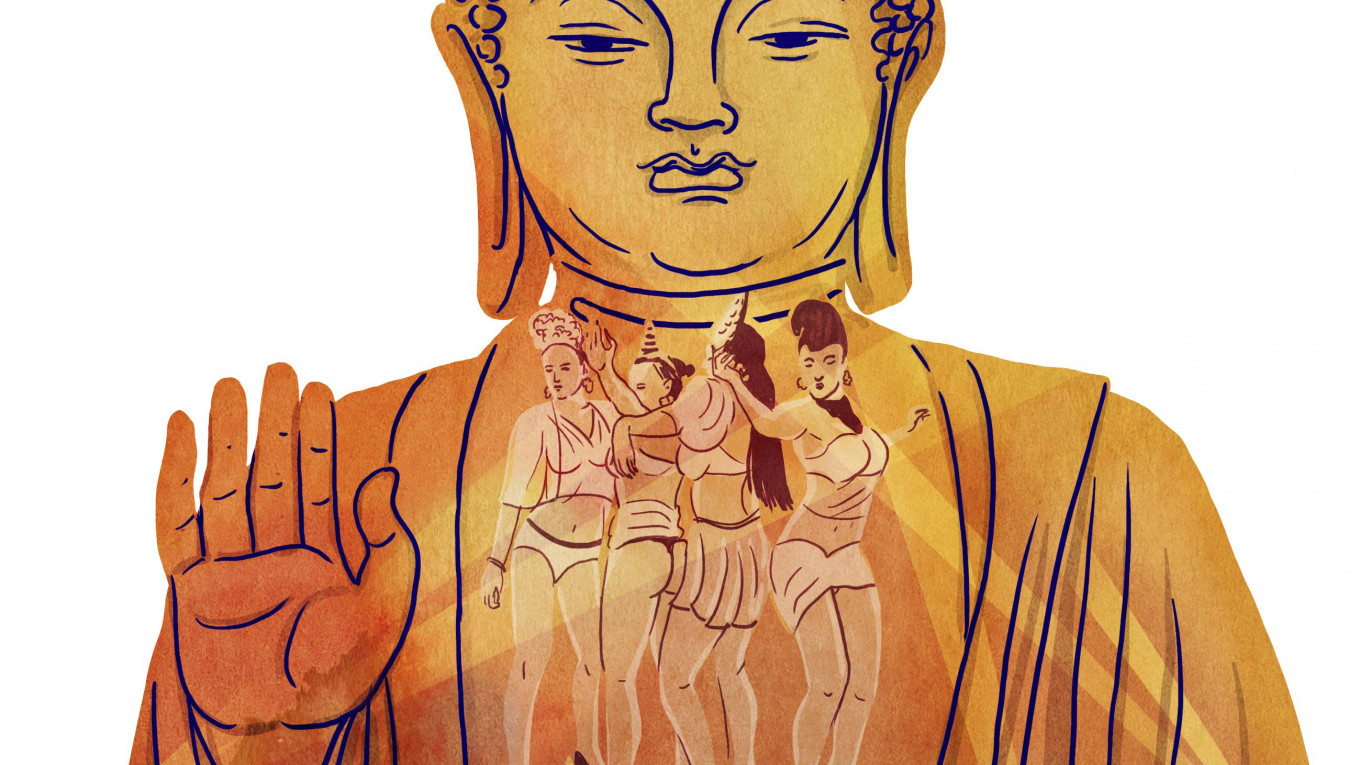

It was here that Valeriya Sanzhieva, a Buddhist from Russia’s Far-Eastern Buryatia region, first saw photos of young women dancing around a statue of the Buddha. The discovery would spark a growing campaign against the Buddha Bar franchise.

“This isn't just about a bar,” Sanzhieva, a housewife, told The Moscow Times. “These bars are associated with vulgar dancing, alcohol, and other pleasures. They have no relation to the Buddha or his followers.”

Sanzhieva is urging Russian Buddhists to fight back against these clubs in an online campaign, which is calling for the closure of Buddha Bars nationwide, including their flagship branches in Moscow and St. Petersburg. More than 7,000 people have already signed.

Sanzhieva says Buddhists can fight club owners profiting from the name and image of the Buddha with a controversial law that makes it illegal to “offend the feelings of religious believers” — a law that conservative Christian Orthodox activists have utilized repeatedly.

The campaign has already scored two major victories: Russian courts in Krasnoyarsk and Novokuznetsk fined multiple bars for allowing scantily-clad women to dance next to statues of the Buddha. The courts also punished the clubs for sharing photos of the act in promotional materials online, ruling that the advertisements offended Russian Buddhists.

But Sanzhieva says Russian judges still have work to do. “Respecting the Buddha's image is an integral part of how I understand my faith,” she says. “We must not remain silent. We are ready to defend our rights in court.”

More from The Moscow Times: Russia's should embrace its religious diversity (Op-Ed).

Forgotten Minority

The roots of Russian Buddhism spread back more than four centuries, yet the country's Buddhist population today is a largely forgotten religious minority.

After suffering widespread persecution in the Soviet Union, the religion is once again growing — and not just in traditional strongholds like Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva. Almost two million people in Russia now self-identify as Buddhist, and many see the fight against Buddha Bars as a sign that their community is finally gaining a voice in Russia.

Others argue against the concept of a Buddhist revival, claiming that believers have merely learned to play by the Kremlin's rules.

“Buddhists have become much less vocal,” says Andrey Terentyev, an academic and the editor of the “Buddhism of Russia” journal. “In the 1990s, Russian Buddhists criticized the government for the Chechen war, and held peace marches, hunger strikes, and demonstrations at Chinese embassies in favor of Tibet. Now everyone is silent.”

More from the Moscow Times: Read about the bitter stand-off between protesters and the Russian Orthodox Church tearing apart a Moscow neighborhood.

Appealing to Putin

To some extent, that compromise has reaped rewards. After decades of Soviet repression, the Russian authorities have begun to reach out to the Buddhist community. One of Russia's most dominant Buddhist schools, the Buryatia-based Traditional Buddhist Sangha, has received a spot on the Kremlin's Religious Cooperation Council. In Moscow alone, there are two new Buddhist temples now under construction, and a special event hosted at the Kremlin in October this year focused specifically on welcoming Buddhists into Russian civil society.

“Buddhism is supported directly by the state in Buddhist regions,” says Alexander Koibagarov, head of the Russian Association of Diamond Way Buddhism. “In places where Buddhists carry out socially useful activities such as art exhibitions, lectures and scientific conferences, we have good working relationships with local administration. They know us and support us.”

Yet the Russian government expects Buddhists’ loyalty in return. While the Kremlin has been happy to welcome Buddhists who fight in the courts alongside conservative, “family-oriented” Orthodox Christians, other Buddhist activists, whose agendas might clash with the government’s positions, haven’t been so lucky.

The Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of many of the world's Buddhists, remains an especially contentious figure in Russia. He last visited in 2004, and authorities in Moscow have repeatedly denied him permission to return ever since. And with every rejected visa application, Chinese officials have publicly thanked the Kremlin.

“Traditionally, all ethnic Buddhists in Russia recognize the Dalai Lama as their spiritual head,” says Terentyev. “Buddhists have already suffered for many years … unable to receive blessings from their spiritual leader.”

For the most part, Russian Buddhists have shouldered these setbacks without complaint, believing that such an approach better follows the key foundations of their religion.

“There's enough aggression, intolerance, and hurt feelings in the world,” says Koibagarov. “We’re not upset by this lack of attention. We do not want to protest and agitate the public. It is far better [for Buddhists] to spend time and energy on meditation: it's far more valuable for believers themselves and for society.”

Yet protests such as Sanzhieva’s show that not all Buddhists agree. And moreover, she believes that working with the Russian government will help further the religion’s cause. Appealing to Russia's Prosecutor General, she says, will be her campaign’s next step.

“There is this idea that Buddhists simply cannot be offended, that we are simply always ‘tolerant.’ But now our spiritual values have become devalued,” Sanzhieva says. “The situation has gone too far.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.