Soon Russia will be marking a rather curious holiday, the “Day of National Unity” on November 4 when a peasant and a prince — Kuzma Minin and Dmitry Pozharsky — supposedly led a volunteer army to liberate Moscow from Polish invaders a half-millennium ago.

It would seem to be a very patriotic and important holiday, but on closer examination proves to be fiction from start to finish. The holiday is dedicated to murky events that took place in the early 17th century, a period no less troubled than our own.

Let’s talk about what really happened 400 years ago, which is quite different from how it is presented today. After Tsar Ivan (the Terrible) struck and killed his older son and then died himself, his younger son Fyodor became tsar. After he and his son Dmitry also died (or were killed) ending the royal line, the country was plunged into what is called the Time of Troubles (1598 to 1613) until Mikhail Romanov was crowned as a new tsar and leader of a new dynasty.

Many scholars regard the Time of Troubles as the natural reaction to the atrocities of Ivan the Terrible. Now some people are in raptures over the tyrant Ivan the Terrible, but at the time things were not so clearcut.

The country, ruined and humiliated as a result of the reign of the mad tyrant, had only just caught its breath after his death and began to come to its senses. The generation of murdered or ruined fathers left their sons depopulated villages along with a fierce hatred of the central government. Many historians consider the Time of Troubles as a kind of civil war that was fomented by the sadistic tsar who divided the population into slaves and enemies — people against slavery.

When the Poles intervened with their Prince Dmitry (the “False Dmitry”), it was actually in response to the discord in the Moscow state. Who could have passed up such a good opportunity? At the same time, it must be recognized that many boyar and noble families greeted the False Dmitry and his followers with open arms. Today someone might say, “What treachery and betrayal of his people!” But it isn’t correct to project today’s realities onto an era almost 500 years in the past. Nor is it right to apply the current understanding of patriotism (real) and “patriotism” (official) to what people had to do to survive in that era.

And besides, siding with a foreign enemy in a fight with a neighbor was a long-standing and largely successful tactic of Russian princes. How many of them were rewarded with a grant to reign from the Tatars after killing off their Russian competitors? There are countless examples. Indeed, the struggle between Russian princes Mikhail of Tver and Yuri of Moscow was over the Khanate’s grant to rule. Ryazan Prince Oleg sided with the Mongolian general Mamai during the battle on the Kulikovo field in 1380. And even Alexander Nevsky allied himself with the Mongols in order to use them to consolidate his personal power.

So it was nothing out of the ordinary for many political groups in Moscow to defect to the side of the Polish invaders. And taking into account how divided the country was — a division that Ivan the Terrible, now deified, was trying to achieve — it was quite predictable.

That’s why simply dividing people of the time into patriots and enemies is not appropriate. After all, some “patriots” of that era had their financial interests in mind, while some “traitors” among the boyars were thinking about what would be best for Russia more than money and titles. It was clear that the Poles wouldn’t last long on the Russian throne, but they had a chance to eliminate the threat of another crazy tsar by introducing a Russian “charter of liberties” of the nobility — a kind of feudal constitution.

Who knows how the country might have evolved if they had won? Here we’d ask our contemporaries to put aside their outrage over the question. You didn’t live during a time when your family could be slaughtered at any moment for the amusement of their tsar. It's not for you to judge.

This “Day of National Unity” is quite a holiday!

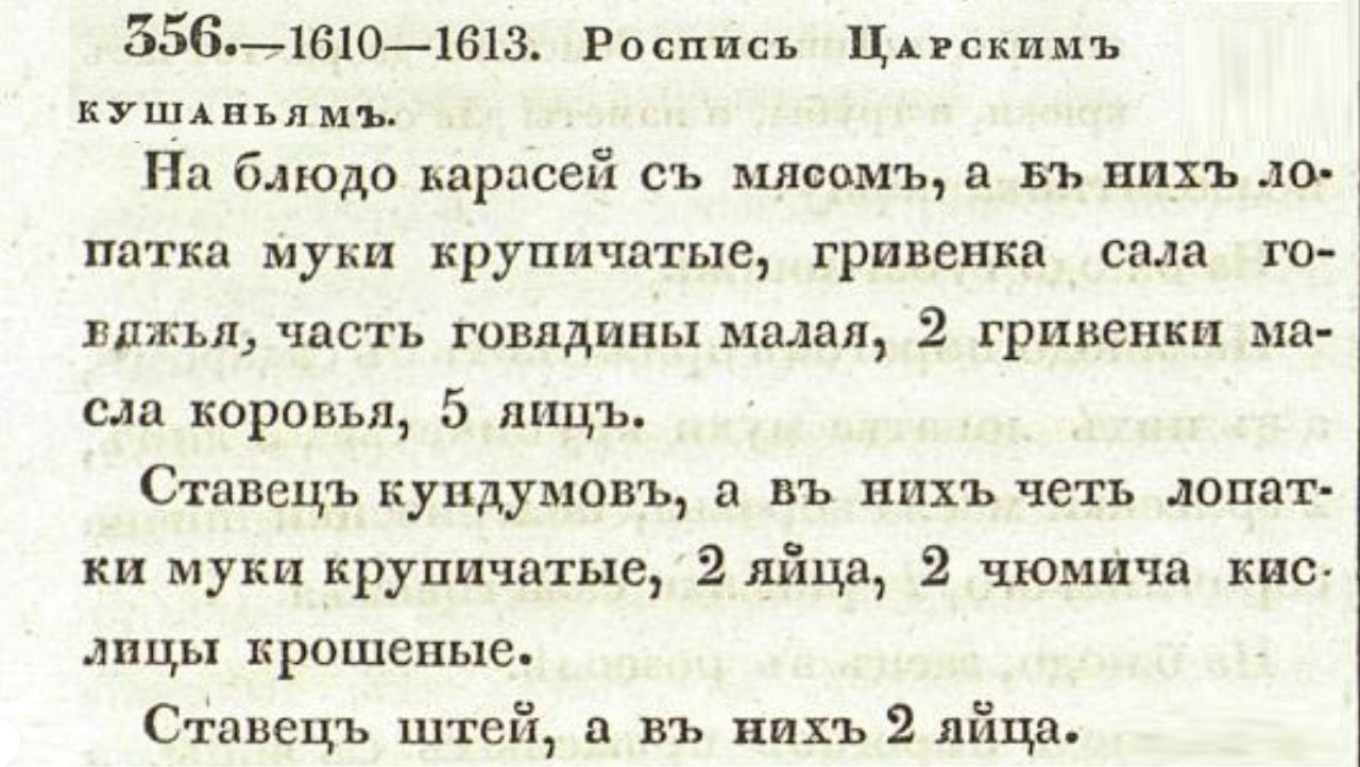

But for all that, we are grateful to that era. The reason is simple. A remarkable document of Russian cuisine came out of the years 1610-13. Called “An Inventory of Dishes Served at the Tsar’s Table,” it is second only to the book “Domostroi” (1550s) as a comprehensive source on Russian cuisine.

It appeared when Vladislav Vasa (son of the Polish king Sigismund) was put on the Moscow throne during the Polish-Swedish intervention. Since the Pole was unfamiliar with Russian customs, a group of boyars compiled it “to familiarize him with how things were done” and to educate him about the subjects he was to rule.

The book contained a list of dishes from the table of the Moscow sovereigns. Supposedly this Catholic foreigner would read it and learn “the customs of the Russian land.”

This book has everything: appetizers; a variety of soups including chicken and duck soup and shchi; meat and fish dishes with the strange name “tavranchuk”; all kinds of breads baked goods — kalachi, pies, karavai, pancakes, fritters, and so on. We learn about products and how they were preserved (such as pickled, spiced and salted fish). We read about Russian sauces and liqueurs and find details about the great number of spices used in royal cuisine, such as saffron, cinnamon and cloves. It shows that Russian cuisine included a lot of foreign dishes. Central Asian manty and the Russian version of pelmeni — kundyumy — are evidence of this.

This is, incidentally, a constant problem when studying Russian cuisine. Information about Russian culinary habits and recipes in distant epochs was mostly in foreign documents and memoirs of foreign ambassadors or merchants. For some reason, our ancestors didn’t take the time to write it down. We are thankful to the Poles that we at least have this. And we are thankful that this book was written during that nightmarish and disjointed time, preserving for us memories of our culinary past.

Kundyumy with Rice and Mushrooms

Kundyumy are the ancient Russian version of Siberian pelmeni, only kundyumy are baked, not boiled. Kundyumy were filled with meat, but also with mushrooms, grains (buckwheat, rice) or with chopped hard-boiled eggs and fish. The dough was made with vegetable oil (hemp or poppy) and hot water. Kundyumy are first baked in the oven to a golden crust, and then baked again in a pot with broth or in sour cream.

Ingredients

For the dough:

- 500 g (1.1 lb or 4 c) wheat flour

- 1 Tbsp vegetable oil

- 245 ml (1 cup) hot water

- 10 g (1 ¾ tsp) salt

For filling

- 200 g (7 oz) fresh porcini mushrooms or 30 g (1 oz) dry mushrooms

- 1 cup boiled rice

- 3 Tbsp of vegetable oil

- 2 hard-boiled eggs

- salt to taste

- sour cream for serving

Instructions

- To prepare the dough, mix vegetable oil with hot water.

- Pour the liquid into the flour and knead the dough.

- Boil the mushrooms and save the mushroom broth.

- Chop eggs finely.

- Chop mushrooms finely and fry together with onions in vegetable oil; mix with rice and chopped eggs. Salt to taste.

- Roll out the dough into a very thin layer — 2 mm (1/16 inch). Do not add flour, the dough should not stick to the table.

- Cut the dough into 7-8 cm (2 ¾-3 inches) squares and form the kundyumy.

- Preheat the oven to 180°C/355°F.

- Grease a tray with vegetable oil and bake the kundyumy in the preheated oven for 15 minutes.

- Transfer to a pot, pour in mushroom broth, salt and put in the oven for 15-25 minutes. Serve with a dollop of sour cream.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.