On the morning of February 24, the day the war began, I went into work as usual. That day I was supposed to give a lecture on aesthetics. I walked into the auditorium and realized that I just couldn't breathe. I couldn't teach a class — for the first time in 15 years.

It was clear that none of the students knew anything yet. Most of them, alas, do not read independent media. I addressed the audience: "Dear colleagues, unfortunately, today is a terrible day.” I told them in general terms what I knew.

Then I started a lecture about aestheticism in art. One of the slides showed Picasso's “Guernica” [Pablo Picasso's painting about the bombing of the Spanish city of Guernica by the German Legion during the Spanish Civil War in 1937]. The first four rows of the audience cried.

That lecture turned out to be my swan song, but I didn't realize it at the time. During the break, many students came up to me. Some hugged me, some expressed alarm. A girl in the audience had relatives in Ivano-Frankovsk, where there were military operations, and her family had been evacuated.

The students asked me to leave time at the end of the class to answer their questions about the history of Russian-Ukrainian relations. This might have been the first time in their lives that many of them raised real questions about the relationship. I said a few words about the events of 2014 and what happened next, whether Russia had objective reasons to fear NATO aggression, and whether the Western world wanted to conquer the country.

At one point, the students in the back rows began to fidget nervously. A heavy-set man had appeared behind them on their stairs. He looked a bit like a security guard, but he wasn’t one — I know them all. He stood with his arms crossed over his big belly and looked at me, shaking his head disapprovingly. I summed up the results of the lecture while this man watched. I never saw him again. I don't know to this day who he was, but it all started with him.

The next lecture to the same students was a week later. I barely slept all week; I was filled with despair, grief, guilt, fear, and tears. I began to stutter and felt dizzy. I felt terrible and apologized to the class if my lecture was not as good as usual.

During the five-minute break, I got a call from the Dean of the Arts Department informing me that one of the students had written a denunciation about me. They threatened to take action if I didn't stop "talking politics" right away because "the university is outside of politics."

I then turned to the audience: "Colleagues, we were just discussing Mamardashvili's concept of the 'medium of effort,' according to which nothing in culture exists by itself, but only through the efforts of people. This also applies to tradition. We have one long tradition, which many people like today, the Gulag tradition. And it, indeed, can only be reproduced through the medium of effort, that is — through denunciation. Someone in this audience has just called the dean's office and demonstrated Mamardashvili’s medium of effort. Thank you. Now I’ll continue.”

The students were reassured that everything was okay, and we went on with the lecture. But I knew that everything had changed.

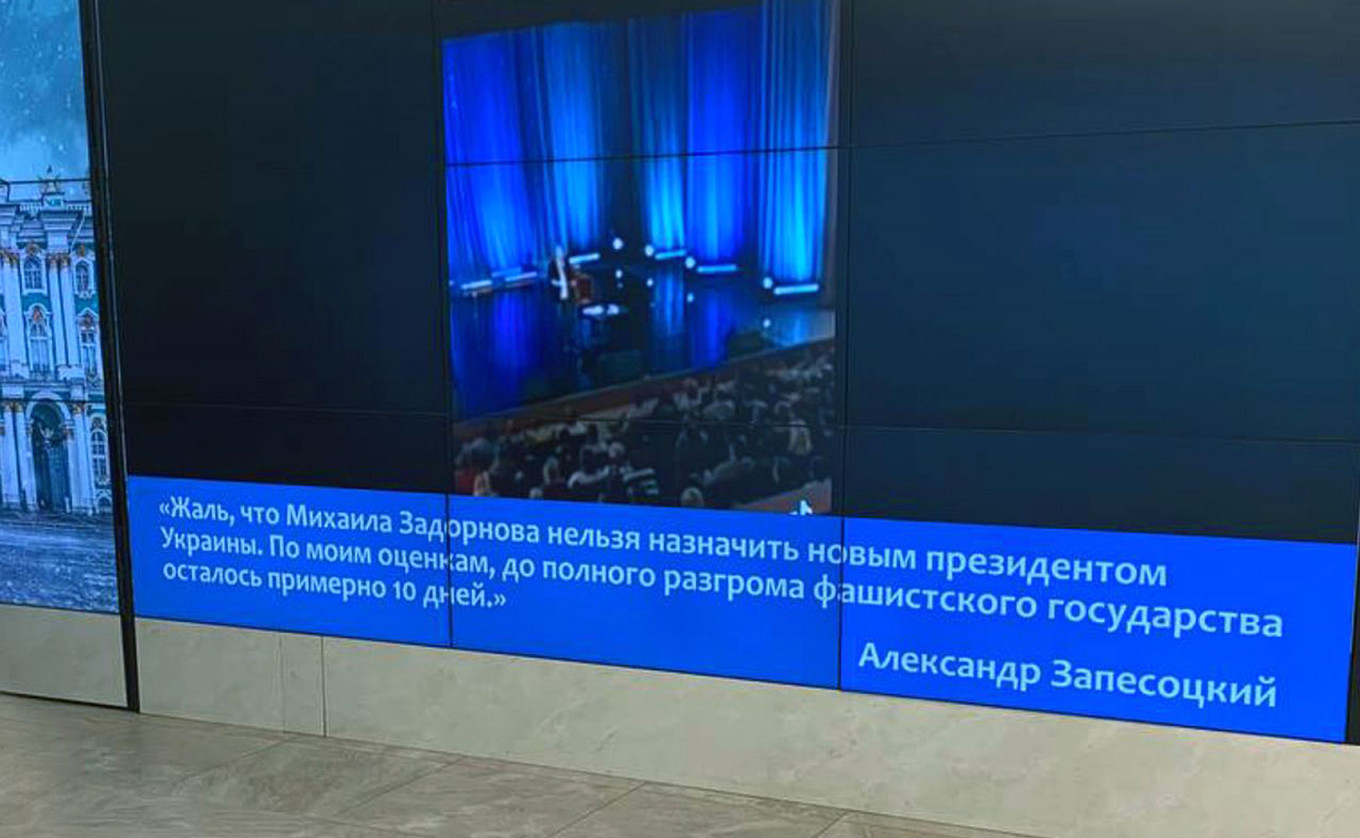

When I walked out of the auditorium, a video was playing on a huge screen in the hallway, showing the rector's quote: "I estimate 10 days to the complete defeat of the fascist regime.”

And that was not the most radical of the videos that were shown on the huge lobby screens.

The university slowly but surely stepped onto the path of propaganda and support for the regime's every move. Soon students began to be taken out of class for political propaganda lessons, censored, and checked for loyalty.

I realized that I couldn't work in such an environment anymore and didn't want to. I decided to quit my job. However, the law required me to work two more weeks.

Students told me that student leaders were asked to report about how I was misusing my position. They asked what they should write so that it wouldn’t harm me. I told them to write what they thought: did my classes have all the subject matter for the program, was the teacher prepared for each class, was there ample material covered and were their visual aids and other media? They realized that I had two options for answering their questions: not to reply at all — and not fulfill my obligations as a teacher — or lie, which I couldn’t do. It would have undermined everything else I’d told them. I had to tell the truth. And besides, when I started out in school I promised myself that I’d work until I had to make a deal with my conscience. I seemed to be at that point.

At my the last lecture I said, "Thank you. You’re excused.” There was a pause. No one left. And then everyone started getting up from their seats, saying words of support and clapping. It lasted about five minutes, then students came down from the amphitheater, shook hands with me and each other, cried and hugged.

At the time I was laid off, my salary at the university wouldn't even feed a cat. Two years ago I earned 17,620 rubles (about $272) as a full-time instructor: six days a week for four or five classes plus the exams that had piled up after the pandemic. It worked out to be about 18 hours a day. I switched to a quarter-time job so I wouldn’t collapse and managed to take on other part-time jobs. My salary was then 4,000 rubles ($62) a month. However, in December it was raised to 14,000 ($215) with all various subsidies.

Lately my paintings have kept me going: I am an art school graduate and can sell my works. But working in contemporary art institutions as an artist is now also difficult because of the censorship. When I tried to exhibit a series of works in memory of the Soviet artist Sergei Paradzhanov as a political prisoner, some people demanded that I take out everything awkward ("too much politics") and leave in the “pretty flowers.” Other people pointed out that Paradzhanov was a homosexual and had no place in the pantheon of great Russians. Very soon it will only be possible to exhibit "Swan Lake."

Sometimes I wash the floors. People tease me about it, but I've never been embarrassed by it.

When I was writing my doctoral thesis I did a lot of cleaning, since I spent all my salary on printouts. I could have gotten some financial aid, but whenever I applied the higher-ups made me write “no” under the question, “Are you writing a doctoral thesis?” They simply didn’t believe that I would write my dissertation and defend it.

No academic is separate from what is happening in the country. When there were protests against the constitutional amendments, most academics did not take part in the actions of civil society. They thought they were in the ivory tower, but they were affected even though they sat in their comfortable offices.

When I was working on my doctoral dissertation and teaching several classes a day, I would spend my one day off in the rain or snow at demonstrations with a bunch of “crazy enthusiasts.” I was infuriated that so many people thought they didn’t have to go to the snowy square and face the national guards’ batons. But if more of us had gone out, this probably would not have happened. Like Sartre wrote: we are responsible for what we did not try to prevent.

Russian society has lost this battle with Leviathan. Society is defeated, crushed and divided. It will go on dying and losing its people. But perhaps some people will get new experience of social activism through this experience of grief, and a new underground will form. But I doubt that this is possible under the powerful current regime.

With everything so hopeless, of course I’m thinking about leaving. But then again: If someone has taken over my house, why should I be the one to leave?

If I stay, I will be a janitor or security guard. I will no longer serve this regime with my mind or my heart, because it turns everything into a deadly weapon. From my lowly position, I will continue to bear witness to the new stages of catastrophe for the future — taking photographs and writing, even if I can’t publish anything.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.