VORONEZH — Retired collective farm workers Vitaly and Valentina Plotnikov, aged 81 and 74, have to grow most of their own food to get by on their combined 35,000 Rubles ($480) monthly pensions. But despite straightened circumstances common to many Russian retirees, they remain strong supporters of President Vladimir Putin.

“We’ve lived through hard times before and life now is the best it’s ever been. Younger people don’t understand that,” said Valentina outside the couple’s rambling cottage on the outskirts of the southern city of Voronezh.

On Sept. 19, Russians will vote in important elections to the country’s State Duma national parliament, the first major test of public opinion since a major crackdown on the country’s opposition movement earlier this year.

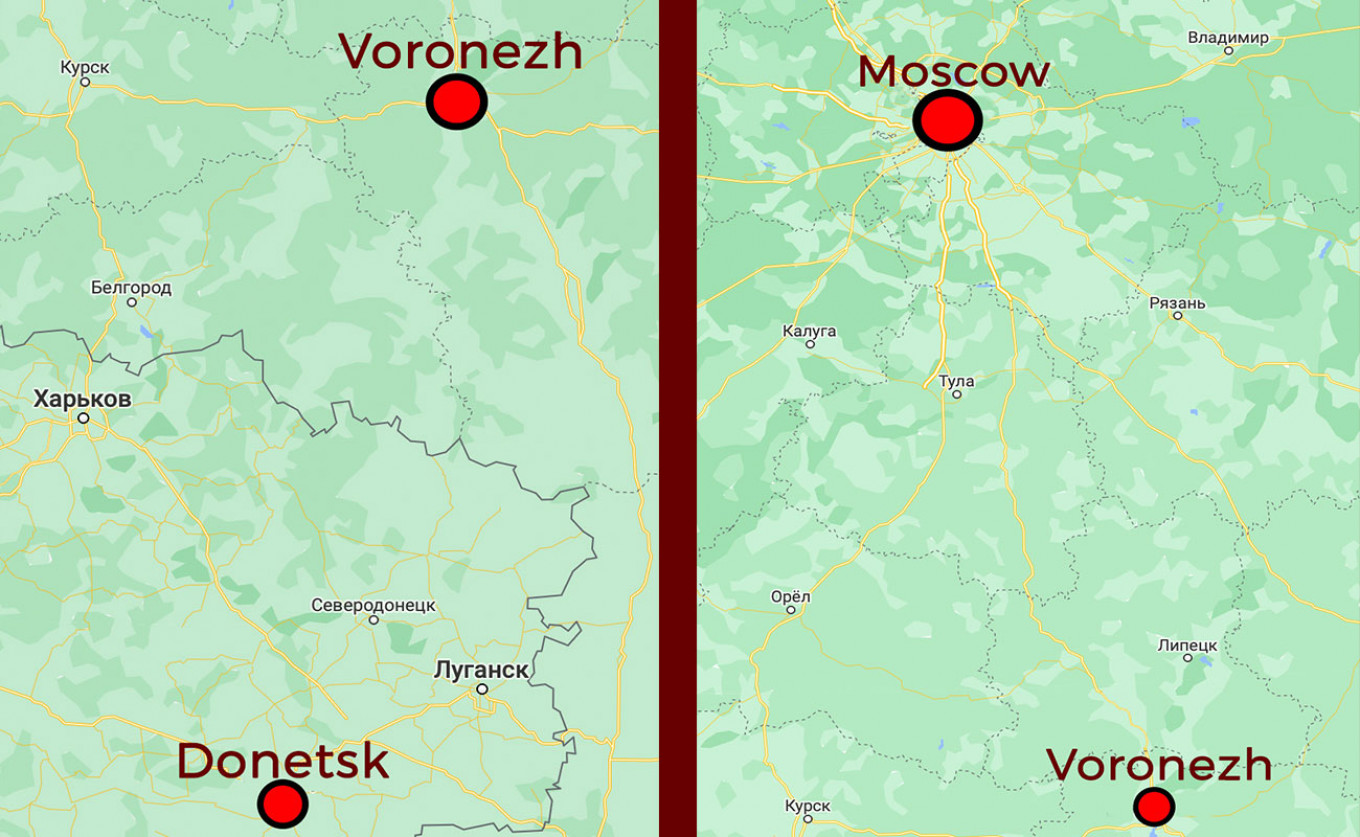

With Russian politics traditionally divided between a handful of large, opposition-leaning cities and a poorer, pro-Kremlin hinterland, Voronezh — an affluent city that increasingly resembles wealthy, liberal Moscow but whose residents remain either loyal to Putin or apathetic — is a bellwether for the national mood.

Even though the ruling, pro-Kremlin United Russia bloc’s polling has hit record lows, the party can still count on the votes of many Russians who, whether out of active support for Putin or simple aversion to the prospect of political instability, plan to back United Russia at the polls.

Though neither Vitaly nor Valentina plan to vote for a ruling party they see as corrupt and complacent, other voters in the city see United Russia as the best bet.

“I’m voting for United Russia of course,” said Alexander Frolov, a 33-year-old businessman in his home in an aging, Soviet-built apartment block in central Voronezh. “What other options are there?”

For much of the past year, both the Kremlin and Russia’s beleaguered opposition have seen the Duma elections as the flagship political event of the year.

Even as United Russia has won every nationwide election it has entered by a large margin, the bloc has never shared Putin’s genuinely broad popularity.

Though around two thirds of Russians approve of Putin personally, his party draws less than half as much support, with both state-run and independent pollsters consistently showing United Russia mired below 30% support among voters, a historic low.

Persistent corruption scandals and an unpopular 2018 pension reform have blighted the prospects of a party that drew 54% of the national vote as recently as 2016, according to experts.

“Most people do not equate United Russia with Putin, even if they know he supports the party,” said Denis Volkov, director of the Levada Center, an independent pollster. “At this point, the party’s voters represent only the most loyal segment of Putin’s electorate.”

The pro-Kremlin bloc’s troubles have been seized on by an opposition smarting from the crushing of a wave of protests that erupted earlier this year after the jailing of Alexei Navalny.

Navalny’s movement, now effectively banned as “extremist,” has largely dissolved in Russia itself, with top aides mostly either jailed or in exile.

However, Navalny allies still hope that their Smart Voting scheme — under which anti-Kremlin voters are encouraged to rally around the candidates most able to defeat the ruling party — might yet be able to secure wins at the polls, despite a history of alleged election rigging and playing fields tilted in favour of United Russia.

But if Smart Voting has delivered occasional wins in liberal-leaning Moscow, Voronezh — Russia’s thirteenth largest city — is a much tougher nut for the opposition to crack.

Once gritty and post-industrial with an ugly reputation for neo-Nazi violence, Voronezh has turned a corner in recent years under a succession of popular, Kremlin-appointed governors.

According to the state-run RIA Novosti news agency, Voronezh now boasts the eighth highest standard of living among Russia’s 85 regions. The city’s restored, pre-revolutionary streets now play host to high-end Moscow supermarket brands and coffee chains.

Meanwhile, Russian IT giants like Yandex and mail.ru have set up large offices in Voronezh, taking advantage of lower costs than in the capital, bringing well-paid jobs to the city.

It’s a story familiar in much of Russia, with living standards having risen markedly, if unevenly, in the two decades since Putin took office.

In Voronezh, this local renaissance saw the region give the president almost 80% of its vote in his 2018 re-election, without the abnormally high turnout that experts say often hints at mass vote rigging.

“We’re still poor compared to Moscow, but things have gotten better here,” said businessman Frolov. “Noticeably so.”

For Frolov, whose formative memories are of the economic collapse of the 1990s and the boom that succeeded it after Putin’s accession to power in 2000, a sense that life is still improving despite a decade of sluggish GDP growth keeps him loyal.

“Vladimir Vladimirovich knows what he’s doing,” he said, using Putin’s patronymic to indicate respect. “He’s much better than what came before him.”

It’s a record of achievement that means Frolov — who as a polling station worker in election season is clear-eyed about the reality of election fraud — excuses Putin’s authoritarian style of government.

“At the end of the day, Russia isn’t Luxembourg. It’s a big, complicated country and needs a strong leader.”

By contrast, for Kirill Ponomarev, a twenty-two-year-old recent graduate of Voronezh State University and Vitaly and Valentina’s grandson, the last two years have shaken his faith in the Putin system.

Previously loyal to the president, who he credited for delivering political stability and strengthening Russia’s institutions, Ponomarev was disappointed by the constitutional amendments passed last year that gave Putin the right to remain in office until 2036.

“I used to think that generational change would lead to gradual political evolution, and that Putin would eventually leave office having built a stable system that would allow us to avoid another revolution,” said Ponomarev.

“But when the amendments to the constitution were passed, it was a clear sign that I was wrong. Instead, we are heading for dictatorship.”

Earlier this year, Ponomarev was arrested and fined for attending an illegal protest against Navalny’s jailing. Though the demonstrations were the largest Voronezh had seen in years, only around 5,000 people turned out in a city of over a million.

“People are apathetic,” said Ponomarev, who plans to cast his ballot in September according to Navalny’s Smart Voting scheme.

“It’s not that Voronezh is a pro-government city. It’s just not a pro-opposition city.”

Such voter apathy might yet be the decisive factor in the ruling bloc keeping its State Duma supermajority.

With much of the electorate having soured on the party, United Russia strategists reportedly see their best chance as keeping turnout low, with no more than 45% bothering to cast ballots.

For those in Voronezh who are voting, events in neighbouring Ukraine often loom large.

Situated only a few hours’ drive from the Ukrainian border and with a Ukrainian-inflected local accent, Voronezh was roiled by Kiev’s 2014 Euromaidan revolution and the outbreak of war in Eastern Ukraine.

For many Voronezh locals, events in Ukraine — where many have family — offered proof of the value of political stability under Vladimir Putin.

Today Voronezh – where cars with license plates bearing the marks of the unrecognized Lugansk and Donetsk People's Republics are a common sight — plays host to thousands of Russian-speaking Ukrainians fleeing war and economic collapse in the Donbas.

In his shabby neighbourhood on Voronezh’s post-industrial left bank, thirty-year-old factory worker Dmitry Yaroshenko recalls cycling to work under Ukrainian army bombardment during the war in his hometown of Kramatorsk, Donetsk region.

“I feel safer and more free here than I ever did in Ukraine,” said Yaroshenko, who took part in pro-Russian unrest in 2014 until his hometown was retaken by the Ukrainian army.

Having taken up Russian citizenship in 2019 under a scheme aimed at East Ukrainian refugees, Yaroshenko plans to go to the polls to reward the man he credits for defending the Donbas and providing for prosperity in Russia.

‘Putin did a lot for us. I live better here than I ever did before. I have a flat of my own and can go on holiday once a year,” said Yaroshenko.

“Life is good here.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.