Chinese officials have visited Russia, the Russian government has announced plans to increase trade volume with China by $200 billion in the next few years and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has expressed interest in increasing its stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft.

So, is Russia pivoting to China or not? This question took on ideological importance when, early in the Ukrainian crisis, the Kremlin stepped up its propaganda, touting China as an alternative to Moscow's partnership with Europe.

Even the most critical take on Russian-Chinese relations must acknowledge that the relative share of Russia's trade with China has tripled since the start of the 21st century, and has increased significantly even in absolute terms. China is Russia's largest trading partner after the European Union. Russia has launched major oil and gas projects with China and already competes with Saudi Arabia as one of Beijing's leading oil suppliers.

At the same time, hopes that Russian-Chinese relations would gain new momentum have not panned out. Russian propaganda's insistence that Moscow was pivoting to Asia only resulted in disappointment when no breakthroughs actually occurred. (The gas contract that Moscow signed with Beijing in 2014 was the result of many years of effort and can hardly be considered a result of that pivot.)

In fact, Russia's negotiations with China on major economic projects continue just as slowly and with just as much exhausting and nerve-racking maneuvering as ever. Under such circumstances, any such project requires at least five to seven years of preparation before it moves into the implementation phase.

This approach is justified to some degree. Major state-owned Chinese companies such as CNPC are essentially a direct extension of the Chinese state bureaucracy. Any future disagreements will very likely shift to the political level, as happened in 2011 when Transneft and Rosneft clashed with CNPC over tariffs for pumping oil through the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline.

In other words, any purely economic dispute over, say, the terms in a contract can become extremely serious and have an impact on national security. That is why Russian leaders in the post-Soviet period have always advocated an extremely cautious, skeptical approach when closing major deals with China in strategically important areas. That approach began to change slowly only a few years prior to the outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis.

Russia had a good opportunity to change that cautious approach to an open door policy in the second half of 2014, when the country's economic prospects looked dismal due to falling oil prices and Western sanctions. It was a time of near panic.

Back then, Moscow was ready to agree to just about anything.Frightened leaders were even prepared to take drastic measures to attract Chinese investment and lending. They were poised to make irreversible decisions that would have, at the least, given China a strong presence in Russia, and at most, allowed it to dominate the Russian fuel and energy sector for decades.

But the Chinese were too slow to react. By mid-2015, the Russian authorities understood that no apocalypse was imminent. Russian government economists now expect economic growth to resume in late 2016, early 2017. Skeptics, however, expect continued stagnation or a sluggish recession, but even they do not predict a radical upheaval.

Thus, despite the fact that the Ukrainian crisis spurred closer bilateral relations with China, especially in industry, no real qualitative changes have taken place.

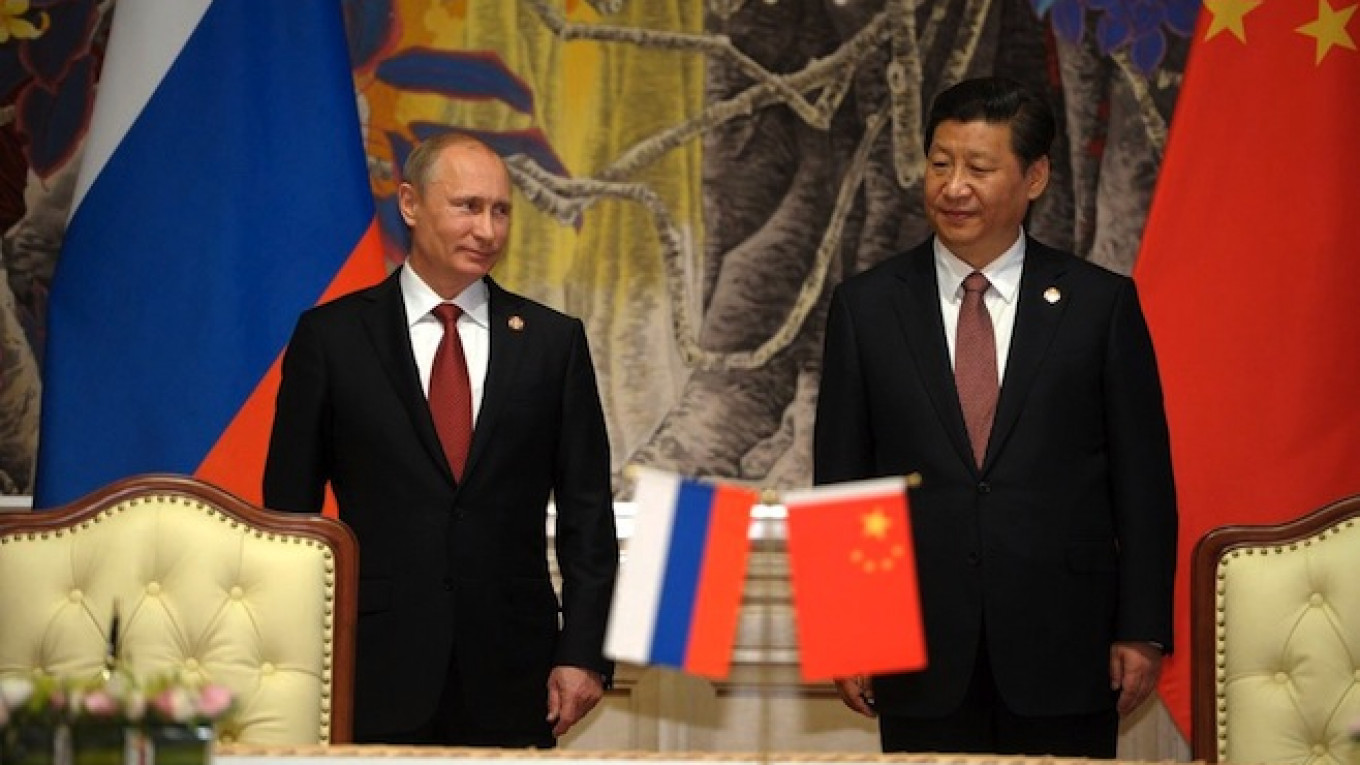

President Vladimir Putin's visit to China in June will probably result in a raft of important intergovernmental agreements to, for example, create wide-body aircraft, construct a high-speed railway between Moscow and Kazan and further develop cooperation on oil and gas. However, no serious changes in Russian-Chinese relations are likely — at least not this year.

There are several reasons for this. First, both the Russian and Chinese ruling elite are split over fundamental issues. The Russian elite have yet to reach a consensus on economic and foreign policy. The Chinese elite are locked in an ongoing debate over future relations with the United States and the possibility of adopting a more assertive foreign policy befitting a superpower.

Second, and more importantly, they both are in a state of uncertainty concerning the outcome of the next U.S. presidential election. Regardless of the outcome, it will lead to major changes in U.S. foreign policy. Those changes might influence the U.S. approach to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, relations with Russia and alliances with countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

Therefore, Russian-Chinese relations might stand on the verge of major changes, but they are unlikely to occur earlier than next year.

Vasily Kashin is Senior Fellow at the Institute of Far Eastern Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.