In July, someone released some sort of gas into our family home.

For about a week, Russian police held watch near our house. When they left I felt at ease, thinking the attackers had considered it a signal. But apparently they didn’t.

In August they set alight my car, which was parked near the house. My father doused the flames so that the house wouldn’t catch fire. Had the car exploded it would have cost him his life. So we left. I cannot risk my parents’ lives.

I don’t think the goal was to kill me or my parents, but once the ball starts rolling such attacks can have unforeseeable consequences. I left because I was horrified by people’s lack of responsibility.

My departure from Russia comes as a surprise — even to me. I always laughed at those who, seven or eight years ago, said Russia was a dangerous country and that Putin was worse than Stalin. Because this was not the case.

Russia was a very violent country in the 20th century. If you compare that to Stalin, we were living in vegetarian times. Putin was never worse than Stalin and he still isn’t.

When Anna Politkovskaya was murdered in 2006 we journalists understood this to be an exception — she had been investigating Chechnya. There were cases where people were poisoned, like Alexander Litvinenko, but we understood that he was a former KGB agent and Putin regarded him as a traitor.

There were highly suspicious cases too: the death of Stephen Curtis during the Yukos trial, or the death of Alexander Perepilichny. The death of Sergei Yushenkov belonged to the category of freak accidents and if it said something about Russia, it was that unbelievable things happen.

Those were deaths, killings, murders. But every time you could account for it and explain why it happened.

Moreover, the authorities seemed unhappy about such incidents. When journalist Oleg Kashin was almost bludgeoned to death in 2010, Dmitry Medvedev spoke out.

I became aware that the things that I had been saying were not welcomed by the Kremlin, to put it mildly, in 2008.

I’d said some nasty things about Russia’s role in the war in Georgia, and accused the president of South Ossetia of being an agent provocateur.

Then I started noticing I was being tailed. One early morning at 4 a.m., I stopped my car in the middle of nowhere and walked up to the car following me, expecting to see some Kremlin youth activists or the FSB.

The passengers looked like they were from the Caucasus. After taking a picture, I ran back to my car. I told Ekho Moskvy editor Alexei Venediktov who, in turn, complained to FSB head Alexander Bortnikov.

He took it seriously. For almost for six months, I was given a security detail and the people who were following me were rounded up. I guess the idea was that if anybody were to kill a Russian journalist it should be the FSB itself and not an outsider.

But still, the authorities and the FSB would not allow a Russian journalist to be touched by somebody without an order from above. That’s how it felt.

Now the situation has changed drastically. A tidal wave of violence has been unleashed, with the attacks around the film “Mathilde” being just one example.

It’s not that Putin or the Kremlin are directly instigating these kinds of attacks. They are winking at those who want to organize them. They’re empowering “local talent,” and those people are given a free pass. Some of them are crazy. Some are in search of some power or want to curry favor.

Of course there is an effort to silence some people. Today, Russians can go to jail for liking or sharing social media posts. But those who attacked me or my parents don’t expect I’ll be so intimidated that I’ll stop writing or broadcasting. Their motivation is to become great in the eyes of Putin.

This doesn’t absolve the Kremlin from responsibility. It makes it worse.

The state should have a monopoly over violence. And by withdrawing the direct connection between the people who perpetrate violence and the Kremlin — which sanctions it, but does not order it — it is renouncing control.

Putin either doesn’t want to, or can’t do anything.

The watershed moment was the murder of Boris Nemtsov. Putin was furious. He saw the murder as an encroachment on his power and it was. Under the guise of serving Putin, the man who gave commands to the Chechen killers showed that he, and not Putin, is all-powerful, because for him real power is the power to kill anybody.

Before, such uncontrolled violence by Russian actors always happened abroad — in Georgia, in eastern Ukraine. Now it is happening inside Russia. It’s ironic: the man who wants to see himself as an all-powerful actor on the foreign stage, is not all-powerful at home.

Two factors have produced this major shift.

For almost sixteen years, Putin’s regime was based on lies, spread through state television, and prosperity from oil money. Now the prosperity is gone and the TV audience has diminished drastically. The Ukraine conflict has lost its effect and the Syria campaign is not a good substitute.

What’s left is violence. When a regime starts failing, it will resort to violence for the simple reason that it is the only effective means of staying in power.

Today’s violence is a symptom that signals the end is nearing. But of course, we don’t know when the end will come.

There is no united society or government that is trying to push me out of Russia. A lot of friends in the political elite have expressed their horror and desire to help. Not everyone is happy with the way things stand.

I’m not revealing where I am because I don’t want to poke the bear. But I’m sure that I’m safe.

I’m continuing my projects in Russia — columns in Novaya Gazeta and my weekly Ekho Moskvy broadcasts. Today there is the internet and my work can be done from a distance.

And I will be back. Once things sort themselves out.

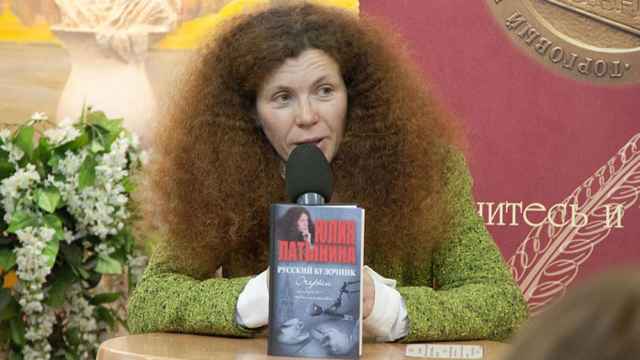

Yulia Latynina has a column in the investigative Novaya Gazeta newspaper and a weekly program on Ekho Moskvy. She is also a former Moscow Times columnist.

The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.