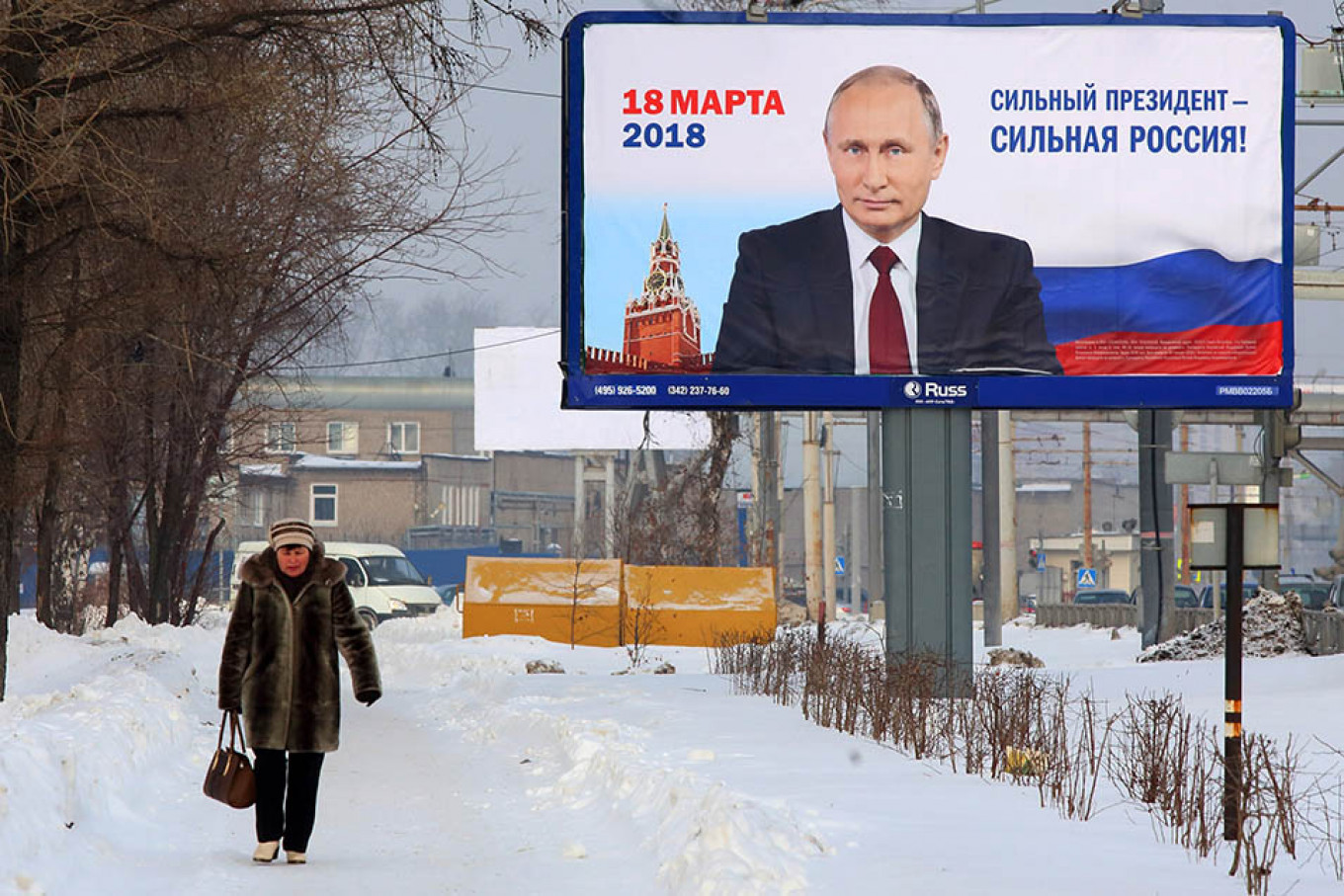

Most Russians think little about the future, possess only a passing knowledge of the political calendar and would have difficulty naming the date of the next presidential election. And, although asking people about events scheduled for five or six years in the future is usually an exercise in futility, recent political events in kindred countries provide a good opportunity to discuss such issues.

The formal resignation from power by the President of Kazakhstan and the change of power in Ukraine, for example, provide cause for Russians to think about their own presidential elections in 2024.

Two scenarios

In late April, we, at the sociological Levada Center conducted focus groups consisting of Muscovites of differing ages as well as attitudes towards Putin.

The pro- and anti-Putin participants mainly discussed two post-election scenarios: 1) the president remains at his post following the next elections, or 2) he steps down and names a successor.

Many people in both camps believed that Putin would not step down, but offered divergent explanations as to why. The Putin supporters felt that the president had more work yet to do, that he was still strong and “had no plans to go anywhere.” They added that no equally “charismatic individuals” capable of replacing Putin had yet appeared on the horizon.

The Putin critics who agreed that he would not relinquish power offered a number of other explanations for this conclusion, including Putin’s love for power and the crucial role he plays in enriching and enabling his close associates. According to this thinking, Putin — like any politician in such a position — would hang onto power “until the last.”

Both apologists and skeptics doubted that Putin would leave office early.

The first group would consider such a move a sign of weakness, if not outright betrayal.

“He should finish what he started,” they argued, “and only then think about leaving!” The second group pointed to the fact that no Russian leader has ever relinquished the reins of power willingly, with the result that very few respondents anticipate a new rendition Yeltsin’s maneuver in 1999.

Few of those surveyed were aware that the Constitution prohibits Putin from serving another term and so most simply assumed he would run for reelection.

Among those who thought Putin might leave office in 2024, most argued that he would do so for health reasons, while others suggested that he might feel compelled to leave after committing serious mistakes in the social sphere during his remaining years in office.

There are already grounds for such a view: Putin’s pension reform was decidedly unpopular and Russians’ incomes are falling. However, very few people believe Putin will step down as a result.

Relocating from the Kremlin

Most respondents who anticipated Putin’s resignation thought he would follow the example of former Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev by naming a successor while retaining his hold on power.

They also consider a “Ukrainian scenario” unlikely in Russia. Most focus group members believed that an opposition candidate would be unable to beat the incumbent president or his hand-picked successor in an election. This opinion was largely based on perceptions of events in Ukraine. Most Russians believe that Ukrainians voted not so much for Volodymyr Zelenskiy as they did against Petro Poroshenko, that they were tired of “war, poverty and corruption” and “mainly wanted a change of leadership.”

As already mentioned, most Russians believe this could only happen here in the event of a social catastrophe, if the current leadership were discredited or if it allowed truly qualified candidates to run in the elections. Today, such a scenario seems unrealistic to most people.

Both the pro- and anti-Putin focus group members agreed that the transfer of power would most likely be accomplished through the naming of a successor and that the ruling authorities themselves would select the individual, not voters.

Putin’s supporters “trust the President’s opinion” and believe that he will “choose a good person for us to vote for.” They see a hand-picked successor as a guarantee that “things won’t get worse,” that the new leader “won’t mess things up,” “will continue Putin’s policies” and “maintain what is already in place.” All of these arguments are strongly reminiscent of the reasons people voted for Dmitry Medvedev in 2008.

Many Putin opponents also agreed that he would first name a successor and that the people would then elect him in national elections. However, there was a sense of futility in their words. “Everything will be decided for us,” they said, “Nobody asks our opinion.” In their view, a democratic transfer of power is only possible in “civilized countries,” a level of development Russia has yet to reach.

What’s more, both the apologists and critics of the current political order agree that even after a successor is named, nothing in Russia will change.

If not Putin

In discussions of a possible successor, Dmitry Medvedev’s name comes up most frequently. Arguments in his favor include the fact that he has already served as president and has the necessary experience, Putin trusts him, and, as the current Prime Minister, he has the greatest chance of becoming president again.

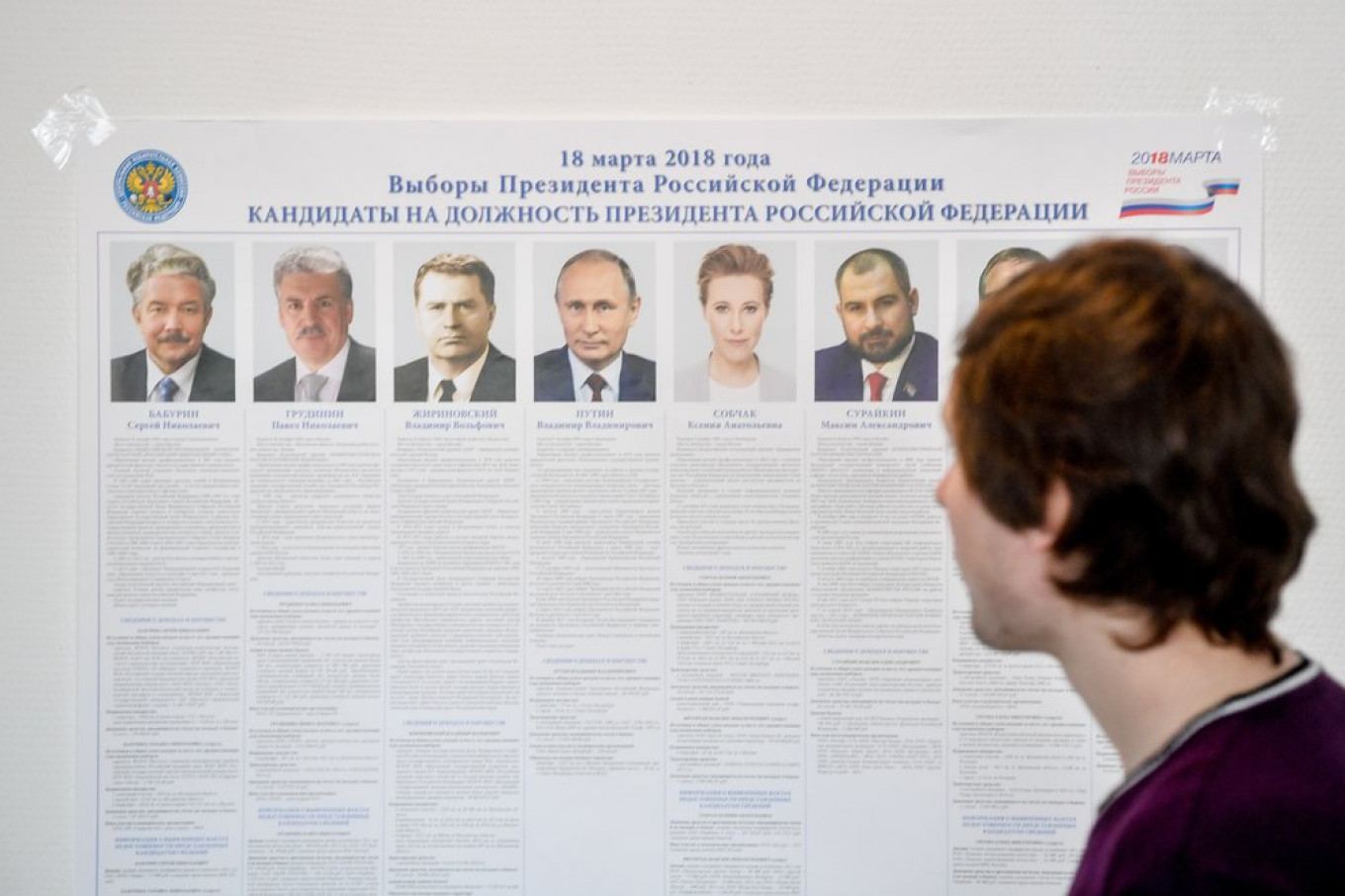

The names of other politicians follow Medvedev’s in order of their confidence ratings. First on the list is Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, whose ratings are second only to Putin’s. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin and the communist Pavel Grudinin are mentioned less frequently.

Shoigu’s strong point is his connection to the army and Sobyanin’s is the fact that he “established order” in the capital and showed himself to be a “strong business executive.”

Grudinin is considered a successful businessman and a good manager. All of them demonstrate the traits of a perfect presidential candidate, while LDPR leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky and Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov are seen as perpetual electoral opponents to the government and not as possible successors.

Many respondents think Putin’s successor will be either a complete unknown or someone beyond the public spotlight. They cite the fact that both Putin and Medvedev began as unknowns and feel that the same thing could happen again. “One year before the elections, a completely new and capable person will appear and everything will be great,” one respondent wrote.

According to others, it will definitely be a “worthy” and “decent” person that the authorities would “select” on behalf of the people. Respondents believed that Putin’s successor would come from either the intelligence services or the military and would definitely have government experience as a governor, regional head or senior advisor.

The general assumption was that the successor would have to be a man, and preferably a hardworking one. According to this argument, a woman simply could not cope with the task because “the country is huge,” Russian politics are tough and the country cannot afford to show weakness in the international arena. Even those who oppose Putin admit that, because of his popularity among the majority of the population, his successor would benefit from voicing loyalty to him.

Anything is possible

It is worth noting that Russians are largely acceptant of either scenario — Putin remaining in power or passing the office to a chosen successor. Most respondents were also ready to see Putin seek another term as president, either because they were unaware that the Constitution forbids it or because they had resigned themselves to the fact that their opinions carry no weight anyway.

The pro-Putin respondents tended to exaggerate the negative consequences of his possible resignation, especially in the international arena. In their opinion, Putin has gained such authority in international affairs that any newcomer would pale by comparison. A clear minority of his apologists even believe that Russia could collapse without him. Most, however, think things will be “worse” after Putin but not disastrous.

Of course, the anti-Putin respondents expressed no grief over the possibility of his departure.

It turns out that in Russia “anything is possible,” to quote the famous phrase of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy — except that those words acquire a different meaning here. In Russia, anything that the ruling authorities propose is possible because most voters agree with their decisions in advance.

A Russian language version of this article was originally published in RBK.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.