Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin might maintain a strong grip on Russia, but since a Sept. 10 election, the ancient fortress on the Moscow River is surrounded by the opposition.

Anti-Putin liberals have filled local councils in the Russian capital’s historic and commercial core as well as a few upmarket residential areas — attaining majorities in 17 of the city’s 125 municipal districts. In some others, the opposition has sizable minorities.

While these councils have only the slightest power to effect change, on par with a New York City community board at best, the symbolism is what really seems to matter to the election’s victors.

In one of Russia’s political paradoxes, it’s often easier for the Kremlin to control the rest of the country than its own capital. It was home to the giant rallies of the late 1980s and the defense of the Russian parliament during the hardliners’ coup of 1991, which precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Moscow has continued to be a hotbed of opposition during Putin’s tenure, even as the federal government pours billions of dollars into urban improvement and new transportation infrastructure.

“The authorities understand that a voter in Moscow requires a more sophisticated approach—straightforward suppression of the opposition doesn’t really work,” said Abbas Gallyamov, a political consultant who used to work for the government supervising regional election campaigns.

This envelopment of the Kremlin by political enemies may serve Putin’s purposes by keeping activists focused on broken elevators and potholes instead of publicizing corruption or seeking higher office.

However, Gallyamov said, the local victories coincide with the rise of protest activity across the country, fueled in part by the main opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, and his long-shot presidential campaign. (It’s unlikely Putin will even allow him to register as a candidate for the March 2018 vote.)

Governing Practice

Dmitry Orlov, a political strategist who sits on the Supreme Council of Putin’s party, United Russia, said the authorities understand the problem posed by the emergence of what he calls “a ring of hostile municipalities” around the Kremlin, and they do their best to neutralize it — sometimes through cooperation, sometimes by trying to split the opposition.

It’s not that the locals have any real power in the face of an authoritarian central government: “The main threat is that the municipalities might transform into centers of protest activity in the run-up to the presidential election,” Orlov said. But suppression is not the answer, he added, since “it will lead to a more aggressive protest movement consolidated around politicians of the Navalny type.”

So for now, while party strategists ponder how to deal with this new reality, the liberals are gaining experience doing something they probably thought impossible under Putin—governing, if just a little bit.

The central administrative area of Moscow includes 10 districts, of which five have majority-opposition councils, four are evenly split, and one is controlled by pro-Kremlin deputies. The historic area centered on the Kremlin, known as Kitay-Gorod, is part of the Tverskoy district, where the opposition holds 10 of 12 seats.

Moscow, like St. Petersburg to the northwest, has federal status, so its mayor functions as a regional governor. Sergei Sobyanin defeated Navalny in 2013 to become Moscow’s mayor in an election the opposition protested as tainted.

From his office in the middle of the city, Sobyanin presides over Moscow’s City Council (which is controlled by Putin allies) and appoints the heads of district council executive boards, or upravas. The upravas oversee the activities of liberal councils like the one in Gagarinsky.

The district (population: 79,000) is a showcase of Soviet urban planning. An area of wide avenues and fortress-like apartment blocks encasing tree-filled courtyards, Gagarinsky incorporates a long belt of landscaped parks running along a bend in the Moscow River. Home to scientific institutions and a Moscow University skyscraper, the district has a large number of children and relatives of scientists who moved there in the 1950s.

Ever since it elected famous dissident Andrei Sakharov to the Soviet parliament in 1989, Gagarinsky, which sits southwest of the Kremlin, has had a reputation as one of the most liberal-leaning districts in the entire country.The gateway to Gagarinsky is a vast square, where the statue of cosmonaut Yury Gagarin faces the Russian Academy of Sciences, itself topped with a shiny, golden metal installation that’s earned the building its nickname: the brains.

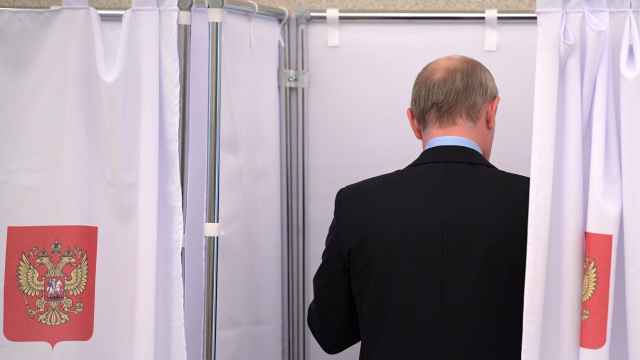

On Sept. 10, Putin arrived there to cast his vote in the Moscow municipal election. All 12 of the deputies who won were nominated by the opposition liberal party Yabloko. United Russia came up empty, though in races for offices representing the district at the national level, Putin’s party won handily.

Putin, 65, is widely expected to seek a fourth term next year, and win. This would extend his presidency to 2024, completing almost a quarter-century in power as the longest-serving Russian ruler since Josef Stalin. Liberal candidates for national and regional offices have repeatedly come under pressure by the government during his tenure.

But none of this stops Yelena Rusakova, who before the September election was the only liberal deputy on the Gagarinsky council. It’s not that the opposition had lost the previous election — she was just the only one running back then. Other members of the council before this year’s liberal sweep were largely nominated by United Russia and the Moscow mayor’s office. Pro-government council slates were often made up of school teachers, military pensioners, and retired public sector employees, and they traditionally didn’t challenge the mayor or the uprava.

Rusakova, 55, a social psychologist, has been an activist since before the Berlin Wall fell. In 1988, she joined Memorial, an organization that researches state-sponsored violence under the former Communist regime (and which has been targeted by Putin’s campaign against “foreign” agents).

These days, she’s affiliated with the liberal Yabloko party and chairs the Gagarinsky council with an absolute majority of fellow activists. Before the election, they had worked to block several construction projects, including a proposed rebuilding of Leninsky Prospekt, a central Moscow thoroughfare that bisects Gagarinsky. Almost all of the council’s new members are middle-aged professionals and academics.

On a Friday evening late last month, the new deputies of the Gagarinsky council took their seats in a cramped room on the ground floor of a Universitetsky Avenue tower. Activists and ordinary residents filled the rest of the room, often interrupting deputies with questions and long-winded addresses. (Apart from Rusakova, the deputies generally don’t get paid.)

Sitting quietly was the newly appointed head of the district’s uprava, Yevgeny Veshnyakov. He oversees the council in Gagarinsky with three deputies and a staff of a few dozen.

The uprava functions as the local arm of the mayor’s office, which approves all decisions regarding construction, transport, urban improvement and trade regulation. The council, meanwhile, can allocate funds only for lower-grade projects such as renovating courtyards and organizing public celebrations. They can question the actions of the uprava and make their own proposals about bigger projects, but they cannot enforce their will.

The previous head of the uprava was fired by Moscow Mayor Sobyanin following the United Russia party’s total defeat in the council elections. After Rusakova introduced Veshnyakov, the session moved on to issues the deputies do have the authority to decide — in this case, the reconstruction of playgrounds and parking lots.

In an interview, Rusakova said she had low expectations about cooperating with the uprava. “These people are sent here to wage a war against us, not to cooperate,” she said. Veshnyakov declined to comment.

Normal people

Local residents seemed cautiously optimistic about their new representatives. Yelena Vorobyeva, a mathematician in her fifties, has spent years lobbying for replacement of a potentially unsafe swing at the children’s playground, but old deputies said there was no money. After the election, things started moving.

“These guys hear us,” she said, adding that she admires the new deputies’ business-like approach. Alexander Bunin, an aviation engineer, has been bogged down in prolonged litigation with the district council over the installation of traffic barriers outside his home. He thinks he’ll be able to resolve his issue with new deputies. “They are, of course, very inexperienced, but at least they are normal people.”

The issues handled by the council may be minuscule, but Rusakova believes this is exactly where the opposition to Putin needs to start. “The state should be rebuilt again from ground zero,” she said, hitting on the key question about her strategy: The ruling party seems content to leave liberals to their devices at the lowest level of governing, but the liberals see their small victories as the beginning of a long road back. Who is right?

One Saturday, Rusakova led a visitor to a local patch of greenery known as Molodyozhnaya Ulitsa. “Look at this park,” she said. The council has had to fight repeatedly to prevent development, pushed by private investors, that would eradicate the little oasis among the grim apartment blocks. “This is a favorite place for locals — but for government officials, it’s a potential construction site.”

Before the latest election, the Kremlin had full control of all 125 municipalities in the capital, with only a few opposition deputies on a handful of councils. Now, with 17 opposition-run districts and some 13 councils evenly split, the tide at the lowest level of government may be turning.

Moscow is a trendsetter. It’s always a step ahead, but the rest of the country eventually catches up

The belt of opposition-controlled councils stretches from the southwest of Moscow across the city center to the north. Dozens of other districts with their first opposition members are concentrated in the leafier, western neighborhoods favored by the middle class. Districts in the grittier, working-class east are solidly pro-Putin.

Local revolution

Government supporters, meanwhile, aren’t sitting idly by as this tiny rebellion brews. Members of Facebook groups tied to the Gagarinsky district and Rusakova began to attract sponsored posts linking to a story by the government-funded RAPSI news agency. In it, Rusakova and her allies were accused of “destabilizing the situation” by protesting construction projects, some of which they fear will damage the area’s verdant character.

Gagarinsky is filled with trees dating back to the 1950s. Every Saturday, Rusakova and her fellow council members put on rubber boots and grab shovels for their weekend routine — filling in a trench dug out by a developer. It was cut to run six kilometers of cable from a power station to an apartment block in another district. The construction was frozen, but the trench remains, leaving roots exposed as the ice-cold Moscow winter approaches, threatening the trees planted by the grandparents of current residents.

“People need really good self-organization to oppose this system and eventually, to change it,” Rusakova said. “Where we see hotbeds of self-organization, we can also see instances when the government backs off.” This is what happened with the trench. When people first gathered to fill it, the uprava sent in the police. But when more people came the following Saturday, it sent shovels and few janitors to give a hand.

North of the Kremlin, a man who spent years trying to stage a peaceful anti-Putin revolution now occupies a key office in the local government of Krasnoselsky (population 48,500), a district centered around three major railway stations. Like Rusakova in Gagarinsky, Ilya Yashin, a close ally of slain opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, now heads a council of like-minded deputies.

After moving into his office, Yashin, 34, took down Putin’s portrait and replaced it with a vintage 1989 election poster for Solidarity, the Polish anti-Communist movement, featuring John Wayne as “the new sheriff in town.” A bookcase is still filled with United Russia literature left by his predecessors.

After almost two decades of street protests aimed at bringing about a Ukraine-style revolution, Yashin is now focusing on the same small-bore issues as Rusakova — repairing old apartment buildings, neighborhood beautification, and opposing unpopular construction projects.

Yashin’s new duties verge on the ironic, given that he helped write reports critical of Russia’s wars in Ukraine and Chechnya: He heads the local military draft commission and supervises the work of district police, whose chief must report to him on his achievements. “I have been delivered into his police department in handcuffs several times,” Yashin said, adding that the police chief has already asked him for help finding apartments for his officers.

Yashin’s new job is indeed a reversal from his old life of street protests. But the example of neighboring Ukraine, which saw two revolutions in the span of a decade, makes him wonder why successful revolutionaries aren’t as good at conducting crucial reforms. “It is easy to gather a group of passionate people and oust a dictator, but life doesn’t stop there, and you need to manage the country in a different way,”, he said.

In Yashin’s view, what he’s doing now might be more important than getting rid of Putin. “If there is no functional self-government, then — soon after revolution — you’ll need to make another revolution,” Yashin said. “I want to show that even at this low level, we can achieve results,” he said.

As optimistic as these local politicians may be, the rest of the country is a different story.

Moscow’s moderate political climate contrasts with more conservative, pro-Putin sentiment elsewhere. Gallyamov, the expert on Russian politics, said Putin tolerates his Moscow opponents in the same way China tolerates dissent in Hong Kong. The thinking is that, out in the suburbs and beyond, the Kremlin doesn’t really have anything to worry about.

Yashin disagrees. “Moscow is a trendsetter. It’s always a step ahead,” he said. “But the rest of the country eventually catches up.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.