It was one of the first hot days of spring, but dozens of the men gathered in Moscow’s central Pushkin Square were clad in fur hats, heavy military fatigues and leather boots. Some also carried a leather accessory: the traditional nagaika whip.

The men were Cossacks who had come, they would later say, to see the May 5 protest ahead of President Vladimir Putin’s fourth inauguration for themselves. But they did more than just watch. Soon after the meeting began, the men charged at the protesters, tearing away their signs, punching them and lashing them with the leather whips.

Within a day, before some of the protesters’ wounds had even begun to heal, a news report surfaced that one of the Cossack units had been trained by Moscow city authorities in handling large street gatherings. The report also said that the group had received funding from the Moscow mayor’s office totalling 16 million rubles (about $261,000).

The controversy did not stop there. The reporters also found that the same group — the Сentral Cossack Battalion — would be helping Russia’s police ensure security in Moscow during next month’s FIFA World Cup soccer tournament.

It is “insanity,” said Maxim Shevchenko, a pro-Kremlin political commentator and journalist. Earlier, Shevchenko had resigned from his post on Russia’s Human Rights Council over the government's decision to deploy the Cossacks on Pushkin Square. “We’ve seen how they ‘provide security,’” he told The Moscow Times. “Why do we need Cossacks when we have police and the National Guard?”

Law and order

For Cossacks, enforcing their conservative interpretation of law and order has long been a point of pride. Tracing their heritage back to the ferocious horsemen of Russia’s southern steppes who protected the frontier for the Russian Empire during the tsarist era, many Cossacks today still believe that they are essential to an orderly state.

Lashing someone with a nagaika resolved things better than — I’m sorry to say — any judge.

“In traditional Cossack areas before 1917, there never were any police,” says Mikhail Bespalov, the first deputy ataman — a Cossack leader — of the Great Don Army. “If someone beat their wife or if someone stole a pig, the Cossacks decided what to do. And as a rule, lashing someone with a nagaika resolved things better than — I’m sorry to say — any judge.”

Loyal to the tsars and the Orthodox Church, the Cossacks fought against the Bolsheviks on the losing side of the 1917 civil war. In the subsequent years, they were nearly wiped out, with hundreds of thousands killed by the Soviet regime.

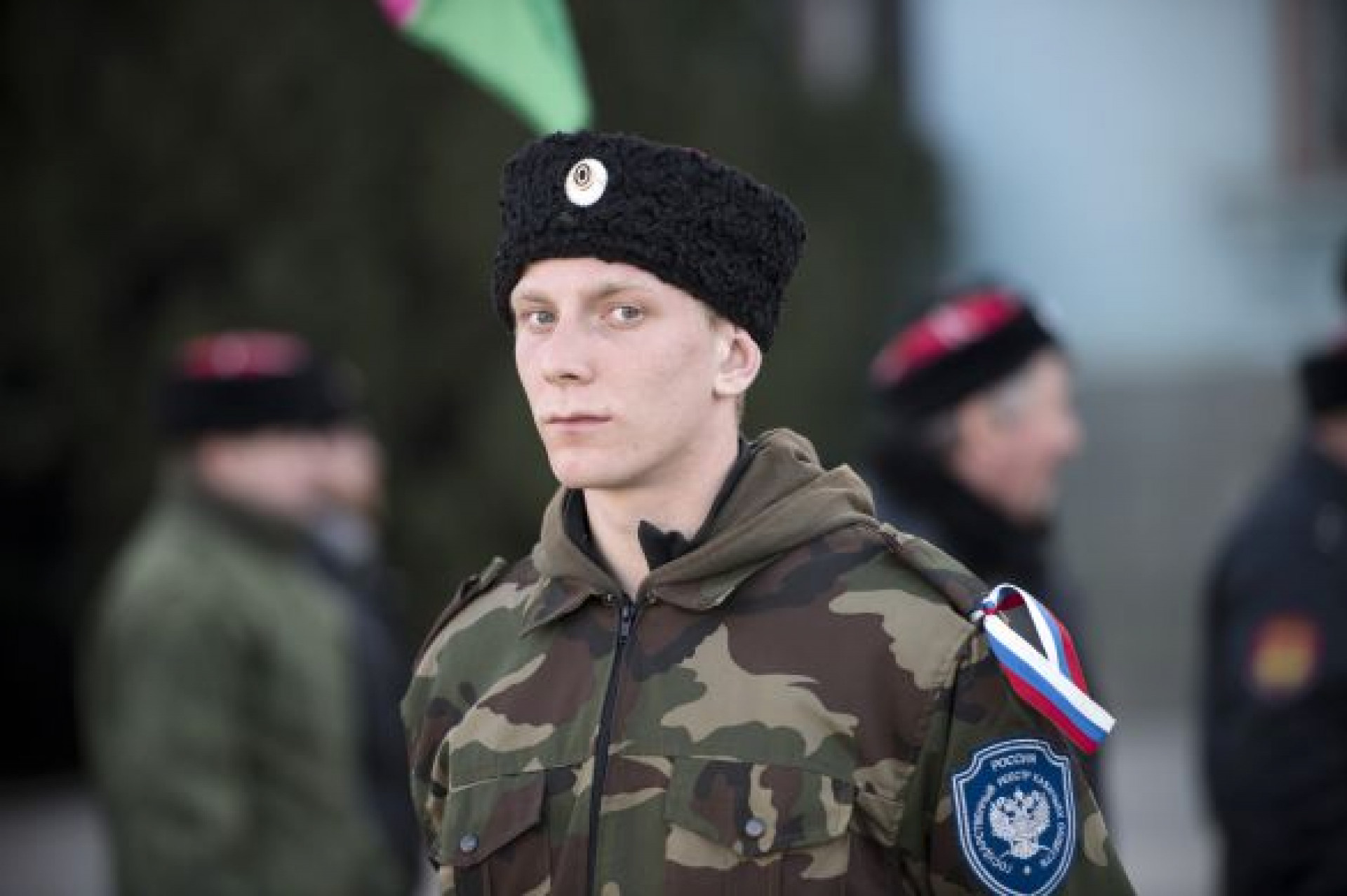

Still, the Cossacks’ combat lifestyle and codes of honor have lived on in the public imagination. Under Putin, they have enjoyed a resurgence as a symbol of his militaristic brand of nationalism. Today, even men with dubious claims to Cossack heritage who are attracted by the lifestyle can find traditional garb — including nagaikas — for sale in shops across the country.

“There are a lot of former police and military types who don’t know what to do with themselves after they have completed their service,” Nikolai Mitrokhin, who researches contemporary Russian nationalism at the University of Eastern Finland, told The Moscow Times. “The Cossack movement speaks to them. They get to put on a uniform and protect something.”

For many years, the Russian government was unsure about what to do with these vigilante types, says Mitrokhin. Until, in 2005, a government register was created, allowing them to win state tenders to provide security at public events. In doing so, the government also formalized a jack-of-all-trades and, at times, extralegal tool, says Mitrokhin.

Mitrokhin pointed to the weeks leading up to the annexation of Crimea in 2014 as an example of how Cossacks have benefited the Kremlin, when an estimated 1,000 Cossacks from across Russia’s southern regions were sent to the peninsula.

“Once they arrived, they pretended to be locals to provide a veneer of wide public support, and they also used physical violence to strong-arm Crimeans into supporting Russian intervention,” he said.

It is a vigilantism that is embedded in Cossack history. During the tsarist era, Cossacks carried out campaigns against minorities, including Muslims and Jews, at the behest of the authorities. And today, government officials often still see Cossacks in the same illicit tradition.

When then-Krasnodar governor Alexander Tkachev formed a patrol of 1,000 Cossacks in 2012, he noted that they would not be limited by the law in the same way as police. “What you cannot do,” Tkachev told a gathering of law enforcement officials, “a Cossack can.”

World Cup peacekeepers?

Moscow is not the only city where Cossacks will provide security during the World Cup. In the southern cities Rostov-on-Don and Volgograd, Bespalov of the Great Don Army, a government registered unit, says that 330 Cossacks, including some on horseback, will be divided between the two cities to provide security.

“We will welcome tourists with joy and with smiles on our faces,” he said by phone, noting that the Cossacks have learned a handful of words in several foreign languages in preparation. “We want to show them that Russia is a welcoming place.”

In recent weeks, Bespalov said his men have been attending training sessions with local police and with the Emergency Situations Ministry. “It will be hot, both in emotions and in temperature,” he said. “We need to be ready to help out fans in case they need us.”

Asked how the men were selected, Bespalov said that to first join the Don Cossacks, candidates must answer questions about their heritage in detail, pass an exam on Cossack history and a six-month probation period. Of 1,200 members, about a quarter were selected for the World Cup after strict Interior Ministry criminal background checks, Bespalov said.

Requests for comment on the Cossacks’ participation in World Cup security provision to local police departments, the Interior Ministry and the National Guard were all referred to FIFA. FIFA, in turn, referred The Moscow Times to the authorities.

“FIFA is in regular contact with Russian and international authorities concerning security matters for the 2018 FIFA World Cup,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. Reached by phone, Andrei Shustrov, the first deputy ataman of the Central Cossack Battalion, said, “I don’t have time for interviews,” then hung up.

Getting off easy

The 2018 World Cup will not be the Cossacks’ first international sporting event on the government pay roll. During the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, they made headlines after whipping members of Pussy Riot. When Russian police failed to prosecute the perpetrators, Pussy Riot appealed to the European Court of Human Rights.

After the May 5 protest, the Cossacks have yet again mostly escaped punishment.

The Investigative Committee is currently considering two complaints against Cossacks; another was fined 1,000 rubles (about $16) by a Moscow court for foul language in public, though he escaped punishment for whipping protestors.

“Legally, Cossacks in these instances are representatives of law enforcement officials,” said Pavel Chikov, director of the Agora international human rights group. “If something like this happens during the World Cup, I would urge people to appeal to the courts, just like if a policeman uses excessive force.”

After the anti-Putin protests on May 5, however, even self-identifying Cossacks have questions about whether the militia units can be trusted to handle public events.

Mikhail Popov, a 20-year-old university student in Moscow who identifies as Cossack, was horrified after witnessing what happened on Pushkin Square. With three other activists, he launched a Telegram channel “Beware of them,” where the group has been outing the men who perpetrated the violence. Although the majority of Cossacks there that day were non-government registered, Popov sees both types as frauds.

“Most of the government-registered Cossacks aren’t real Cossacks,” he said. “We see all of these people simply as wanting to join a militia. It’s a farce.”

Unfortunately for Popov, though, the Russian public — let alone foreign tourists — is unable to recognize true Cossack identity. As Alexander Verkhovsky, director of the Moscow-based SOVA Center, which tracks extremism, put it, “From an outsider’s point of view, what difference does it make who is real and who is not?”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.