The working hours of Civic Assistance Committee are long over, but its waiting room, a modest space on the first floor of a residential building in northern Moscow, is still crowded. Men and women of African and Middle Eastern descent — most of them already in winter clothes — patiently sit and wait to be seen.

Svetlana Gannushkina, the Chair and driving force behind the Committee, is always on the move. In her early 70s, she is full of life — answering phone calls, talking to her colleagues and dealing with documents.

She smiles when asked about reports that she was considered for the Nobel peace prize.

“To be honest, I dreaded the thought,” she says. “I wouldn’t have been able to keep up with the flow of people they’d have sent my way.”

In the absence of proper institutional support, Gannushkina’s NGO has become the first line of assistance to desperate refugees in Russia. “I have several Iranians here who converted to Christianity and came to [the northern Russian city of] Murmansk seeking asylum. What did the people in Murmansk do? You guessed it: they put the refugees on a plane and sent them to Gannushkina.”

In 2015 alone, 2,276 people applied to Gannushkina’s Committee for assistance. The vast majority of them — 1,546 — were refugees. But the numbers represent a drop in the ocean. There are probably some 100,000 people in Russia eligible for receiving a proper refugee status, says Gannushkina. And only 770 individuals have ever been granted asylum.

“When I say this number at conferences, I’m always afraid translators will get confused and add ’thousand’ to it,” she says. “It is difficult to wrap one’s head around the fact that there are just 770 official refugees living in Russia.”

A Long Struggle

Gannushkina realized that working with refugees was her calling 27 years ago, in January 1989. At the time, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh region was unravelling.

“There were protests in Yerevan — people flooding the streets demanding that barbarian Azerbaijanis leave the region and stop the bloodbath they had started,” says the activist. “It was so inspiring, so democratic and progressive, and I instinctively decided to go there.”

A last minute change of mind, however, saw the activist return her tickets and book a ticket to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan — the country on the other side of the conflict. This journey was to change the course of her activism.

In the course of her six-day trip, Gannushkina came face to face with Azerbaijani refugees — those who had been forced out of Armenian villages and stripped of their homes, money, and possessions. The refugees told gruesome stories.

“They told me how armed Armenians came at night, and gave them three days to leave. They walked to the border on foot. There was a woman among them, and I saw her holding a tiny corpse of her son who had frozen to death during the journey. It was monstrous. It determined my fate,” Gannushkina says.

A year later, violent pogroms, this time in Baku itself, forced almost 40,000 Armenians to flee to Moscow. These were the first refugees Gannushkina and her fellow activists helped. “No one wanted to deal with them and [Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev could only say they would all go back at some point,” she says. “But in the meantime, the refugees had nowhere to go.”

Both the Azerbaijani and the Armenian consulates disavowed them. The Armenian consulate, however, didn’t have the guts to throw the refugees out onto the street, so for a while many of them lived in the consulate building, sleeping in corridors. Together with other activists, Gannushkina began helping them — bringing them food, clothing, and assisting them with getting medical treatment.

Later that year, the Soviet government issued a decree stating that refugees should be “cleared out” of Moscow and St. Petersburg (Leningrad at the time). Moscow authorities refused to comply, and instead gave the refugees temporary places to live — generally rooms in hotels and sanatoriums. That was the extent of attempts to integrate refugees.

“After more than a quarter of a century, some of those refugees are still in the same hotels, still hoping to get a Russian passport,” Gannushkina says. They are not the only ones in limbo. In fact, they are joined by other waves of post-Soviet refugees: the people who fled from Georgia and Abkhazia in 1993-1994, the Ukrainians that came to Russia in 2014, and now, the Syrians who are fleeing a five-year-long civil war.

None have been successfully integrated.

A Failing System

Russia has all the legal tools to deal with refugees. In 1967, the country joined the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; a convention which defined the term “refugee” and outlined clear criteria for those who can apply for refugee status.

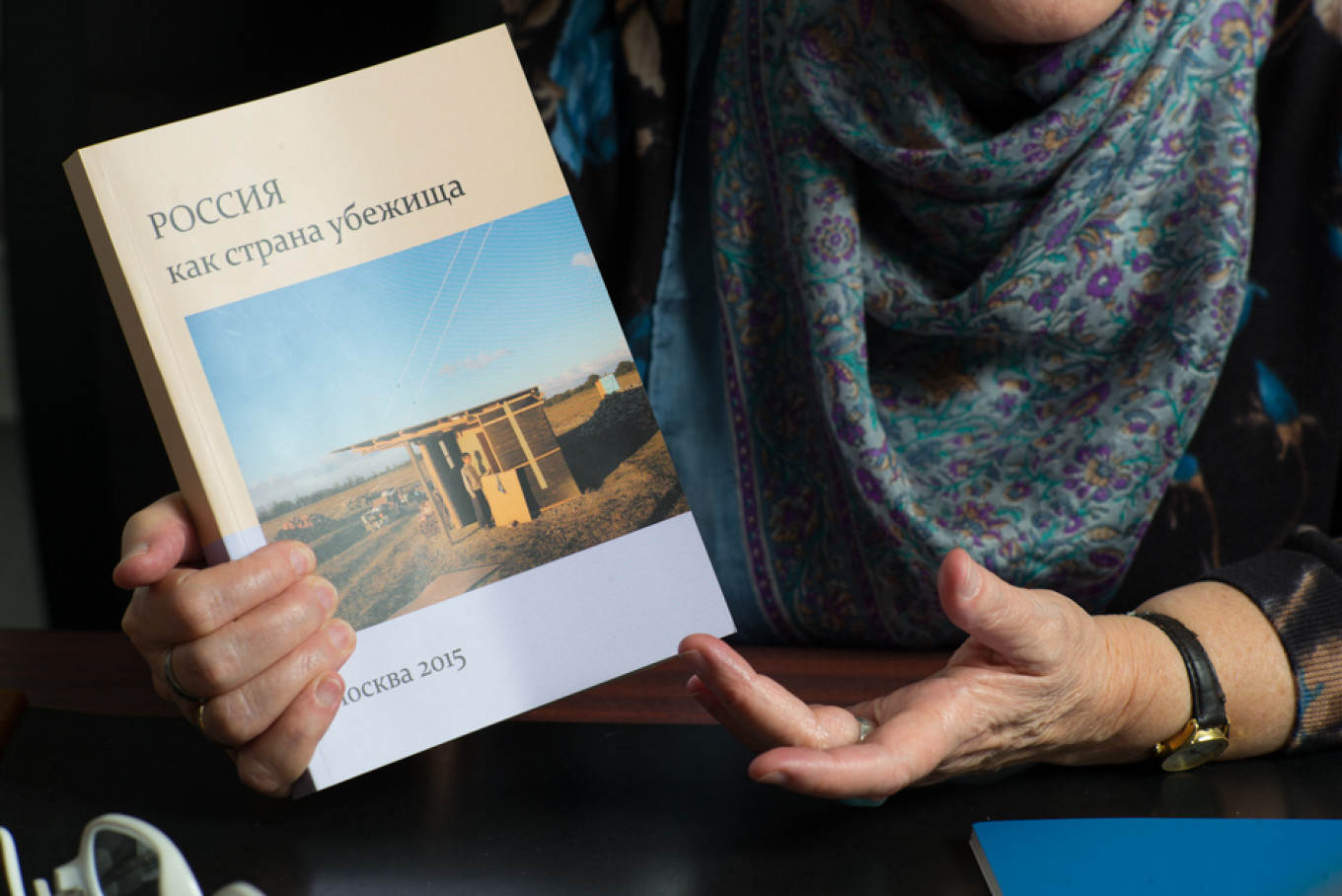

Since then, Russia has also created its own law on refugees — quite a good one, Gannushkina is keen to point out — setting out the procedures for obtaining refugee status.

The problem is that the legislation doesn’t work.

In practice, awards of refugee status are arbitrary, says Gannushkina — determined by Russian authorities who ask themselves if a person really “deserves” it. “Obtaining a refugee status should not be a question of deserving it, but of being eligible according to the legal criteria.”

The Syrians that end up in Russia should automatically be eligible for asylum, Gannushkina says — they are, after all, obviously fleeing a war. In practice, Russian officials have tended not to agree. Of the approximately 10,000 Syrian nationals currently in Russia, only two have been granted refugee status. Some 1,000 migrants have been granted temporary asylum, but this is a status that expires after one year, and Russian authorities are usually not inclined to extend the term.

The breakdown of Russia’s 770 refugees makes for interesting reading. Aside from the two Syrians, there are 300 Afghans and 300 Ukrainians. Most of the Ukrainians were special police officers implicated in deadly clashes during the EuroMaidan revolution.

“Then there are a few isolated cases — for example, one U.S. national and two North Koreans,” Gannushkina says.

The situation with North Korean refugees remains particularly tense after Russia and North Korea signed an extradition treaty in November 2015. Since then, Russia has been reluctant to grant North Koreans asylum. The consequences have been, on occasion, fatal.

Gannushkina says her organization tried to stop Russia signing the treaty.

“The authorities told us not to worry, because the North Korean government promised to treat refugees well, but we knew differently,” she says. “We found out that one of the refugees we tried to help and failed was roped onto a moving train. That was how they ’delivered him to his homeland’ — or what was left of him, to be exact.”

When it comes to refugees, the default position for Russian officialdom is an “indifference bordering on cruelty.” The reason for this, the activist believes, is a widening gap between government and society.

“Russian officials set themselves in opposition to the people, and that includes refugees. They ask why they should give people they don’t know anything. And, besides, why should they be accommodating when our president has told them we can’t be like Europe [which accepted millions of Syrian refugees in 2015].”

Foreign Agents

As a former member of the Presidential Human Rights Council, and member of the government commission on migration, Gannushkina is well-connected. She has had several opportunities to raise the issues of refugees and migrants in Russia in front of top-rank Kremlin officials, including the president. Her committee works closely with the country’s migration authorities, and some cases are solved “manually” — by contacting officials who are able to pull some strings and help out.

However, good connections only go so far: Gannushkina admits that dealing with a system that is unwilling to concede mistakes is obviously difficult.

Last year, life became even harder when the Civic Assistance Committee was declared a “foreign agent.” It was a long-awaited upshot of the infamous 2012 law, which obliged NGOs receiving foreign funding and engaging in vaguely defined “political activity” to register as such.

Once an NGO is labelled “foreign agent,” it becomes subject to additional government scrutiny and huge bureaucratic burdens. Last year, several prominent NGOs either shut down, or, unwilling to work under a label that carries strong espionage connotations, gave up foreign funding.

Gannushkina’s Committee has never hidden the fact that is has received foreign funding. The “political activity” that got them in trouble was work analysing migration laws for possible corruption and Gannushkina’s own participation in the government’s migration commission.

Not being able to afford giving up foreign funding, the Committee chose instead to carry the label with humor and almost with pride.

“The law obliges us to write everywhere that we are foreign agents,” Gannushkina says. “So we wrote on our website: yes, we are agents for foreigners... and these ones in particular, linking our statement to photos of individual asylum seekers and their children.”

Jokes aside, the “foreign agent” label has made life difficult for Gannushkina and her colleagues. Not only has the paper workload increased exponentially, but some of the Committee’s regular partners have refused to work with a ’foreign agent.’

Gannushkina says her work will continue regardless.

“We can’t give up and put a closed sign on our door that says ‘we gave in to depression,’” she says. “The pessimists of this world see a dark tunnel, but the optimists see a light at the end of the tunnel, and the realists understand that this light is coming from a train that is bearing down on them.”

Where does Gannushkina stand in this scheme?

“I suppose I’m the woman trying to pull as many people as possible from under the train,” she says.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.