Seventy-five years ago this past Saturday, Soviet NKVD and Red Army soldiers, acting on the orders of General Secretary Josef Stalin, began Operation Lentil, also known in the region as Aardakh.

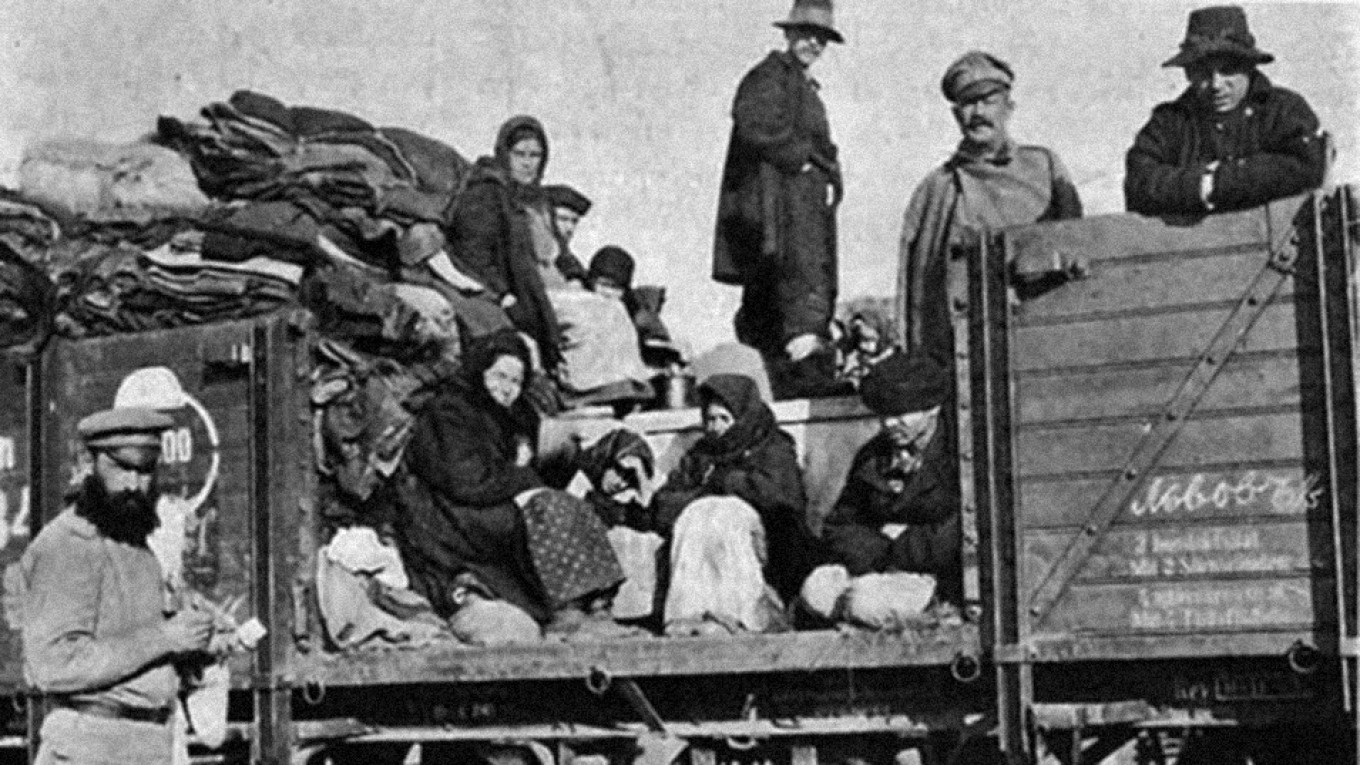

Stalin had ruled that the entirety of the Chechen and Ingush populations were traitors, collaborating with the Nazi soldiers that had invaded the Soviet Union but never reached the Vainakh lands. Nearly half a million people were loaded into industrial railcars and shipped off from their ancestral homeland, bound for Central Asia. Within a year, more than one-third of them would be dead.

Stalin’s goal was not to eliminate the Vainakh: it was to erase them. They would not be rounded up and shot, but sent far from their homes.

Tragedy often goes hand-in-hand with irony, and in this case, it was on a scale hard to comprehend.

At the same time their entire populace was being liquidated for betrayal, some 50,000 Chechens and Ingush were fighting on the front lines in the Red Army.

Five Chechens were awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union, the USSR’s highest military honor, during the war. The last, Abuhadji Idrisov, was given his on June 3, 1944, three months after the deportation. The family he was fighting to defend was already gone.

Eventually, the Vainakh were rehabilitated by Nikita Khrushchev, their names officially cleared and their return from exile sanctioned in 1957. Many returned to find their homes occupied by others, and they remained treated with suspicion. Unlike other ethnic republics, the head of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR remained a Russian until 1989.

The Soviet collapse brought unspeakable tragedy back to one-half of their people, with two brutal wars in Chechnya again devastating its people scarcely a generation after their return.

In the years after their repatriation, the exile had often been a taboo topic, the events too sensitive and the authorities too oppressive to make discussing those events a reasonable prospect.

The flawed but hopeful years of Ichkeria, the independent state the Chechens established following the Soviet collapse, brought the exile into the public sphere for the first time, expanding upon the limited perestroika-era commemorations with a chance for the nation to process what had been inflicted upon them and grieve openly.

A humble monument was erected in downtown Grozny in 1990, a raised fist grasping a sword with the words: “Dölkhur dats! Dukhur dats! Dits a diir dats!” (We won’t cry! We won’t break! And we will not forget!)

But such a horrific tragedy, ordered by the then-leadership in Moscow and arbitrarily inflicted upon its own people, did not sit comfortably alongside the version of history the new Chechen leadership wanted to promote. Ramzan Kadyrov, a former militant turned Kremlin lackey who ascended to Chechnya’s pro-Russian leadership in 2004, was keen on pushing a new narrative.

In this version, Chechnya and its people had joined the Russian Empire voluntarily several hundred years ago, participating in its hardships and glories like the October Revolution and Great Patriotic War.

There was no clear way to reconcile the deportation with this narrative. It was quietly banned: the raised-fist monument was disassembled in 2008, and the annual public commemoration of the Aardakh had been canceled since 2011. This year, for the first time in eight years, Kadyrov allowed a small commemoration, though it was overshadowed by celebrations of Russia’s Defender of the Fatherland Day at which the Chechen leader spoke.

The fight for the justice of history continues elsewhere. In 2014, a Chechen filmmaker planned to debut his feature-length production “Ordered to Forget” at a Moscow film festival.

The film focuses on the Haibakh massacre, one of the most brutal events of the deportation, during which NKVD agents in the highland village of Haibakh, concerned about their ability to transport the inhabitants to the main collection, resolved their scheduling dilemma by simply locking all 700 residents in a barn and burning them alive.

Catching word of the film’s contents, Russia’s Culture Ministry reacted in Soviet fashion: the film was deemed to present “historical falsehoods” that would “incite ethnic hatred,” and was promptly banned.

In Ingushetia, the deportation is remembered solemnly, including at the Monument to the Victims of Political Repression, a haunting structure depicting nine traditional Vainakh towers bound together with chains.

The world community has provided some consolation. In 2004, the European Union recognized Stalin’s deportation of the Chechens and Ingush as a genocide. But there is little reason to hope that Russia will follow suit.

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has been more focused on casting past catastrophes as great triumphs in which to take pride. The most recent to receive this treatment has been the Soviet war in Afghanistan, now presented as a sweeping triumph in Russian history.

In the meantime, there is little justice to be found for the victims of the deportation, many still alive, and their descendants today. Like the Circassians in 1864 and the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire in 1915, the Vainakh today are yet another aggrieved victim of genocide by an empire that branded them inconvenient traitors — one of the small, proud nations of the Caucasus that have suffered so much at the hands of their would-be conquerors.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.