Russia is starting to look like a normal country and 2018 will take it another few steps toward putting its emerging market status behind it.

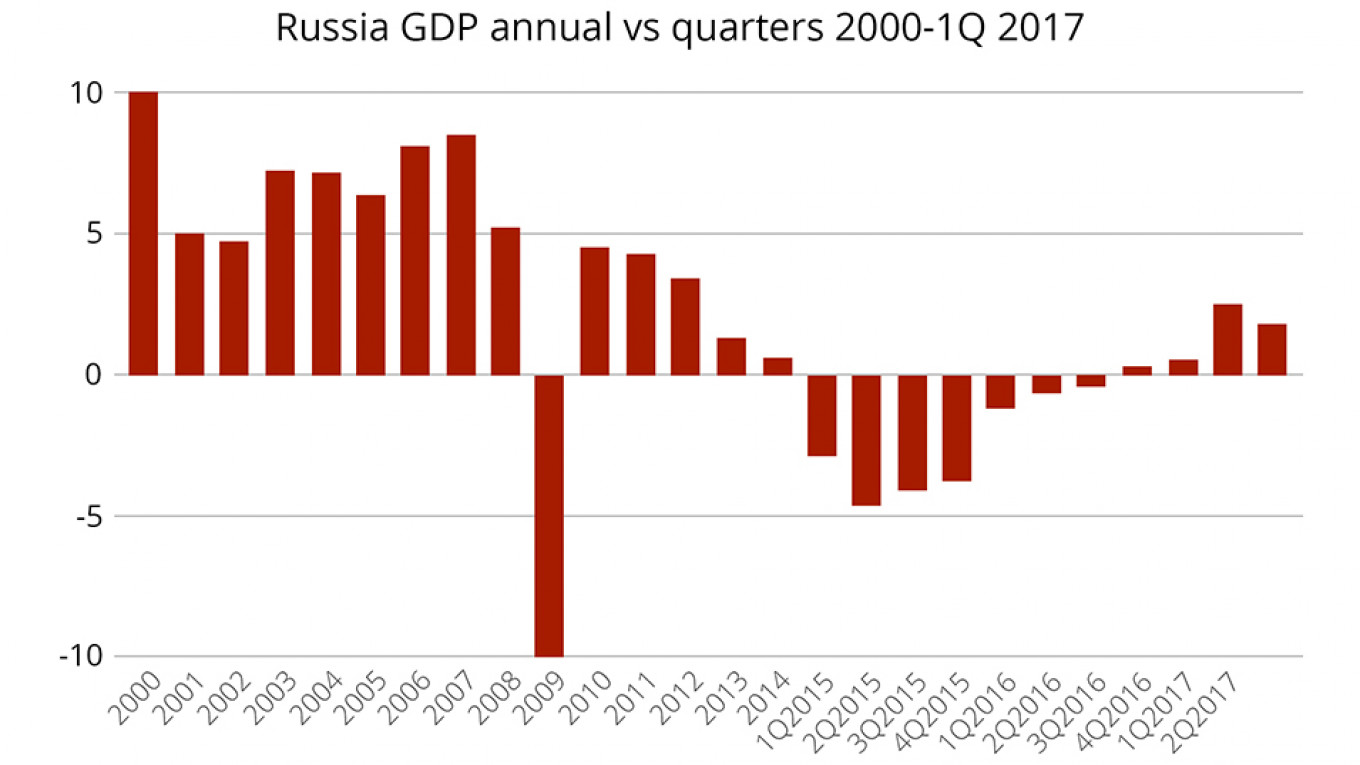

Having climbed out of a two-year recession in 2017, Russia is still far from the blistering 6-8 percent annual growth of the boom years in the early 2000s. But the outlook for 2018 is gradual improvement and growth as high as 2 percent.

Digging into the details, more and more indicators are starting to look like developed market numbers. Inflation in December was at a record low of 2.5 percent and unemployment was at 5.1 percent. Income per capita in 2016 was $22,540, on a par with some European Union countries.

The outlier that marks out Russia as not quite there yet is interest rates.The Central Bank policy rate is still nearly 8 percent — an emerging market level. But that too is expected to fall and could go as low as 4-5 percent in 2018.

However, economic recovery remains fragile and in desperate need of deep structural reforms.

Russia’s petro-driven growth model was exhausted by 2013, long before the clash with the West over Ukraine, economic sanctions and hysteria over alleged U.S. election meddling. Most observers hope reforms will be launched after presidential elections in March that are expected to hand Vladimir Putin another six years in power.

Putin’s choice of economic model will be the main event of the year and set Russia’s course for the next decade.

The alternatives are stark. Former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin wants investment in infrastructure and society to bolster productivity. Business ombudsman Boris Titov and the StolypinClub, a policy lobby group which he heads, prefer a massive borrow-and-spend campaign to kick-start growth. Putin may surprise, but Titov’s star seems to be rising.

Crisis of confidence

Beneath the structural constraints is another problem. Russia is suffering from a crisis of confidence. People and companies have money but are not willing to spend it.

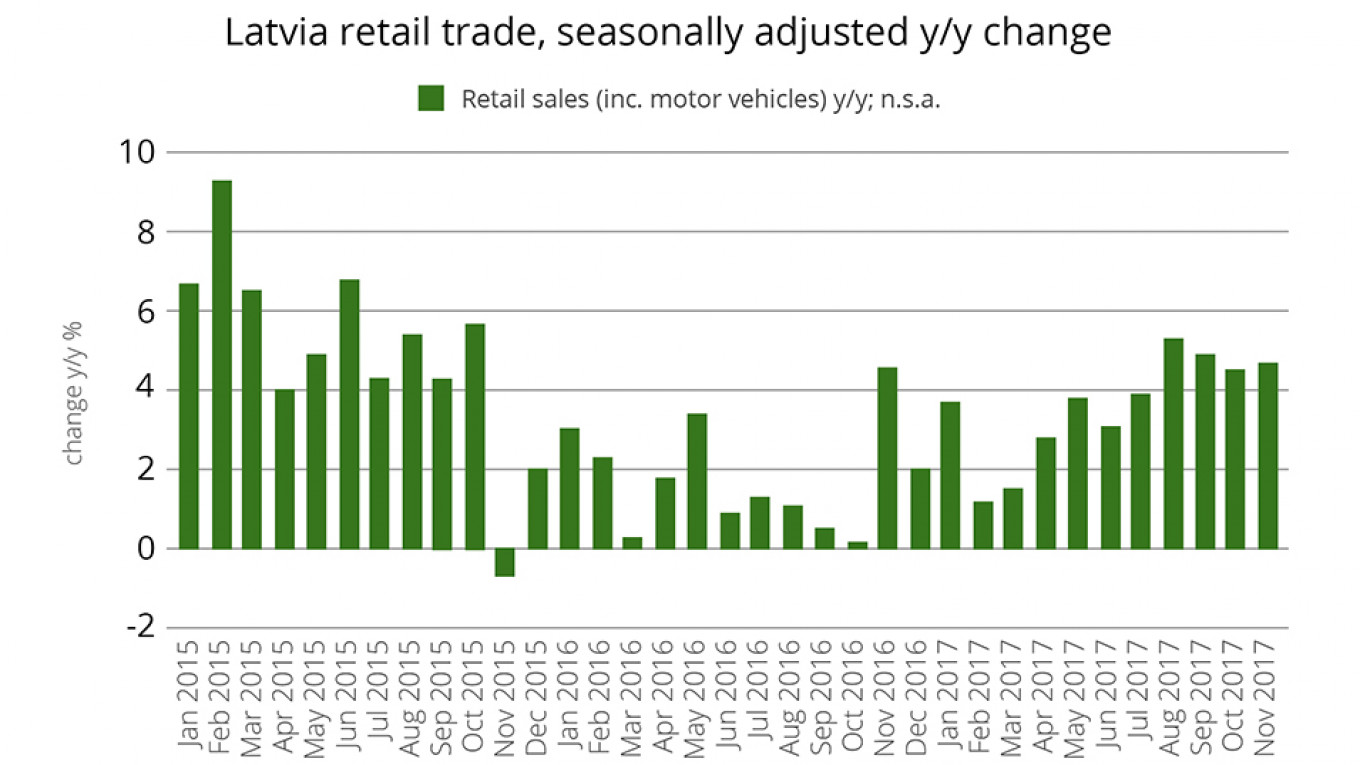

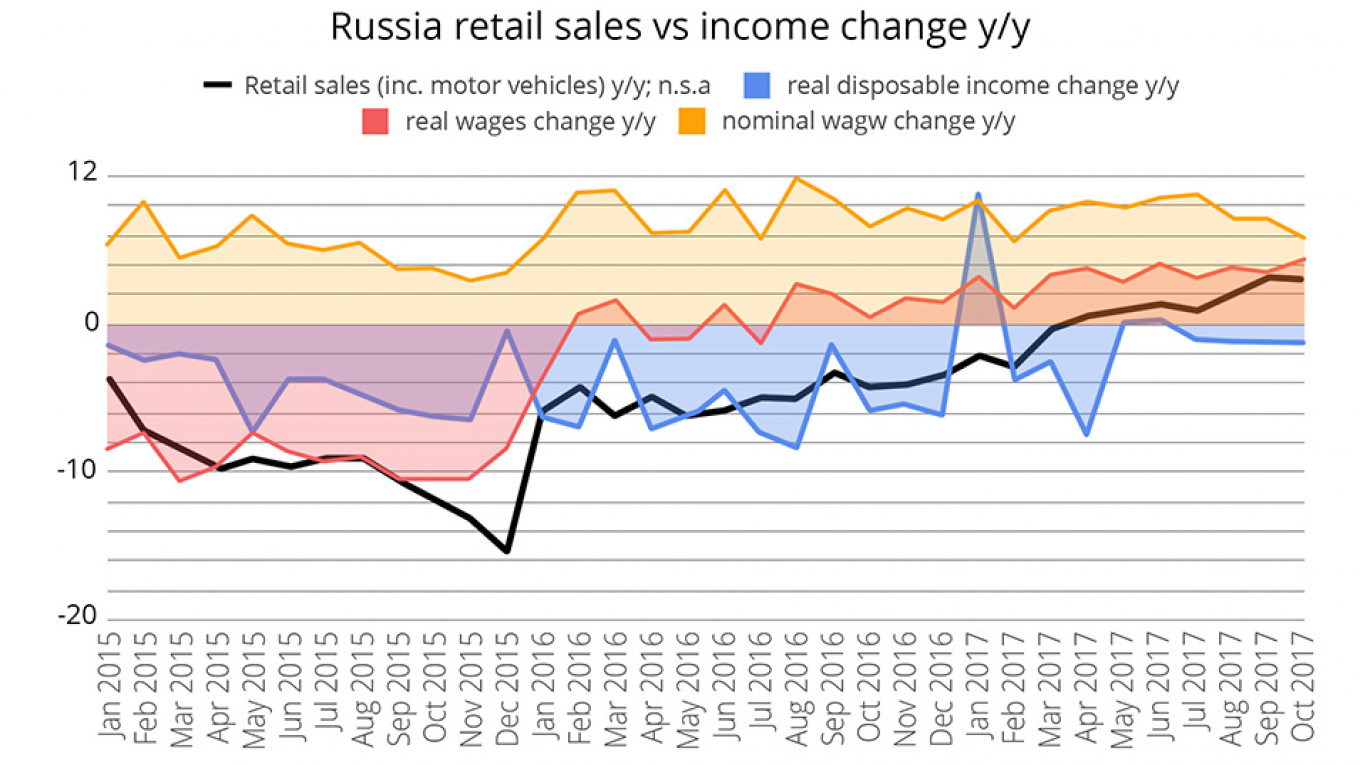

Real wages are rising and retail borrowing is growing at a double-digit rate. But after sharp falls in average incomes in 2015 and2016, consumers are more concerned with holding on to what they have than going shopping. The Watcom shopping index,which measures footfall in Moscow’s leading malls, is showing the worst year since its inception in 2014.

Companies are similarly cautious. Many are making money again as the economy revives, but political uncertainty and high interest rates on loans mean corporate borrowing fell through 2016 and has been essentially flat in 2017, keeping investment anaemic.

Both these issues are expected to diminish in 2018. A lower Central Bank interest rate should stimulate borrowing and spending. Middle-class Russians are starting to move upmarket in the food they buy, and the car market, which collapsed during the recession, has seen sales grow through most of 2017.

Addiction to oil

One of the biggest changes of 2017 is the health of government finances. Russia has gone a long way in breaking its addiction to oil and that takes a lot of pressure off the Kremlin in 2018.

The federal budget used to require an oil price above $100 a barrel to break even. After much financial engineering following the collapse of oil prices in 2014, the breakeven price has fallen to$70 and should reach $40 over the next couple of years.

In 2016 the situation was so bad that Moscow, unable to tap international capital markets because of sanctions, ended up borrowing money via a faux privatization of a stake in state-owned oil company Rosneft.

But the budget deficit in the first half of 2017 dropped to 1 percent from around 4 percent in the same period a year earlier and the Finance Ministry can now cover its borrowing needs in the domestic market, insulating it from the effect of sanctions.

Winners and losers

Growth is back, but on the ground the picture is mixed. The winners in 2017 included the steel sector, thanks to a recovery in international commodity prices, and agriculture, with a massive harvest of more than 130 million tons of grain breaking all Stakha-novite Soviet-era records.

Utilities have done well, with many companies completing investment programs, freeing up cash for dividends or other projects and making them a likely hit with investors in 2018.

Meanwhile, Russia’s biggest companies have used their deep pockets to buy out smaller rivals or drive them out of business through aggressive use of discounts and promotions.

The result is that while Russia’s overall economic growth is anaemic,at the corporate level, some companies, particularly in apolitical sectors such as retail and services, are doubling their revenues as they consolidate their position and focus on profitability.

In some more modern sectors, competition is becoming intense — something that will only benefit consumers. A price war between major mobile phone companies has broken out as rivals slash tariffs. The online taxi business has grown so fast and become so competitive that the cost of a ride has plunged.

Slower-moving industries are also starting to show signs of revival.Real estate was particularly hard-hit by the crisis, with completion of new office buildings in Moscow falling to the lowest in at least a decade, according to real estate broker JLL.

But the market may have reached the bottom. The construction slowdown will help create a shortage of large offices in the Moscow Central Business District and push rental rates up by as much as 25 percent by the end of 2019, says JLL. Vacancy rates are falling, which will only encourage developers to start new projects in 2018.

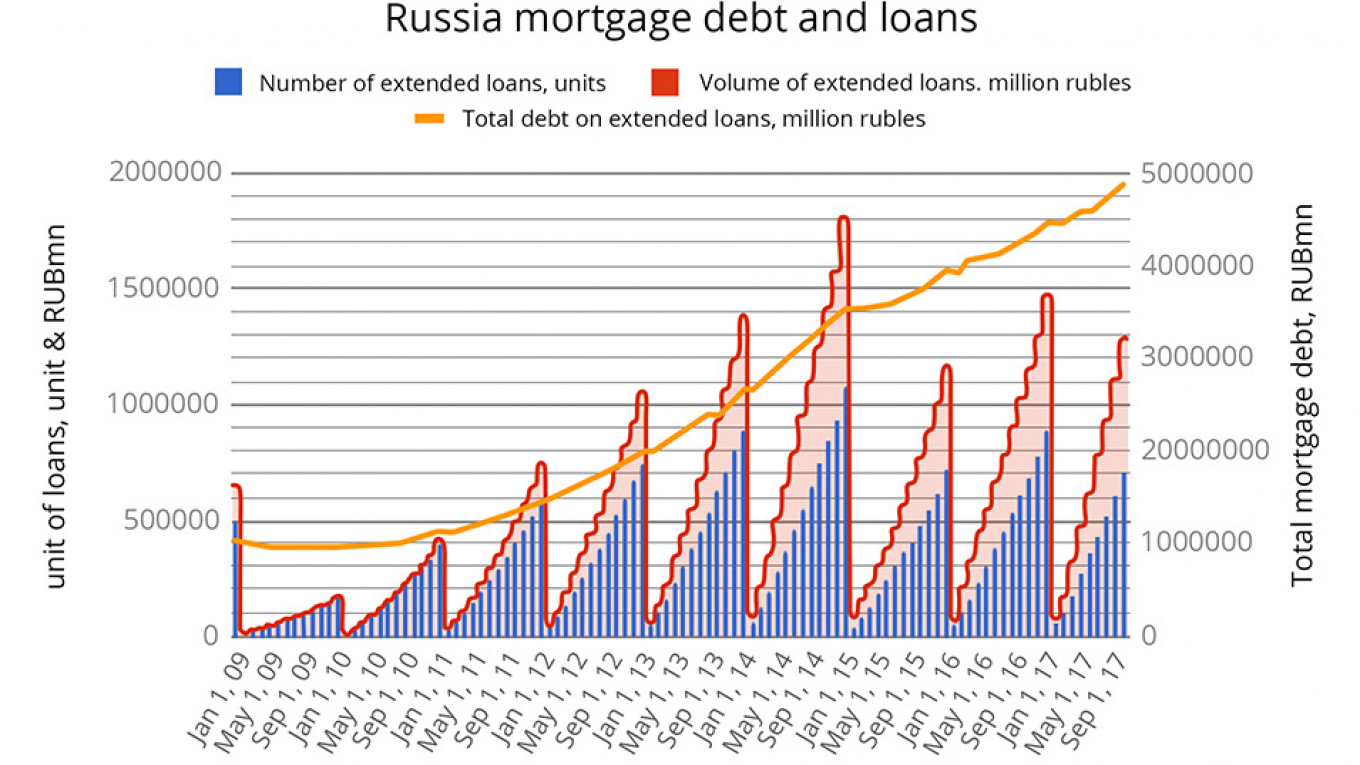

Residential construction is already doing well thanks to state mortgage subsidies and will only be boosted by falling interest rates.

Public vs private

Perhaps the best example of Russia’s mixed recovery is the banking sector, where private and state entities are in direct competition.

Lower interest rates and falling inflation have helped improve banks’ margins after a period of hell in 2014 and 2015.

But the big winner has been state-owned Sberbank, which in 2017 reported record quarterly profits and said it was targeting earnings of 1 trillion rubles ($17 billion) a year by the end of the decade — as much as the whole sector used to make in the boom years.

However, while Sberbank was on a roll, overall aggregate profits in the banking industry remained tiny and three large private lenders had to be bailed out by the Central Bank in 2017.

That is why Putin must reform the economy. In less political sectors companies are competing and growing. Where state-owned enterprises remain powerful they are a distortion and suppress the development of genuine businesses.

This could all change in 2018 with a real reform program, but that’s not likely.

Ben Aris is the founder and editor of Business New Europe.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.