To begin with, Levada regularly publishes three types of data on how Russians feel about President Vladimir Putin: popularity, trust and electoral ratings. Which data should we be looking at if we want to gauge Putin’s popularity?

First, I would avoid using the term “popularity rating.” There’s no such thing. The so-called electoral rating is an indication of how many people are willing to vote for a particular candidate. There is also the trust rating, which we compile by asking respondents to name five to six politicians whom they trust the most. Putin traditionally ranks first on that list.

Then, there are those who say they approve of Putin. That number is generally much higher than his electoral rating. That’s because the question of approval is quite a personal and emotional one. Whereas, when it comes to electoral ratings, people think: “Why would I go out and vote for someone who will win anyway?” The electoral rating is important, of course, but at the same time, it doesn’t reflect the actual number of supporters Putin has.

Voting requires action, whereas expressing support or approval doesn’t. Moreover, people know that their approval or disapproval won’t influence Putin’s behavior. Putin is unlikely to change his political course even if his approval rating goes down. We need to keep in mind that voters here feel they can’t influence politics through ratings.

From the Kremlin’s point of view, Putin’s approval rating helps him when it comes to foreign policy and communicating with other world leaders. It strengthens his position to be able to show his counterparts abroad that they’re dealing with someone who has the backing of the people, when they could only dream of similar approval ratings in their own countries. Strong approval could also work in his favor among the elite at home — but nothing more than that.

Keep in mind that Boris Yeltsin ruled the country with an approval rating of between 6 and 12 percent. He started off with figures similar to Putin’s but lost popularity while in office. It’s only natural for that to happen, whether you’re Donald Trump or Emmanuel Macron. In other countries, though, politicians risk losing the following elections. In our case, with the electoral system being controlled, Putin’s ratings are inconsequential.

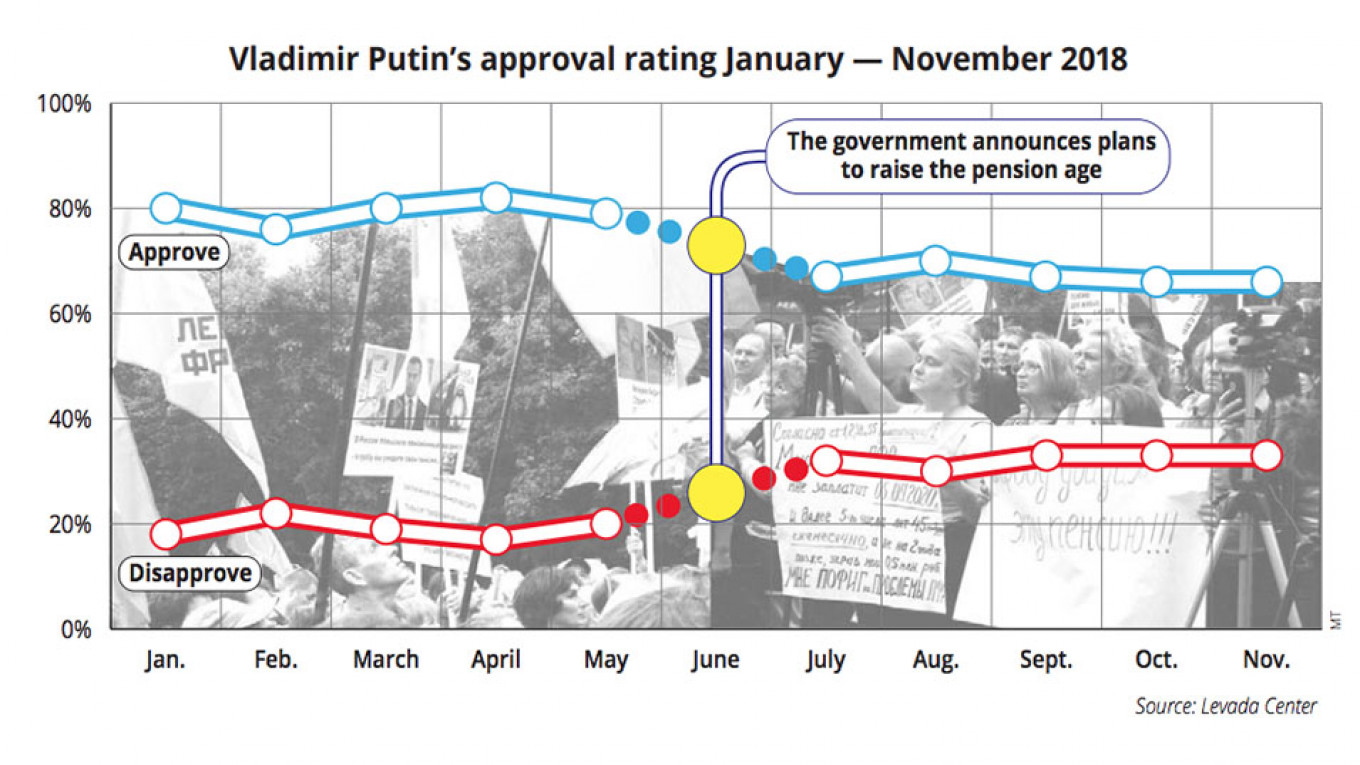

This year, Putin’s approval ratings plummeted to around 67 percent, which is about what it was before the annexation of Crimea. What happened?

I agree with those who argue that the slump is directly related to the increase in the pension age. Some sort of accumulated negativity toward Putin might also have played a part. A final factor is that people might be getting tired of the absence of any political alternative.

What is important to note, though, is that, after dropping to around 65 percent, it has remained there for about three months already. Still, 33 percent of respondents say they disapprove of Putin — that’s a lot, according to our standards.

In December 2011, some 36 percent of respondents said they didn’t approve of Putin. Within a year, by December 2012, it dropped to 35 percent and a year later it was 34 percent.

So we can say that the current disapproval figures are not the lowest ever, but they are definitely the lowest since the annexation of Crimea. In fact, his approval ratings had been rising gradually, until July 2018, when disapproval skyrocketed from 20 to 32 percent, which is a direct effect of the retirement age hike.

Is the effect of feelings of negativity over the pension age hike fading?

Our polls show that because of the pension law Putin lost the approval of about 15 million people. But the number stopped growing after July and has remained constant since then. Since the law has been passed and we don’t expect any new developments on that subject anytime soon, it’s not very likely that it will continue to affect Putin’s ratings.

Some have suggested that the clash with Ukraine in the Kerch Strait could give Putin’s ratings a bump, or even that it might have been orchestrated to that effect.

Of course the Kremlin will have thought through its actions and, although we don’t have any figures on that yet, we indeed expect it to have a certain positive effect.

Another recent poll shows that a record number of Russians, 61 percent, hold Putin responsible for the problems the country is currently facing. Is that unusual?

These results have attracted more attention than they actually deserve.

In that survey, respondents answered a two-part question on who was responsible for the country’s economic failures and, then, for the country’s economic successes. In both cases, the most common answer was “Putin.”

The news is that, for the first time, respondents pointed to Putin as being responsible for negative things, such as economic failures. Before, people would think that Putin had nothing to do with the country’s problems whatsoever. After the change to the pension age, it turned out that people were no longer willing to forgive him for such a controversial move.

But, in general, it shows that Russians think the president is responsible for everything that happens in the country — good and bad. So it would be wrong to conclude that people are finally holding him accountable.

Looking forward to 2019, what do you expect to happen to Putin’s ratings, taking into account a potential escalation of tensions with Ukraine? Can we expect a return to the high ratings of March 2014 or does Putin need another geopolitical victory for that?

That is unlikely. Even if we allow for the possibility of an escalation in Ukraine, I think it won’t have the same effect as Crimea had. There have been two peaks: First, during the Russian-Georgian War, and then Crimea. But it wasn’t the military victories that made Putin’s approval ratings skyrocket.

Rather, it’s the improved image of Russia in the eyes of those who like to think we are as powerful as the United States. Putin is seen as pursuing Russia’s interests and refusing to comply with the West.

There is a perception that the U.S. always does what it wants, ignoring the rules to achieve its goals, like it did in Kosovo, and that this is what defines a Great Power. To restore this status that the Soviet Union used to have was the dream of many ordinary and privileged Russians.

Putin has made people think Russia is powerful in a similar way, but they don’t care much about actual territorial victories. What we can predict is that the Kremlin, which is used to high ratings and obviously dissatisfied with the recent drop, will try to give them a boost. But it probably does not know itself how or when.

With all these disclaimers, what do Putin’s ratings tell us about Russia? Is there any point in following them so closely?

I think they are very symbolic: Ratings show how unified the population is. You can be happy with your life on a personal level, about your family life or your work. The next level is the state level, the way people feel about their country. So expressing approval for Putin as a president basically means saying, “I’m with you.”

The ratings are an imaginary space where people can come together and embody their country’s strength. But they don’t reflect Putin’s personal popularity. They show the absence of something else to be inspired by. In the absence of some sort of a spiritual leader who could unite people in Russia, Putin’s rating is high because people need a symbol that inspires, and Putin is one.

A version of this article appeared in our special "Russia in 2019" print issue. For more in the series, click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.