The 75th anniversary of the end of World War II was the only forthcoming event Russian President Vladimir Putin mentioned in his New Year’s address to the nation. Creating an alternative to the dominant Western narrative about that war is key to Putin’s way of securing Russia’s place in the world.

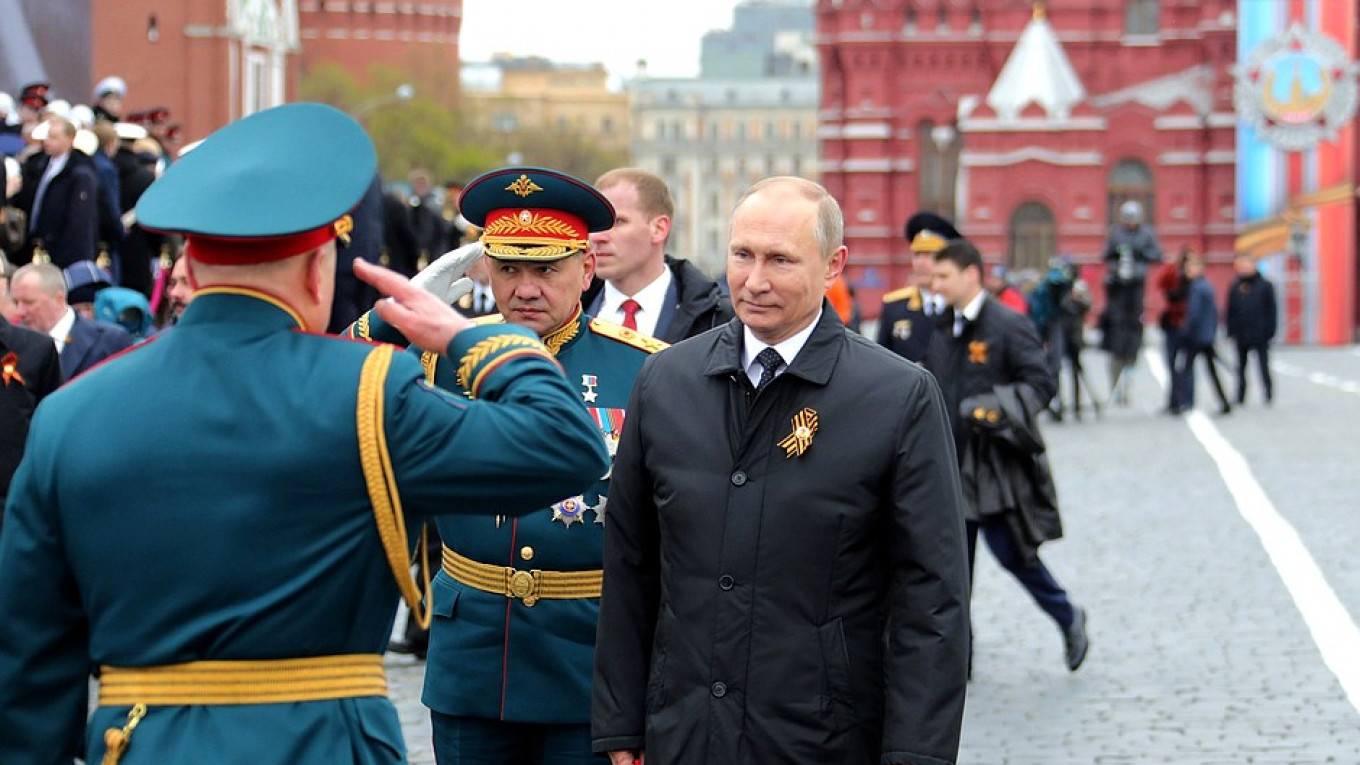

Putin has appeared lately to be obsessed with World War II, discoursing about it at every opportunity — during an informal session with other post-Soviet leaders, at his big end-of-year press conference, in a meeting with Russian tycoons, at the Defense Ministry in the presence of top generals. He’s talked time and again about delving into archival documents; he’s mentioned working on a scholarly article about the war. Even for a leader who has made the Soviet Union’s victory over the Nazis (seen by many as a triumph over a rotten Europe) a cornerstone of the new Russian national identity, Putin’s evident emotional involvement and the sheer time investment are unusual.

That’s because Putin, his foreign policy advisers and his propagandists see the dominant narrative of the war shifting against Russia.

Throughout the Cold War’s worst years, the victorious alliance of the Soviet Union, the U.S., the U.K. and France was a reminder that cooperation was possible. There is, however, a tendency to dump that baggage now and to treat Russia as a villain without any qualifications. Late last year, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson was asked to recall when he’d changed his mind. His response:

What I’ve really changed my mind on was whether it is possible to reset with Russia. I really thought, as I think many foreign secretaries and prime ministers have thought before, that we could start again with Russia. That it’s a great country we fought with against fascism. It was very, very disappointing that I was wrong.

The Kremlin is extremely sensitive to such signals — not just for domestic propaganda reasons, but because Russia’s global power is still based on some important spoils of World War II. As one of the nations that vanquished Hitler, the Soviet Union didn’t just win control over Eastern Europe, it received a place atop the postwar global order and an all-important permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. If the Soviet Union is primarily seen as Hitler’s ally at the outset of the war — which of course it was — rather than a Hitler conqueror at its conclusion, if Russia has never really been on the right side of history, it has no claim to moral authority and to a role as a global arbiter. To Putin, that role is, in a way, as important as Russia’s nuclear shield. The ability to say authoritatively what’s right and what’s wrong is, after all, a major part of what makes the U.S. a global superpower.

Kremlin-linked historians and propagandists see the shifting narrative as the result of Eastern Europe’s increased role in the continent as a whole. Since, of all European nations, Poland and the Baltic states are the most concerned with the policy and politics of memory, their loud voices have drawn the European political elite’s attention away from the victory and toward the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939, in which Nazi Germany and Josef Stalin’s USSR divided up spheres of influence in Europe. One result of this was a European Parliament resolution last year that equates the Soviet regime with the Nazi one in terms of the damage done to Europe, a document that has been a strong irritant to the Russian leadership and to Putin personally.

This year’s first issue of Russia in Global Politics, a foreign-policy journal with strong Kremlin links that often provides insights into the Putin administration’s geopolitical thinking, contains the transcript of a fascinating debate among prominent Russian historians on how Russia might try to shape the World War II narrative in a more politically advantageous direction. The debate casts Israel as Russia’s only ally in fighting the turning tide, and Poland as its main adversary.

The logic behind this is that Israel will never agree with the propaganda narratives of the nationalist governments in Poland and the Baltics, which aim to reject all blame for locals’ cooperation with the Nazis during the Holocaust. Indeed, as the Polish government has doubled down on its own nationalist memory policy — which casts Poland as an innocent victim of both Russian and German aggression — it has clashed repeatedly with Israel and the global Jewish community.

The Poles have also had their difficulties with the European Union: They’ve tried to push through a reform of their judiciary that is seen in Brussels as an attack on the rule of law, and they’ve torpedoed various common policies in areas such as immigration and climate protection.

So here’s the recipe for the Russian memory counteroffensive as formulated during the discussion by Moscow State University historian Fyodor Gaida:

So then our main scapegoat is Poland. If we and the European bureaucrats need a common enemy, I guess Poland will be the first candidate. Poland’s role should get the most attention, which is what’s happening today. Our main ally is, yes, Israel. I agree completely, this topic must be developed: Jews in the Red Army and so on.

Gaida also proposes that Russia should stress that all former Soviet republics contributed to the victory, rather than that Russia led the effort.

So far, Putin has played all these cards. He has repeatedly recalled Poland’s land-grab in Czechoslovakia after France and Britain agreed to that country’s carve-up in Munich in 1938. During the meeting with the generals, he recalled how a Polish ambassador to the Third Reich told Hitler he’d be commemorated with a statue in Warsaw if he managed to dispatch the Jews to Africa, as he once planned. “A bastard, an anti-Semitic pig, I have no other way to say it,” Putin raged.

Never mind that the ambassador in question, Josef Lipski, actually helped Jews fleeing Germany before the war get into Poland, as Polish Jewish community leaders pointed out. On Jan. 23, Putin will give an address at a ceremony in Israel commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Red Army’s liberation of Auschwitz, but Polish President Andrzej Duda has refused to go because he hasn’t been given a chance to speak.

As for the former Soviet republics’ role in the victory, Putin made it the focus of his meetings with ex-Soviet leaders last month, telling them, “For all of us — I’d like to stress that and I know you agree — for all of us this is a special anniversary, because our ancestors, our fathers, our grandfathers have placed so much on the altar of our then-common Fatherland.”

Over the next few months, we should expect the Russian memory counterattack to develop in new directions. During the historians’ debate, Alexander Lomanov from the International Economics and Foreign Relations Institute in Moscow proposed working more closely with China, which, he said, would appreciate more attention to its role in defeating Japan and thus allowing the Soviet Union to spare its forces for the anti-Hitler front. In return, he said, China would be happy to promote the idea that the Soviets were the main force behind the victory in Europe:

The Chinese narrative has retained many of the familiar positive images of the “great Soviet Union” and “mighty Red Army,” which made the decisive contribution into crushing fascism. Given the strict control over historical memory in China, any “spontaneous” criticism of the Soviet Union role in World War II is impossible. The narrative is created from above and controlled by the political elite.

Much of Putin’s foreign-policy activity this year will be directed toward trying to rebuild a more Russia-centric concept of the victory over the Nazis. This is territory where Putin isn’t prepared to give ground, and given the enormous complexity of the historical material as well as the cross-currents of Israeli, U.S. and European memory politics, he can put up quite a diplomatic and propaganda fight.

It's precisely these complexities, though, that make any kind of government involvement in shaping the memory of World War II so abhorrent. As politicians cherry-pick the blood-soaked record for political purposes, truth is the biggest loser. As Alexey I. Miller of the European University in St. Petersburg put it during the historians’ discussion, “The idea that we are returning to historical memory to overcome political differences and enmity has been superseded by the understanding of memory as one more area where political goals are being sought.” Russia, given its size and the dizzying extremes of its World War II record, shouldn’t get involved in this. It should take pains to recognize and atone for its crimes even as it celebrates its heroic past. Even if narrative wars are a reality, refusing to fight them is the strongest possible position.

This article was first published by Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.