Russia’s pact with OPEC has significantly enhanced President Vladimir Putin’s presence on the world stage, but as his geopolitical clout keeps growing the economic benefits for his country have lost some potency.

What began in 2016 as a temporary measure to boost oil prices has become an alliance meant to last for “eternity.” For a third year, Russian companies are curbing output and scaling back investment in new projects. Yet concerns about how this is starting to weigh on the nation’s growth are overshadowed by the benefits to their president’s international profile.

After years of Saudi Arabia calling the shots within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Putin has quickly stolen the limelight. At the Group of 20 meeting in June, he demonstrated his new power over the global oil market by announcing an extension of production cuts himself, essentially making the group’s mid-year talks in Vienna redundant.

Putin will deliver the keynote speech at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Russia on Thursday, and oil traders will be watching. The president’s comments on the market have become “deeper, much better researched and more influential,” said Ildar Davletshin, an analyst at Wood & Co.

“Putin managed to strengthen his influence in the Middle East and build up a relationship with Saudi Arabia,” said Dmitry Marinchenko, a senior director at Fitch Ratings Ltd. Still, the OPEC+ deal hasn’t delivered the promised inflow of investment from Russia’s new Middle East allies, he said.

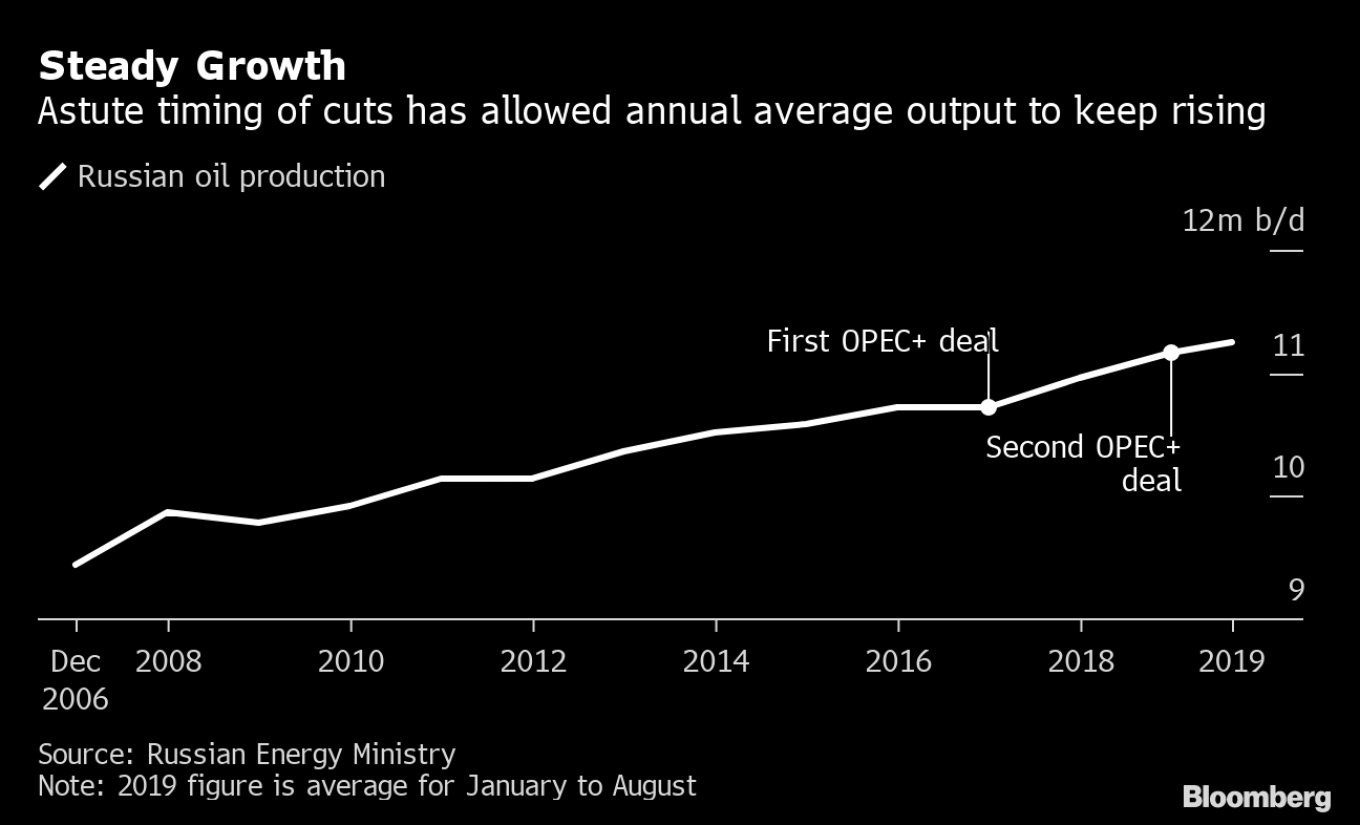

To be sure, the price gains that resulted from the so-called OPEC+ deal have benefited Russia. Putin and his Energy Minister Alexander Novak have also managed their cooperation with the group astutely, bearing a smaller share of the cuts than Saudi Arabia despite having higher production, and timing the curbs in such a way that Russia’s average annual has continued its decade-long ascent uninterrupted.

Before the first OPEC+ deal in late 2016, then again ahead of the second round of curbs agreed on in December, Russia hiked oil output to post-Soviet records, setting a generous baseline for its cuts. In both cases, the country was given several months to reduce production in line with its quota, and frequently left it drift above that level, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The initial OPEC+ deal reached in late 2016 ended a slump in Brent crude prices, which fell as low as $28 per barrel at the start of the year. By mid-2018, extensions of the deal helped push the prices up to $80 a barrel, earning Twitter rebukes from U.S. President Donald Trump but helping Russia’s government run the widest budget surplus in a decade.

“Back then it made economic sense for OPEC and Russia to agree on production targets, now not so much,” Goldman Sachs economist Clemens Grafe. “Having these extended periods of caps on production do not make much sense, this just gives producers who are not bound by the agreement time to increase their market share.”

The price effects of the more recent deals were more modest, with crude averaging below $60 on concerns of slowing demand growth due to the U.S.-China trade war. While that limits the benefit of Russia’s cooperation with OPEC, it’s likely that crude would be even lower if producers were to end their agreement and open the taps.

The latest cuts, which run until the end of the first quarter next year, take as much as half a percentage point off Russia’s annual growth, which is a significant impact given that the economy expanded 2% on average in the past two years, said Grafe.

Throughout the OPEC+ agreement, the benefits of higher oil prices to the wider economy has been minimal since the Finance Ministry is stashing away all additional revenue into a wealth fund, Grafe said. Russia imposed a budget rule in 2017 saying all energy revenues coming from an oil price above $40 should be saved, boosting the fund to $123 billion from about $70 billion in late 2016.

Middle East ties

Russia’s oil companies curbed spending on new projects and overall investment in the economy will expand 2% in 2019, half the pace of last year, according to the official state forecast. Still, many of those companies are generating enough cash to pay out handsome dividends, offering higher total returns to shareholders than most of their international peers, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Russia’s largest oil producer Rosneft PJSC said the nation may lose out to U.S. shale producers if the deal is extended, while Finance Minister Anton Siluanov called for considering all economic consequences of the new agreement. Even so, Putin’s drive to strengthen ties with Saudi Arabia and gain geopolitical weight in the Middle East silenced doubts over the viability of OPEC+ cooperation. The president’s agreement in June to keep Russia’s oil production flat for another nine months met no resistance.

During Soviet times, the Kremlin’s aim of spreading communism limited who wanted to do business with it in the Middle East, said Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist at the Institute of International Finance in Washington. Putin’s less ideological, more businesslike approach is winning Russia more partners than ever there, she said.

That new reality will be on show next week, when Novak meets with fellow OPEC+ ministers in Abu Dhabi, underscoring Russia’s political and economic importance to the region.

“OPEC is more important for Russia’s geopolitics than the economy,” said Ribakova. “This is a big club of oil producers and it is important for Russia to be a part of it, and have its say.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.