Last year, Yelena Rydkina was working in Moscow’s biotechnology industry when she decided to get several friends together to organize a popular science conference on sexuality.

“I saw that we have a lot of trouble with sex education here, that people aren’t open about sexuality, and I wanted to change that,” she said.

The conference — which covered topics ranging from the biology of sex to queer culture to kink — was a labor of love for Rydkina, and she doubted that there would be much public interest. But over 350 people showed up, despite the fact that the conference had little advertising besides its website. Soon, Rydkina had quit her job in biotech.

Today, she works as a “sex evangelist” for Pure, a mobile app for “anonymous discreet dating” on the Russian market. She lectures on sex, writes blogs and articles, and records educational videos. Her most recent project, Pure.School, is a series of online sex education courses. In Silicon Valley, Rydkina’s story would hardly be surprising. But, in Russia, it comes at a time when the government is increasingly taking aim at the Internet in its campaign to promote “traditional values.”

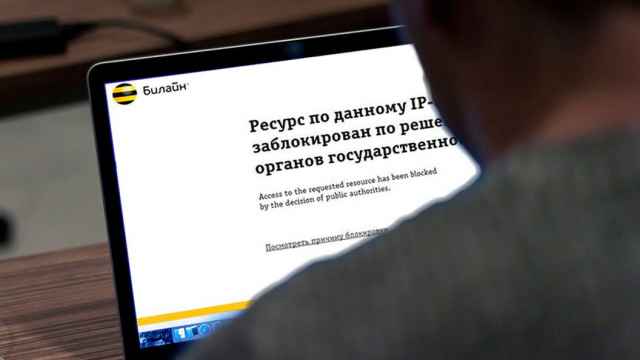

This month Russian media watchdog Roskomnadzor blocked Pornhub and YouPorn, two of the world’s most popular pornography sites. When Pornhub set up a mirror site to allow Russian users access, that too was blocked. Next, Roskomnadzor blocked Bluesystem.ru, one of the country’s top gay news and dating portals.

If blocking pornographic and sexual Internet content may seem superficial in the broader scope of censorship, it has greater meaning in Russia. For years, the Internet has been a largely free space in an otherwise state-controlled media environment. And as the Kremlin pushes socially conservative values, the web has also served as a place where people can enjoy those sexual identities and practices not supported by the government.

For this reason, “information technology can be considered a threat to traditional values,” says Gregory Asmolov, a researcher on mass communications at the London School of Economics, who has lectured at a conference organized by Rydkina.

Sexual Revolution

Russia has a complicated history with sex and the media. From the Stalinist period onward, Soviet culture promoted social conservatism and the word “sex” was often synonymous with vulgarity. Open discussions or depictions of sex were largely absent from official Soviet culture, and pornography was a rarity.

But with the arrival of perestroika and the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, the restrictions disappeared. Foreign pornography streamed into Russia, where it was displayed and sold openly. Sexuality returned to popular culture, and sex scenes — often graphic and violent — became a hallmark of Russian filmmaking in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1993, but few truly progressive attitudes toward sex emerged.

For many Russians, the influx of pornography and garish sexuality was a trauma that went hand-in-hand with the social and economic upheavals of the 1990s, says Eliot Borenstein, a New York University professor who has extensively studied sexuality in modern Russia. “For years, the Soviets had presented a nightmarish vision of how low [American] culture was,” he says. For many, the wave of porn “showed how bad it really was.”

Changing Rules

Pornography has largely disappeared from magazine racks since a 1996 law greatly restricted its sale. And with the arrival of the Internet, much of it went online.

But with the government’s passage of a 2013 law criminalizing “homosexual propaganda” and the increasing focus on family values in Russia, sexuality online has gradually found itself in the legal system’s crosshairs.

Since 2014, Yelena Klimova, the creator of Deti-404 (Children-404), a distinctly non-sexual website providing support for LGBT teenagers, has repeatedly found herself facing charges for spreading “gay propaganda” among minors. In January 2015, she was fined for the offense, but the fine was later cancelled and the case returned to a lower court when she presented the analysis of a Roskomnadzor-accredited expert who did not find “gay propaganda” in her actions. But the lower court reimposed the fine.

And in September 2015, Roskomnadzor blocked the Deti-404 page in the VKontakte social network after a regional court ruled that it promoted non-traditional sexual relations among minors. Deti-404 subsequently created a new VKontakte page.

The blocking of Pornhub and YouPorn stemmed from a similar ruling in 2015, when a regional court determined that the content violated a 2010 law protecting children from information dangerous to their health and development. The blocking of Bluesystem.ru follows a regional judgment, although it is not clear what law the portal violates.

Rydkina says that the official push for conservatism worries her, but, so far, she doesn’t see any major obstacles to her work.

This is not surprising, says researcher Asmolov. While these bans are concerning, they are decentralized, resulting from the rulings of specific judges. On the whole, Russia remains less restrictive than many other countries. Large numbers of similar websites continue to function online, and Russia is unlikely to ban all pornographic sites or all sites dealing with LGBT issues.

In fact, days after being banned, Bluesystem was available from a different domain and Pornhub opened an account in VKontakte. “That’s what really highlights this contradiction: When a banned site like Pornhub is allowed to promote its content on a Russian platform,” says Asmolov.

Changing Values

Contradiction is central to Russian attitudes toward sex. Public opinion surveys regularly show that Russians support censorship of sexuality in media. But people’s sexual lives are hardly conservative.

Some might call this hypocrisy. But Marianna Muravyova, a sociologist at the Higher School of Economics, suggests that it is pragmatism, and that — with the exception of views on homosexuality, which remains taboo — the conservatism advocated by the Kremlin has a low following in Russia.

“People may claim they support traditional values,” Muravyova says, “but if you look at their attitudes toward sex outside marriage, living together outside of marriage, illegitimate children and abortion, a very liberal picture emerges.”

Even Rydkina, who says she has witnessed the effects of state television on her own parents, remains guardedly optimistic. While helping her friends organize porn-themed parties in Moscow, she began to notice that otherwise straight-laced acquaintances were showing up at these get-togethers.

“I believe people in Russia are too constricted internally,” she says. “There’s a lot of pent-up kinky energy here.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.