If it comes to it, Russian Internet pioneer Anton Nossik will accept imprisonment, but he won’t do so unprepared.

A day before meeting at a central Moscow café, he read three books from cover to cover in a single day.

The reading list, mixing fiction and non-fiction, is grim: “Hostage” by former Yukos manager Vladimir Pereverzin, Andrei Rubanov’s “Do Time Get Time” and a memoir by Grigory Pasko, a military journalist once jailed on treason charges — all writings on life in a Russian prison.

“I'm expanding my horizons. The knowledge I’ve gained in the past months far exceeds anything I've learned in the previous decade,” Nossik says drily in a thoughtful baritone, while sipping an orange juice.

Nossik is widely known as one of the founders of the RuNet. In 1997, he returned to Russia after several years in his second homeland Israel, and plunged headfirst into Russia’s fledgling tech scene. Name the outlet — Lenta.ru, Gazeta.ru, Newsru.com, Rambler — and Nossik is likely to have had a hand in it as a founder, editor or media manager.

For decades, he has also been a prolific blogger of cutting commentaries that spare no one, least of all the Kremlin. But after hundreds of critical posts, ironically it is a pro-government opinion piece that could now land him in jail.

In a blog post written in October 2015 entitled “Erase Syria From the Face of the Earth,” Nossik welcomed Russian airstrikes on Syria, which, according to the Kremlin, were exclusively targeting Islamic State terrorists. Nossik, who wears his heritage in a yarmulke on his head, didn’t care for caveats. He argued civilian deaths were an acceptable price to pay for the annihilation of a country he compared to Nazi Germany.

He repeated that view during a broadcast on liberal radio station Ekho Moskvy later that day, saying he welcomed Russian raids on women, children and the elderly because “they are Syrians. They’re a threat to Israel.”

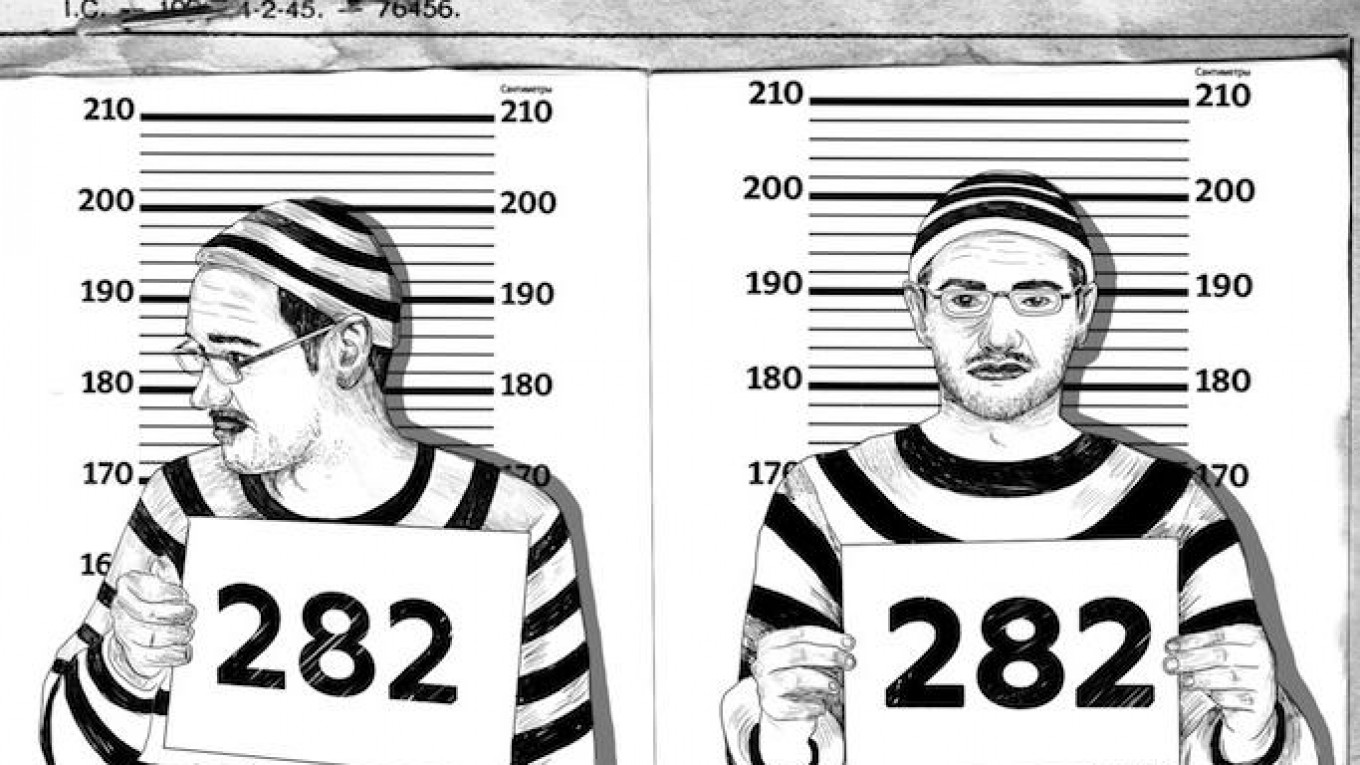

Many in Nossik’s own circles condemned the post. But few thought his views deserved time behind bars, which is exactly what prosecutors are now demanding. They accuse Nossik of violating Article 282 of the Criminal Code on hate speech.

The law, which has been a favorite target of Nossik’s own writings, covers public statements “inciting hatred or hostility, or humiliation on the basis of membership of a social group.” It carries a penalty ranging from a fine to a four-year prison sentence.

The infamous Article 282 has served to prosecute a plethora of social groups: ranging from hard-core nationalists to jihadists. Increasingly, it is also used to target lone individuals expressing opinions seen as radical or showing support for such views. Article 282 is frequently paired with the equally infamous Article 280, against “separatism.”

In one prominent case, an electrician from Tver, Andrei Bubeyev, was sentenced to years in prison earlier this year for sharing an illustration of a tricolor toothpaste tube with the text “Squeeze Russia out of yourself.” The social media post was written in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and involvement in Ukraine.

“This law shouldn't exist,” says Sergei Badamshin, Nossik's lawyer. “It's being used in a fight against those who think differently and it’s being abused by law enforcement.”

And yet it’s becoming increasingly popular. According to figures

gathered by the Sova human rights group, there has been an explosion

in hate speech convictions — from 47 in 2007, to 165 in 2014 and

232 cases last year. For the past two years, 84 percent of cases

concerned opinions expressed online, sometimes by just liking or

sharing a post on social media.

According to Alexander Verkhovsky, director of Sova, the problem is not as much with the legislation itself. In fact, the Russian law mirrors hate speech legislation found in many European countries. But it is frequently misused by law enforcement to boost crime quotas. “They're being led by statistics,” says Verkhovsky. “It's much easier to fight ‘terrorism’ by sifting through VKontakte than to hunt people down on the streets.”

And where lazy law enforcement officials fail, overzealous Russians are often willing to lend a hand. Nossik’s case ended up on the prosecutor’s desk after a journalist working for state media filed a complaint. “Report thy neighbor to the authorities is a very well-known Russian sport,” says Nossik, deadpan.

The person who filed the complaint, Ilya Remeslov, begs to differ. He says he is acting to preserve societal harmony. He’s done it before; Remeslov was also involved in initiating a case against political analyst Andrei Piontkovsky, after he wrote an article commenting on the hypothetical secession of the North Caucasus republic of Chechnya.

“It’s part of my community work,” says Remeslov, stressing he doesn’t receive any state funding. He wouldn’t want to see Nossik behind bars. “It would make a political prisoner out of someone who isn’t,” he says. “A hefty fine” will do.

Nossik, however, will not be muted. The threat of prison has not made him any more guarded in his views. “Either you go out and protect Syrian children from Russian bombs or you accept responsibility for their deaths,” he says. “People delude themselves and if there is any value in what I do, it is to rid people of their delusions. I hate hypocrisy.”

Besides, his supporters argue, his opinion on Syria is unlikely to have incited any action. “If Putin had started bombing Syria as a result of this statement it would have been a different case and we could call Nossik the most influential blogger in the country!” his lawyer jokes.

Then again, Nossik admits that his outspoken commentary has long put him in the crosshairs. “I’m surprised it took this long,” he says. “If you stick out, regardless of whether you praise or blame Putin, you’re at risk.”

He could easily flee Russia, as Piontkovsky did. But Nossik has a wife, a son and a mother in Russia. “As long as they’re not ready to leave, I’m not leaving either,” he says. Besides, he argues, the widely covered case has given him a new platform from which to spout his views on Syria and Article 282. “This court is my instrument,” he says.

On Oct. 3, a Moscow court will decide whether Nossik will walk free, be forced to do correctional work or be jailed. “A fine is the easiest, jail the loudest and acquittal is the most just,” says Nossik.

He won’t, however, be tricked into picking a favorite. “I’ve

been warning about this law in my blogs for years. So if I am jailed,

then that just proves me right,” he says, smiling.

“There's nothing shameful in being right.”

The Islamic State is a terrorist organization banned in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.