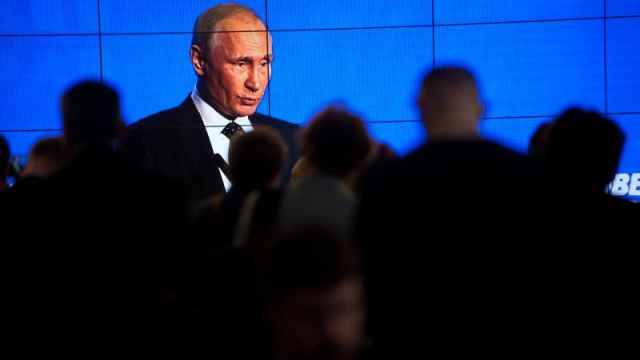

Ahead of Russia’s presidential elections in March, slated to give President Vladimir Putin his fourth term, Russian political commentators are updating their power maps of the country’s elite.

Yevgeny Minchenko’s Politburo 2.0 analysis is the most widely reported so far. It ranks the country’s top officials, heads of state corporations and oligarchs under the Russian president according to their influence.

One of the country’s top political journalists, Konstantin Gaaze, then proposed his own model of the Russian leadership: An informal court of Putin’s personal friends-turned-billionaires and confidants superimposes onto official government and adds more levers to the Russian president’s policy tool kit.

While these schemes are often well-researched and fun to read, their practical use for explaining — much less for predicting — the leadership’s moves is limited.

As an example, let’s take the scandal over Siemens’ claims that its turbines were delivered to Crimea in violation of EU and U.S. sanctions on Russia. International businesses in Russia are closely following the case because its outcome will likely impact the country’s investment climate in a big way.

Analysts and observers still do not know — nor can this style of political punditry tell us — whether any lessons are being learned from this situation and, if so, what the lessons would be.

We have no idea on which level this crisis is being handled by the Russian side. Is it at the level of the heads of subsidiaries of state corporation Rostec, which were involved in building an electricity station in Crimea? Or is it at the level of Rostec’s leadership? Or of government ministers? The presidential administration? President Putin himself?

What motivates such decisions? Anti-Western sentiment, concerns over the short-term interests of the state or of the broader economy in the long-term? Personal ambitions? Corporate interests? Most probably, it will be a cocktail of all these factors and more. But then which is most important?

If something similar happens with another huge international company, who will be making decisions on the Russian side on how to proceed? If, as is likely, it is the president, then who will provide him with the facts and expertise to inform his decisions?

None of the hyped rankings of Russia’s political elite are much help in answering these questions, which are arguably more relevant than which CEO of a certain state corporation has dropped a notch down the ladder or which oligarchs have edged a centimeter closer to Putin.

If anything, it seems to have become more difficult to answer questions about the Kremlin’s decision-making vertical 18 years since Vladimir Putin shot to power.

Years ago, when I was a political reporter and, for a while, a member of the Kremlin’s journalist pool, the division of functions and the level of authority of people in Putin’s retinue appeared quite clear.

Alexei Kudrin was finances supremo. German Gref was responsible for economic development. Dmitry Kozak was Putin’s crisis manager. Igor Sechin managed Putin’s protocol.

Maybe this could be explained by a handful of confidants Putin brought with him from his previous jobs and to whom he gave broad authority to push economic reforms during his first term in power.

This delineation became blurred after the 2003-2004 Yukos case demonstrated the growing role that the so-called siloviki — officials with connections to law enforcement— wanted to play in the Russian economy.

Putin’s role as prime minister in 2008 and his newly found taste for managing massive economic challenges resulted in a further confusion of political and economic functions among his entourage.

This period saw the rise of new, influential business players close to the president and the development of state corporations that combined government and business mandates while their powerful heads actively engaged in political lobbying.

Years later, we are still no clearer in understanding how this official decision-making mish-mash works in any specific case.

Several months ago my employer, a business consultancy, received a request from a client, a global industrial conglomerate, to assess the risks of partnering with a major Russian state corporation.

In addition to a customary due diligence report and an organizational power map, the client wanted answers to questions, like: “Who do we talk to in the target company if we are prepared to spend $1 billion? Will it be the same person if we invest $10 billion? Who in the Russian government and the presidential administration will have the decisive vote on a potential investment of this size? If we decide to disengage from the target company, who will be the people inside the corporation and outside it who we would need to talk to? Who will make decisions if it a conflict emerges?”

This was a vivid example of how some foreign investors worry that decision-making in Russia deviates significantly from the organization’s official structure or hierarchy.

Getting information about the Russian government and, more generally, official decision-making is more difficult than building influence ratings and organizational charts.

But with what is at stake for foreign governments and businesses operating in Russia, both foreign and local, it is one of the few reliable methods to mitigate business risks.

Nabi Abdullaev is an Associate Director at Control Risks and a former editor-in-chief of The Moscow Times.

The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.