GROZNY, Russia — In 2015, Ramzan Kadyrov, the feared head of Russia’s Republic of Chechnya, decided to make a movie. In Chechnya, that might seem like a far-fetched idea. Then, the republic had only two movie theaters for a population of 1.4 million. There is no local filmmaking tradition whatsoever. So Kadyrov turned to Beslan Terekbayev. Soon, Terekbayev’s ChechenFilm studio had produced “Whoever Doesn’t Understand Will Get It,” an action movie starring the Chechen strongman himself.

The film has never been released publicly, but Kadyrov did publish a few clips to his famous Instagram account. One shows him surrounded by military vehicles firing a machine gun into the air. Another depicts him meeting an actress dressed as Great Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II.

On the surface, “Whoever Doesn’t Understand” may simply seem like the Chechen leader’s vanity project — but Terekbayev and ChechenFilm are no joke. “Whoever Doesn’t Understand Will Get It” was later used by Kadyrov in real life as a slogan with which to threaten members of Russia’s liberal opposition. With Kadyrov’s backing, Terekbayev intends to turn the Muslim-majority North Caucasus republic into a filmmaking powerhouse — and he sees his work as a direct challenge to the liberated values promoted by Hollywood.

Against the odds

Widely accused of human rights abuses and murdering his political opponents over nearly a decade ruling Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov is also known for his love of film. In the past, he has organized visits to Grozny for movie stars including Elizabeth Hurley and Jean-Claude Van Damme.

With Kadyrov’s support, ChechenFilm is building a cinematic infrastructure where none has ever existed. Besides Kadyrov’s action film, the studio is currently producing five major feature films, has begun a Chechen-language television series and has opened two new cinemas and has set-up a cinema school in Grozny.

At recent auditions for an Russian-Indian co-production called “Best Friends” 13-year-old Rayava Chebukhanova had picked a famous poem by Russian Alexander Pushkin to recite to camera. At the beginning she was struggling with shyness, she was in tears by the end. Even though the Chebukhanov family — like many other local families — had rarely visited the cinema, Rayava’s mother and brother auditioned for a role in the same production on the same day. “We have a lot of talented children…” said Khava Chebukhanova, Rayava’s mother, “[but] it is well known that they have nowhere to channel their talents.”

In these conditions, cultivating a cinema-going culture has been an uphill struggle. Terekbayev, who was director of the first cinema to be opened in Chechnya in 2008, said financing for their projects is mostly raised from private Chechen investors. While Hollywood is content to spend tens of millions of dollars on a feature film, Terekbayev is focused on low-budget films that can be made for under 70 million rubles ($1.1 million).

The company’s new cinema school, Step, is headed by Tatyana Boika, a 23-year old art academy graduate. With few specialists on hand, Step imports instructors to teach six-month introductory courses on acting, directing, producing and operating. A lack of equipment and film specialists also means the editing of ChechenFilm’s productions is outsourced to Moscow or St. Petersburg, Terekbayev said.

One of ChechenFilm’s biggest stars is 23-year-old Dzhamalaila Selikhanov. Selikhanov who is currently playing the lead role in the upcoming action film “Clash,” which tells the story of a wounded Chechen special forces officer and his quest to avenge the death of his sister in a mountain village. Selikhanov was spotted by ChechenFilm producers while traveling home from university, and gave up a job at a bank to take part in his first shoot.

Selikhanov, who is also considering a career as a martial arts fighter, said in an interview that an acting course at Step had helped him hone his skills. “Before that I used to go red in front of the camera,” he said.

One Man Show

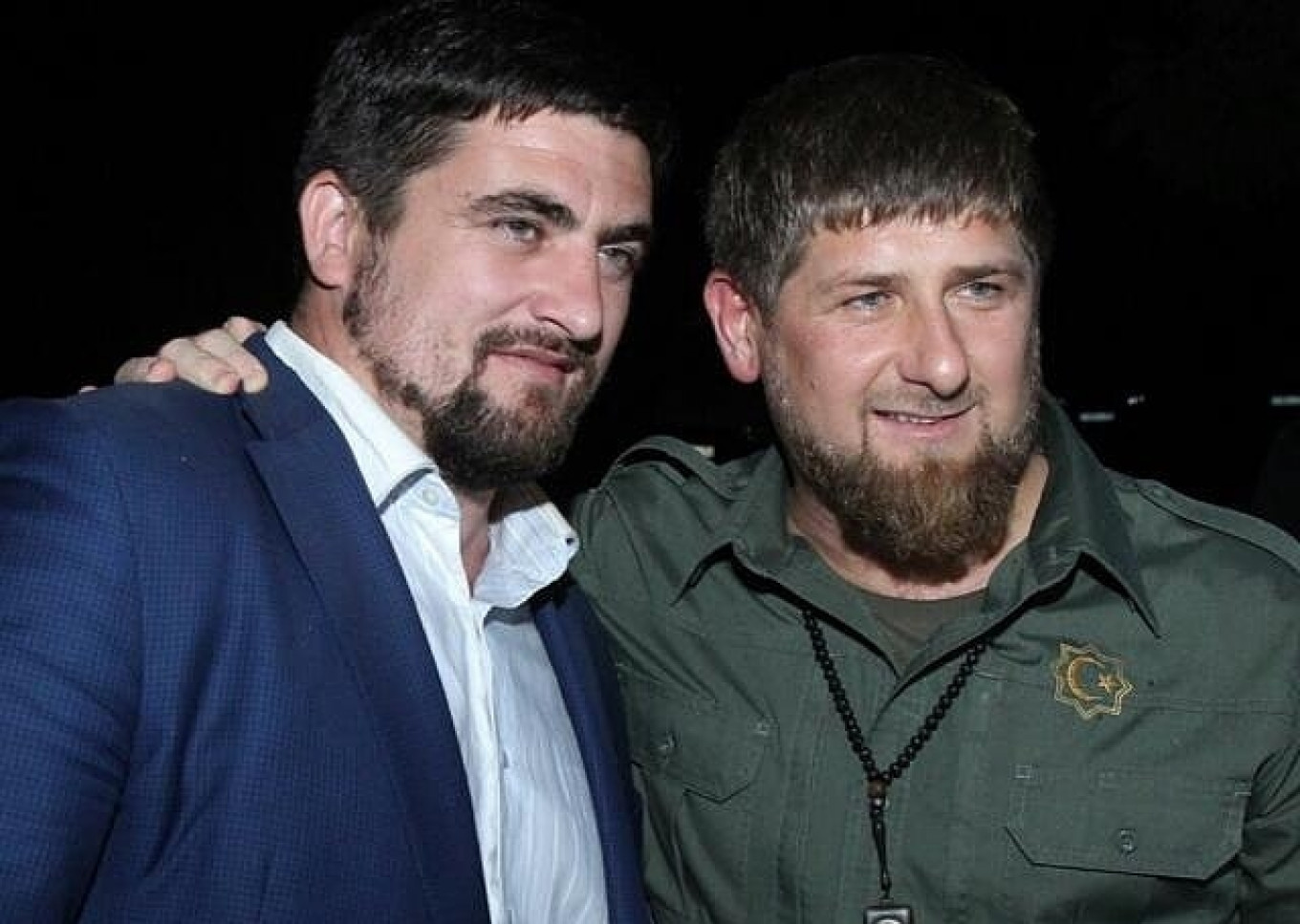

ChechenFilm is one of only a handful of functioning regional movie studios in Russia, and everything in the nascent Chechen film industry appears to involve Terekbayev. The 36-year old was put in charge of ChechenFilm in 2013 and, with Kadyrov’s personal assistance, transformed it into a private film studio. Beyond managing the studio, Terekbayev serves as a director, producer, script writer and, occasionally, actor. He also leads Chechnya’s State Cinematographic Department, which channels financing and administrative support to ChechenFilm, and Terekbayev is slated to become the head of a re-vitalized North Caucasus Film Studio this year.

During a recent interview in his central Grozny office — alongside vast portraits of Kadyrov and his father — Terekbayev told The Moscow Times that it was his childhood dream to work in film. Instead, he became a pediatrician — but he quit his full-time job as a doctor and hospital director in 2012. He named Mel Gibson’s Braveheart as one of his favorite films, and recalled watching the movie on VHS during the First Chechen War, a bloody fight for independence from Russia that tore apart the region in the 1990s. “The film left a very deep impression on me,” he said.

The Kadyrov Brand

Childhood dreams aside, Terekbayev’s ties to Kadyrov have clearly played a role in his rise. According to the filmmaker, his father was a close friend of Kadyrov’s father. After a Dec. 23 visit to ChechenFilm’s new offices in Grozny, Kadyrov praised the company on his Instagram account. Terekbayev said that Kadyrov has ensured they can film in any facility — from airport to stadium — in the region for free. “He takes part in these projects to stimulate young people to do good,” Terekbayev said.

The Chechen leader’s interest is not purely altruistic. As leader of the republic, Kadyrov has embraced social media, photographs and film to boost Chechnya’s profile within Russia and enhance his own grip on power. In 2011, Hollywood stars Hillary Swank and Jean-Claude Van Damme attended Kadyrov’s 35th birthday celebration in Grozny. There, they publicly praised the Chechen leader. After criticism by human rights groups, Swank later fired her manager and said she regretted her decision to attend. Two years later, Kadyrov welcomed glamorous British actress Elizabeth Hurley and French actor Gerard Depardieu to Grozny to shoot part of a film called “Viktor.”

Some of the ambitions of ChechenFilm appear to mirror those of Kadyrov, who has transformed himself from a former warlord into a national politician. While Kadyrov’s comments often cause outrage among liberals in Moscow, he has successfully portrayed himself as a devoutly religious, physically strong leader, able to project his power all over Russia.

ChechenFilm would like to expand well beyond the North Caucasus. “Our plan is to seize the world through cinema,” said Terekbayev. “We are building our turnover and growing our muscles. In five years the whole world will know ChechenFilm. It will be releasing more films than any other Russian film studio.”

No Opposition

Critics say Kadyrov’s authoritarianism means that, regardless of how the Chechen film industry grows, there is no way to make art in the republic. The authorities are afraid of the truth, says Inal Sheripov, who founded ChechenFilm in 2009. “If you articulate an independent position not agreed in advance with the authorities they perceive it as dangerous for them, a threat,” he said. “Why? Because others could follow that example.” Sheripov said he was forced to abandon his work at ChechenFilm in 2012 after he refused to shoot a film about Kadyrov’s father. Shortly thereafter, Sheripov moved abroad and has never returned to Chechnya.

His fear is not unfounded. Kadyrov has been linked to the killing of human rights activists and critics living abroad in Dubai and Vienna, as well as to the murder of Russian opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, who was gunned down outside the Kremlin in 2015. In these conditions, a movie company in Chechnya could become commercially successful, but would never be able to make critically acclaimed cinema, Sheripov said. He dismissed the works of ChechenFilm as “student level.”

Karen Shakhnazarov, the head of leading Russian movie studio Mosfilm and a prominent director, said that he had never heard of ChechenFilm. “Sometimes films appear from the regions, but, as a rule, it is private money and only one or two films,” he said.

Call of the Heart

Terekbayev disagrees with these assessments. ChechenFilm has no need to for Western freedoms and should not seek to imitate the more successful Hollywood model, he said. Instead, it should focus on moral content acceptable under Muslim values. He predicts that his films will find a receptive audience in Islamic countries. “We can’t make films that young people watch and turn bad,” he said. “We will shoot a different sort of film.”

None of ChechenFilm’s productions show men and women touching, in line with public customs in many conservative Muslim societies. “Call of the Heart,” the ChechenFilm television series, shows a young man from Grozny who is estranged from a girl he is courting because of his social position. The plot line emphasizes the moral values promoted in Kadyrov’s Chechnya — from religious devotion to the upstanding nature of law enforcement officers. Sex scenes, swearing and the depiction of alcohol and cigarettes in movies are tell-tale signs of a failed director, Terekbayev said. “I don’t want freedom. We can’t allow ourselves this. No-one in the world has freedom,” he said. “If people show nonsense, that’s not freedom. We are guided by responsibility.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.