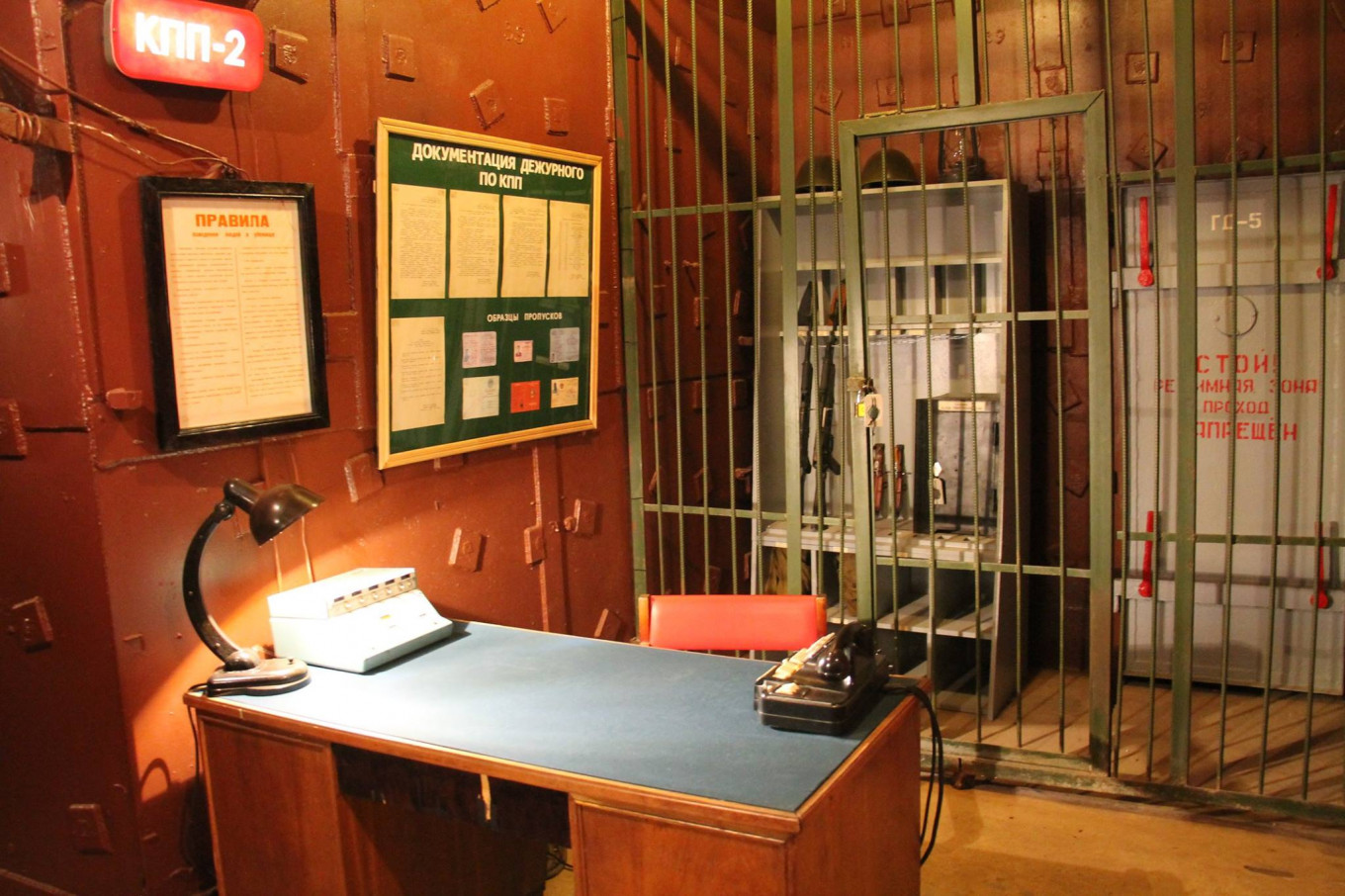

In a fortified nuclear bunker, sixty-five meters below Moscow, a man sits transfixed by a computer console. Its green text informs him of an impending threat. “On my command, turn the key and prime the weapon,” the man behind him barks with the melodrama of a Bond villain. He reaches across the mass of buttons and levers in front of him and turns the key. A countdown begins.

“When the timer reaches zero, turn the second key and hit the launch button!” he commands.

Three. People watch. Two. His finger hovers over the red button. One. His right hand grabs the key. Zero. A nuclear strike against the United States, sworn enemy of Lenin’s Revolution, is launched.

A Requiem for a Dream soundtrack, which echoes through the steel shell of the bunker,

brings spectators back down to reality. It

is just a game — played out in Bunker 42,

a fascinating museum and a relic of the

Cold War.

Bunker 42 is just one of a number of

venues across the capital embracing a

newfound interest in Soviet nostalgia.

More than 25 years on from the collapse of

the USSR, Russia is reestablishing its influence

on the world stage, and memories of

the Cold War hold new weight.

115172, 5th Kotelnicheski Lane. 11

Generation Pepsi

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, social

welfare gave way to uncertainty and

predatory capitalism. Millions lost their

jobs. Hyperinflation wiped out Russians’ life savings. As

cult author Victor Pelevin put it in his novel Homo Zapanians,

Russia exchanged “an evil empire for an evil banana

republic.”

“My family and I suffered great trauma,” Olga, a 52-year-old market-stall owner near Muzeon Park, told The Moscow Times. “Our country was the most beautiful in the world, we were proud of it. Then suddenly, it was gone.”

The narratives of the older generations share a common

thread — the feeling of drifting into the unknown. And

Moscow’s Park Muzeon, or Park of the Fallen Heroes, is the

material manifestation of this drift.

Here you can find statues that were torn down during

the collapse of the USSR. Busts of Lenin are thrown around

chaotically throughout the park. A noseless Stalin watches

on. Even more controversial is the monument of Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Soviet secret police. This was the

first statue to fall with the regime.

Their bold outlines, created in traditional socialist-realist

style, remind passersby of the one-time ubiquity of the Soviet state.

119049, 2 Krymskiy val. 2

Culinary Revolution

Somewhat at odds with the values of communism, Soviet

nostalgia has also crystallised into an easily marketable

consumer brand.

The trend is visible across Moscow: from restaurants

such as Kommunalka, which borrows its interiors from

those of the USSR’s communal apartments, to the ironic

Soviet-style abbreviations used by bars such as Glavpivmag

(built from the Russian words Glavniy-pivnoy-magazin, or

main-beer-store).

The most visible display of Soviet nostalgia is arguably

GUM’s supermarket, Gastronome No.1. The store is packed with immediately recognizable

goods like the USSR’s

famed Plombir vanilla icecream,

marketed as “the

taste of childhood.” There

are strange, cone-shaped

glass containers filled with

drinkable syrup and even

chocolate flavoured butter,

a throwback to the days before

Nutella flooded Russian

kitchens.

For many, products of

the Soviet era embody a

sentiment of forgotten

quality. At a time of sanctions

and counter-sanctions,

they also cross over

into defensive feelings of

national pride.

“Food is getting better

now, and there are standards

again,” one shopper

told The Moscow Times

despite that the quality of

food in Russia has actually

diminished rapidly since a

trade embargo began in 2014.

Many of the new outlets sentimentalize the Soviet era

as a time of innocence and simplicity. These ideas, for example,

are at the heart of the Varenichnaya No.1 chain of

cafes. Old books line the shelves and wall-mounted black

and white televisions play Cold War-era movies. You can

even try traditional vareniki (dumplings) with a side order

of pickled vegetables from jars.

Occasionally, things have gone too far. In December

2016, a Moscow restaurant called NKVD — after Stalin’s

brutal secret police — opened to widespread criticism.

Many condemned the business for profiteering from the

victims of Stalin’s regime. The building of the restaurant

itself was the one-time home of 4 people later executed

during the Great Terror.

101000, Red Square. 3

Simulating

Socialism

Soviet nostalgia is not limited

to older generations.

Russia’s youth has also taken

to this bygone era. At the

Museum of Soviet Arcade

Games, for example, hip

Russian teens spend their

evenings putting Brezhnevera

coins or “commie quarters”

into game machines

produced by the Soviet government

in the late 1970s.

The Museum also offers

a trendy burger bar, 8-bit

gaming soundtracks, and a

gray, hard-edged soda machine

from the early 1980s.

One of the most popular

games in the arcade is Repka

(Radish). This is a test of

strength that requires the

player to pull on a lever as

hard as they can in order to pull a radish out of the family

garden. The game registers the number of kilos they

can pull and ranks the player accordingly. The classics are

all here too: the Soviet submarine shooter “Sea Battle,” the

World War II flight simulator “Dogfight,” and the racing

game “Magistral.” If you visit the museum’s website you

can even play their online simulations of the games and

see inside the machines to get an idea of how they work.

Unfortunately, none of the games keep high scores —

Soviet society, after all, didn’t believe in competition. But

this doesn’t seem to deter the regulars.

“It’s a cool place to hang out with your friends,” one tells

The Moscow Times. “People usually play on their laptops at

home, but this is real old school — what previous generations

did before they invented the Internet.”

Kuznetsky Most. 12

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.