The headline-grabbing decision by the International Criminal Court (ICC) last month to issue an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin on war crimes charges has caused nervousness among the Russian elite, according to current and former officials who spoke to The Moscow Times.

While Russia formally condemned the decision, with ex-President Dmitry Medvedev even threatening to fire missiles at the ICC headquarters, behind the scenes there has been concern about the possible political ramifications.

"This is essentially a call to overthrow the government in Russia,” a parliamentary deputy from the ruling United Russia party told The Moscow Times.

In particular, the Russian elite is worried about threats to political stability resulting from the ICC’s decision, how it makes Putin appear on the world stage and what it means for the Russian president’s ability to travel abroad, according to seven Russian officials who spoke to The Moscow Times on condition of anonymity.

A special meeting was even convened in the Kremlin to discuss Russia’s domestic and international response a few days after the ICC announcement, a Kremlin staffer and a senior official in the ruling United Russia party told The Moscow Times.

The meeting was attended by officers from the department of the Federal Security Service (FSB) that is charged with protecting the regime from internal threats.

The ICC arrest warrant, issued on March 17, targeted both Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s children’s commissioner, who are now wanted for war crimes related to the illegal transportation of children from Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine.

One Kremlin official told The Moscow Times that he was alarmed when he heard the news.

“My first thoughts were of that poor man [ex-Serbian leader Slobodan] Milosevic,” he said.

At least officially, the Russian response has been combative, with officials denying the legitimacy of the ICC while also aggressively attacking the court, its judges and countries that might seek to enforce the arrest warrant.

The decisions of the ICC are "legally negligible," Dmitry Peskov, Putin's spokesperson, said on the day of the announcement.

Hours later, the head of Russia’s Investigative Committee, Alexander Bastrykin, ordered his staff to establish the identities of the judges who made the decision. Three days later, the Investigative Committee announced that a criminal case had been opened against three ICC judges and ICC Prosecutor Karim Ahmad Khan.

Ex-President Dmitry Medvedev even went so far as to threaten that Russia would attack the ICC court in The Hague with hypersonic weapons.

At the same time, however, some in the Russian elite appeared genuinely baffled by the ICC’s decision.

A senior Russian government official who wished to remain anonymous told The Moscow Times that the arrest warrant was "stupid.”

"When the war is over, how will they talk to Putin? The complete lack of logic in the West's actions is somewhat discouraging,” he said. “Or I don't understand it.”

For a domestic Russian audience, the Kremlin’s reaction was more nuanced — but also focused on making the ICC’s decision seem illegal or inconsequential.

The Kremlin asked officials across government for ideas for possible responses to the ICC warrant, according to a Kremlin official and senior figure in the Russian parliament.

“Some of the measures were aimed at delegitimizing ICC decisions inside the country,” said a source close to the Kremlin.

“Who knows what else the ICC will come up with in the future?”

Children’s commissioner Lvova-Belova, the other Russian official sought by the ICC, held a press conference on April 4 in which she defended her actions when it came to removing children from Ukraine and downplayed the significance of the arrest warrant.

“The charges are very abstract. We haven’t received any documents. We don’t understand what we are accused of,” she said. “It all looks like a farce.”

But Russia’s main domestic response appears to be amendments submitted earlier this month to the State Duma that would effectively outlaw the ICC.

If passed, the changes would grant the president power to “protect citizens in the case of decisions by foreign international bodies that contradict Russian legislation” and impose harsher penalties for aiding international organizations.

“This decision will allow us to protect the country from various international organizations’ illegal, unfriendly and aggressive actions,” said State Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin.

Perhaps the most obvious sign of alarm over the possible repercussions of the ICC warrant was the initial reaction to the news by Russia’s state-run television channels.

The first news broadcasts after the ICC decision simply ignored mentioning the arrest warrant or addressed it only in passing.

By the next morning, Russian television had “forgotten about this news altogether,” according to an assessment by independent media outlet Agentsvo.

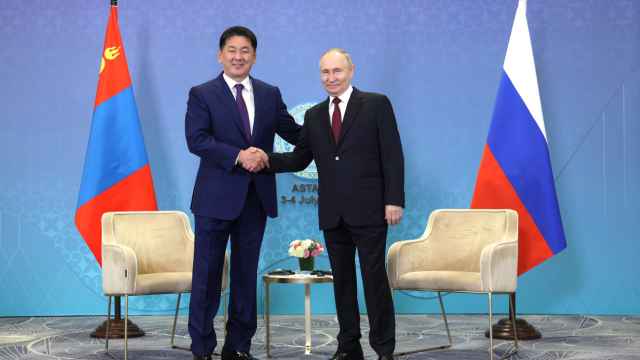

Ultimately, the most immediate consequence of the court warrant has been to throw some of Putin’s travel plans in doubt, with ICC member countries — legally obliged to hand over the Russian leader if he steps onto their soil — confronted with a diplomatic quandary.

While Putin has yet to cancel any foreign trips, it seems likely that he will need to in the future.

A spokesperson for South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said earlier this month that the ICC’s warrant had put a “spanner in the works” for the planning of an August BRICS summit that Putin is due to attend.

The next G20 summit, one of the last major international groups of which Russia is still a member, will be held in India. Although India is not a signatory to the ICC, the Kremlin has yet to confirm that Putin will travel to the event.

Six former-Soviet states, including Central Asia’s Tajikistan, are already members of the ICC and the South Caucasus nation of Armenia has pushed ahead to ratify its membership despite the arrest warrant for Putin.

In either case, the Kremlin is determined to minimize the effect of the ICC warrant on Putin’s international reputation.

Speculation about whether the Russian leader will be arrested if he travels abroad is unproductive, according to a source close to the Kremlin.

"These discussions naturally displease the Kremlin,” he said. “It would like them to end.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.