Russia’s Defense Ministry is particularly active when it comes to outreach. Besides the ministry’s official website, the armed forces also issues specialist printed publications. These include the newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), the magazines Voennaya Mysl’ (Military Thought) and Zarubezhnoye Voennoye Obozreniye (Foreign Military Review) and 18 other newspapers and magazine titles which were mostly inherited from the Soviet period.

All of these publications have quite small circulations; Krasnaya Zvezda, released thrice weekly, has the largest print run at 27,600 copies. But this is changing; over the last decade, the Russian military has been attempting to grow its audience. How successful have they been?

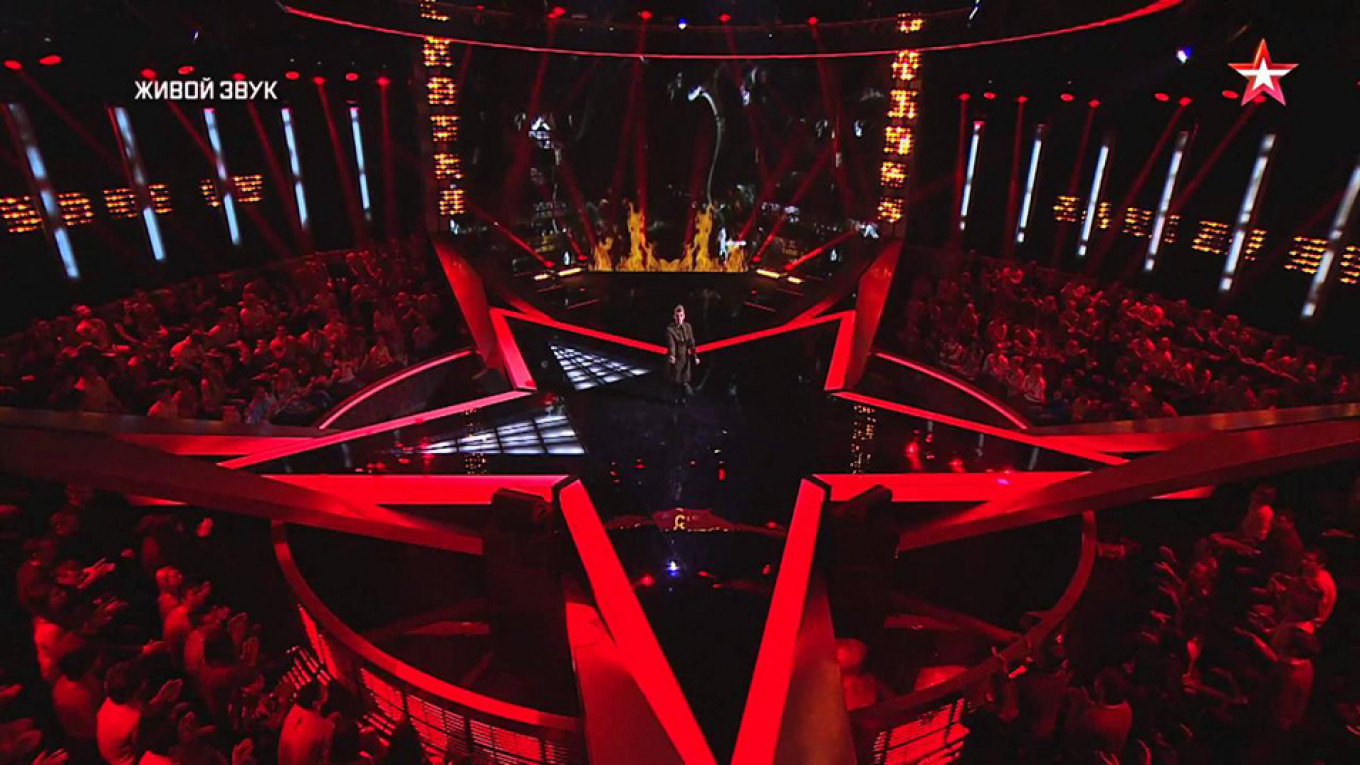

In 2009, during reforms to the Russian armed forces, the Defense Ministry founded the Zvezda broadcasting service. Today the company’s television channel of the same name is one of several TV channels broadcast for free across the entire country. Zvezda also operates an FM radio station called Radio Zvezda and a news website. It is mostly funded by targeted subsidies from Russia’s state budget and contracts with the Defense Ministry.

Furthermore, the Defense Ministry also maintains an official YouTube channel (which has an audience of 137,000 subscribers and 154 million views) and accounts on other social media websites. In comparison, the official YouTube channel of the U.S. Department of Defense has 87,000 subscribers and a little over 17 million views.

Russia's Defense Ministry has 154 million views on YouTube versus the U.S. Department of Defense's 17 million views.

Of course, media outlets belonging to the armed forces are not a Russian innovation. One example is the Defense Media Activity or DMA, of the U.S. Department of Defense. The primary goal of the DMA is to provide information to American military personnel serving in the country or at bases overseas. Meanwhile, information outreach is conducted through official websites and press accounts on social media.

Another example is China, where the People’s Liberation Army releases the daily newspaper Jiefangjun Bao (PLA Daily), whose goal is also to keep military personnel informed. The PLA also maintains a special English-language website, China Military Online, which provides information on the activities of China’s armed forces to an international, mostly professional, audience.

In this context, the activities of the Russian military’s media outlets look quite extensive. This push into the media sphere has clear political objectives.

Firstly, it helps inform both military personnel and society at large about the military’s activities, playing an active role in shaping the public narrative about the armed forces. Secondly, it thereby creates a positive image of the military in that public narrative. In short, it is effectively a propaganda effort with a clear ideological component. However, the results of these frantic efforts actually look very contradictory.

For the starry-eyed nostalgics

Back in the Soviet period, the Defense Ministry experimented with television in some of its publicity efforts. After 1991, these attempts were continued by what had then become the Russian armed forces. However, due to problems within the military, these television programs never proved particularly popular or successful. But that did not deter the military's top brass, which persisted in attempts to gain an on-air presence on television and the radio.

Thus the Zvezda TV channel first appeared in the mid-2000s; it was initially a modest undertaking but in 2009 the channel became the core of a fully-fledged television and radio broadcasting network. The ministry’s leadership at the time hoped to play an active role in covering the huge transformations taking place in the country at the time; transformations which had provoked resistance within the military and heated tensions in Russian society.

The military’s media, like all other media, faced the problem of identifying its target audience and what content to offer them. Interestingly, from its very inception, the management of Zvezda relied on common stereotypes in determining its audience, which it generally considered to be family men aged 35 years or over (men who were “patriots of their country, formed during the Soviet period.”) It is clear that the interests and preconceptions of advertisers, who have clearer and simpler understandings of their audience, played a role here.

Nevertheless, during the past decade, this generation, even those who were teenagers when the Soviet Union collapsed, entered their 40s. Yet through inertia, this demographic remained at the heart of Zvezda’s planning; the broadcasting network continues to operate with an artificially constructed image of a mature “patriot” as its archetypical audience.

By defining its audience in this manner, Zvezda ignores the significant number of women in the Russian military: almost 45,000 women serve in the army, and another 315,000 work in civilian positions at the Defense Ministry.

Almost 45,000 women serve in Russia's army, and another 315,000 work in civilian positions at the Defense Ministry.

According to data from the Mediascope marketing firm, from 3-9 June 2019, the Zvezda TV channel was watched by 2.5% of viewers over four years old across Russian cities with a population of over 100,000. This puts the channel in 13th place out of 32 channels in terms of average daily audience.

In comparison, Russia’s main state television channels Rossia-1 and Channel 1 were watched by 12.1% and 9.7% of viewers respectively, putting them in second and third place in the rating (the total audience of the channel which came in first place was 14.6%).

Among children and adolescents (i.e. groups which the Russian authorities intend will serve in the army in the future), the Zvezda television channel came in 24th place (at just 0.6%). For viewers aged 18-54, Zvezda came in 14th place (2%). The channel proved the most popular among viewers aged 55 and older; but even in this case it only came in ninth place (3.3%).

Remarkably, Zvezda does not even enter the 100 most popular television channels for any age group above four years old. It is important to add here that the general picture presented by the data remains stable from week to week.

Interestingly, the most popular content broadcast over Zvezda TV has long been and remains films about World War II, alongside detective shows and other television series from the Soviet era. This not only illustrates the importance of Soviet nostalgia to the channel’s appeal, but also that its audience is attracted to Zvezda primarily for entertainment content from those “glorious times.”

From this we can conclude that the typical Zvezda viewer is someone who feels uncomfortable with the realities of modern Russia; someone who is afraid of projecting their hopes onto the future and, due to this passivity, takes refuge in the past. When faced with such an audience, the tasks of PR, political propaganda and simply providing information become nearly impossible.

What of Radio Zvezda, which broadcasts on FM radio, a very popular medium, in several dozen large Russian cities? According to data from TNS, its average daily audience from October 2018 to March 2019 was about 1.25 million. Nevertheless, this is still dwarfed by the average daily audience of Russia’s 30 largest FM radio stations, which amounts to almost 40 million.

Russians tune in to music radio stations more than any others, but this fact has not helped Zvezda: although Radio Zvezda has a popular music broadcast, its audience is almost 2.5 times smaller than that of Echo Moskvy — a purely “informative” radio station known for its on-air discussions — which has 3.13 million listeners.

Zvezda’s news website presents a similar picture. According to Yandex, since the start of 2019, visits to the website have fluctuated at around 360,000–380,000 visitors per day, even accounting for return visits by the same user, or visits by the same user from different devices. The monthly number of unique visitors to the website stands at six to seven million — last place in the list of the 30 most popular online Russian media outlets.

In comparison, the state-owned RIA Novosti news agency attracts a monthly audience of 27.5 million and a daily audience of 3.2 million. When put in a global context, the figures for Zvezda’s website appear quite respectable; China Military Online has a daily audience of 60,000–80,000 users. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that this Chinese website is aimed at specialists based outside China, while Zvezda aspires to reach a much broader audience.

If we regard the Zvezda company solely as a commercial media holding, then it clearly occupies its own niche in the Russian media market. But it would not be entirely accurate to do so; the company’s commercial accounts for 2014 (no more recent documents are freely accessible) indicate that it received a subsidy from the federal budget of 1.5 billion rubles (approximately $40 million), as well as special contracts from the Ministry of Defense worth over 200 million rubles ($5 million).

At the same time, Zvezda’s financial performance has deteriorated noticeably. In 2014, net profit came to 282 million rubles (more than $7 million). But in 2017, Zvezda suffered a net loss of almost 58.4 million rubles (nearly $1 million).

Thee generous subsidies to Zvezda amounted to around 2.1 billion rubles in 2019-2020. But despite all this assistance from the state, Zvezda has proved unable to become either a successful media outlet or an important instrument of propaganda within Russia.

An eclectic mix of genres

The Russian military also publishes 10 magazines and 11 newspapers, the best known of which are the aforementioned newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda, military magazines Voyennaya Mysl’, Voyenno-Istorichesky Zhurnal (Military History Magazine), and the analytical magazine Zarubezhnoye Voennoye Obzreniye.With circulations from a few hundred to several thousand and marginal popularity online, these publications are mostly read by officers of the armed forces and to a lesser extent civilian experts.

Therefore the function of these publications is to provide information to highly specialized and narrow groups of professionals. They play no role in the field of PR or propaganda in the wider societal context, and have never done so over the previous decades of their existence. Nonetheless, they do play a role in communicating the political line of the Russian leadership to military personnel.

However, this multitude of specialist periodicals and magazines of different formats and different qualities does not indicate any coherent, unified information policy of Russia’s Ministry of Defense. Instead, they suggest that the military has taken an eclectic, if not incoherent, approach which is therefore very hard to critique objectively.

It turns out that the Defense Ministry's media outlets operate on bureaucratic inertia, lacking any clearly formulated vision. They even appear to have very little influence on Russian society’s largely positive attitude to the armed forces.

With the founding of the Chief Political-Military Directorate of the Russian Armed Forces in 2018, there were grounds to suppose that the new agency would launch wide and coordinated propaganda efforts. But it turned out that the directorate’s real purpose was to increase the morale not of Russian society, but of the Russian military, and to strengthen their loyalty to the Kremlin (a loyalty which, by all accounts, the Russian authorities have started to doubt).

In conclusion, the military’s media outlets will continue to remain peripheral. Ordinary mass media outlets, including state-owned ones, have proven much more effective in informing the public about military matters such as the activities of the army or weapons procurement.

Here we can add organizations closely associated with the state’s military industrial complex, such as the Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. Maybe a special military program for PR and patriotic propaganda is entirely unnecessary, given that the entire machinery of the Russian state is geared towards their production. And that will last as long as military success, or at least the appearance of military success, remains an important tool for securing political legitimacy.

This article was originally published by Riddle.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.