The tired, gray-haired epidemiologist in charge of inpatients at the Moscow Center for Fighting and Prevention of AIDS, says that Russia’s HIV epidemic is exaggerated. “Journalists have very loud mouths,” he mutters under his breath, before signing the papers to authorize a HIV test.

And yet here, inside the unfriendly, shabby corridors of the three-story building in eastern Moscow, there is standing room only. The benches and chairs are all fully occupied. Men, women, expectant mothers, pensioners, married couples spend hours in lines — arguing about whose turn comes next, who goes in after who.

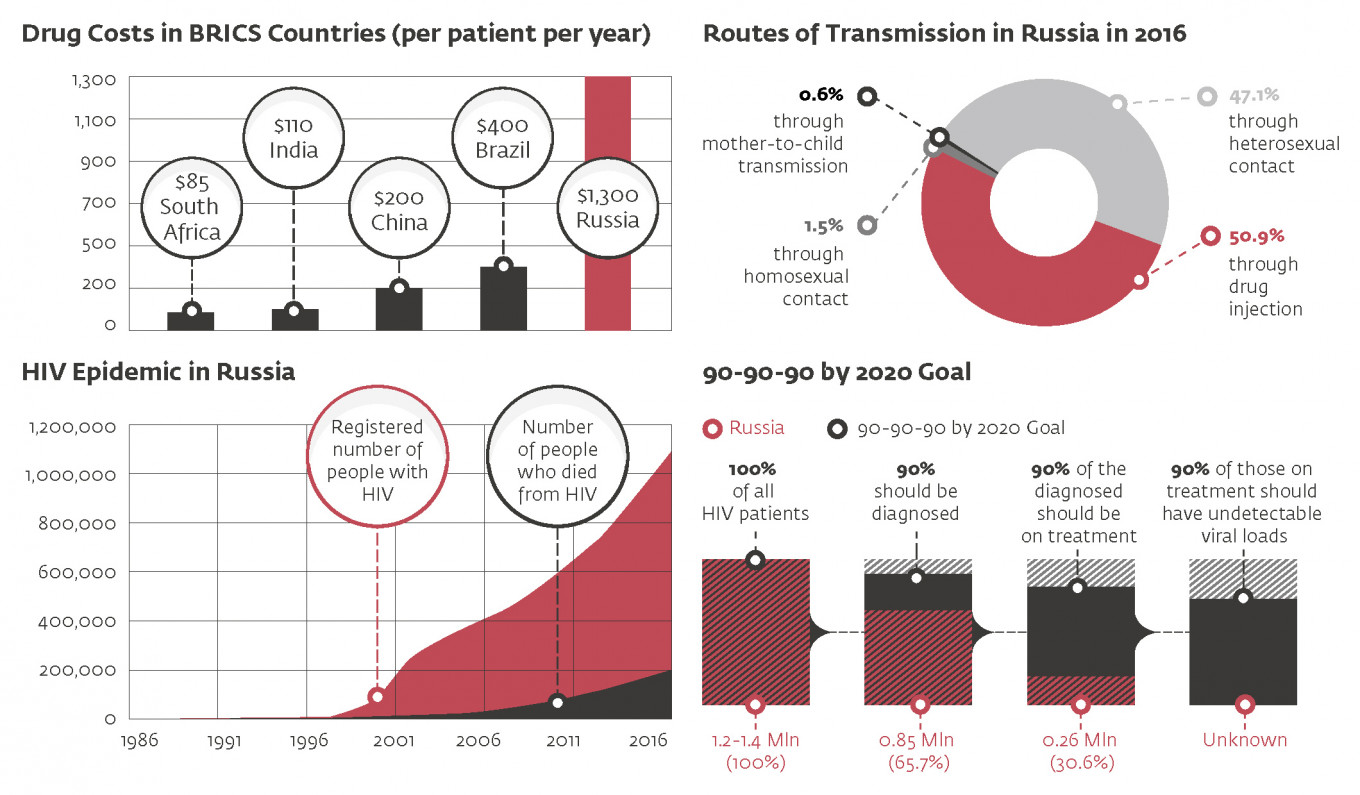

As of Sept. 30, there were 854,187 Russians registered as living with HIV. The number has been growing steadily since late 1990s, and has been increasing while the number of new cases has been falling in developed countries. In 2015, 95,475 new HIV cases were registered. During the first nine months of 2016, another 75,962 HIV diagnoses were handed out. UNAIDS has reported that Russia has the largest HIV epidemic in the European Region, and one of the fastest growing HIV epidemics in the world.

“The HIV epidemic in Russia is not an abstract, theoretical threat. As noted at the highest levels of the Russian government, HIV in Russia has reached a critical level, and the epidemic is getting worse by the day,” Vinay Saldanha, UNAIDS regional director for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, told The Moscow Times.

Indeed, for the first time in decades, Russian officials seem to be alarmed. Just last week, Health Minister Veronika Skvortsova described the situation as “critical.” And two weeks earlier, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed off on a new government strategy designed to get the epidemic under control by 2020.

The Medvedev strategy is, however, conspicuously vague. For the most part, it describes the importance of preventing the spread of the infection and treating those already infected. How exactly the government intended to do this with policy changes and action is less clear.

The world already knows quite a bit about HIV, and there are few excuses for not dealing with it. “Other than being able to completely cure someone — and scientists are already getting close to cure someone with HIV — we certainly know how to stop it,” says Saldanha.

Russia’s ‘Patient Zero’

Russian authorities started monitoring HIV in 1985. For more than a decade, the situation was under control. But in 1997-1998, HIV numbers increased dramatically, as the virus spread to intravenous drug users.

Drug users were Russia’s collective “patient zero,” says Vadim Pokrovsky, head of the Moscow-based Federal Center for Fighting AIDS, and Russia’s most eminent HIV specialist. “In the 1990s, the ruble became a convertible currency, which meant that huge amounts of money could be earned selling drugs,” he says. Hungry for cash, drug dealers increased the circle of addiction among young Russians. At some point, HIV started spreading among them.

Today, more than 50 percent of new cases are from drug use. “This is where it starts,” says Pokrovsky. “Drug users have sexual contacts and infect other people, who, in turn, infect their partners.”

The epidemic might have been nipped in the bud, had Russian authorities implemented timely drug substitution programs. This treatment is generally considered one of the cornerstones of HIV prevention. Not only does it prevent people from getting the virus via dirty needles in the first place, but it also helps infected drug users stick to HIV treatment regimens.

“It is difficult to make sure drug users take the medicine,” says Pokrovsky. “But if you have substitution programs, you can offer HIV medicine together with the substance that substitutes drugs.”

Implementation of the substitution therapy was under discussion in the 1990s, but it never achieved widespread support. Reactionaries within government staged a rearguard action against the programs, and some HIV specialists argued against it.

And the number of HIV patients continued to grow.

The One Percent

In December 2015, the number of cumulative registered cases of HIV in Russia reached over 1 million (this includes more than 200,000 who have already died from the virus.) Together with undiagnosed cases, the prevalence of HIV in the Russian population is today estimated at 1.2-1.4 million, according to Pokrovsky.

“One percent of the entire Russian population, age 15-49, is diagnosed with HIV,” says Saldanha. “This is very alarming.”

Even as Russia passed the 1 million milestone, it showed little fight in trying to turn the tide. The funds available for dealing with HIV are currently only sufficient to cover treatment for 261,557 patients, less than one third of those officially diagnosed. The country’s HIV infrastructure is worn out and outdated. Little more than 100 AIDS centers operate across the country. They provide treatment and medical care to HIV patients, but resources are stretched and there is no spare capacity.

Treatment itself is of low quality and often irregular,

says Andrei Skvortsov, a coordinator at the “Patients In Control”

project, which monitors medication supplies all over the country. In the

past six years, the project has received dozens of complaints about

medication shortages in different

Russian regions. Skvortsov expects the shortages will only continue,

given the fact that the budget for HIV treatment is subject to constant

cuts.

Read more coverage about HIV drug shortages in Russia: Russia's HIV Patients Struggle to Get Treatment

“The worst thing is that health officials are now opting to buy cheaper drugs, and some of them have awful side effects,” Skvortsov says. “Their logic is: ‘you’re going to take whatever we give you.’”

What is more, the treatment is also only usually guaranteed at an advanced stage of the disease, when the patient’s immune status reaches 350 CD4 cells or less (compared to 700-1100 CD4 cells of a healthy immune system). “The latest Russian clinical guidelines still state that anyone with HIV should be treated, but in most regions, clinicians initiate treatment only at 350 [CD4 cells] or under,” says Saldanha. “By contrast, most countries in Europe, Asia and Africa are quickly moving to implement WHO’s latest recommendations for ‘test and treat,’ which is essential to ensure that people with HIV stay healthy and do not transmit HIV to others.”

WHO’s new HIV treatment guidelines recommend that everyone with an HIV diagnosis is offered access to immediate HIV treatment, regardless of CD4 count. By immediately tackling infectiousness, it has contributed significantly to containing the disease in more advanced countries.

90-90-90

Another key yardstick is what is known as the 90-90-90 target. This states that by 2020 a country should look to diagnose 90 percent of all people estimated to be living with HIV, put 90 percent of those diagnosed on treatment, and reduce viral loads to undetectable levels in 90 percent of all those being treated. With undetectable loads, the virus is essentially suppressed — neither harmful to the carrier’s health nor effectively transmittable to others.

Once you reach the 90-90-90 goal, several positive things happen. The rate of AIDS morbidity and mortality drops, and with the additional impact of treatment as prevention, the epidemic becomes manageable. “Suddenly no one with HIV gets sick, hundreds of thousands of people no longer occupy hospital beds and a huge burden is taken off the shoulders of the medical system,” says Saldanha. If the 90-90-90 milestone is reached, 73 percent of all people infected with HIV have undetectable viral loads, and two-thirds of the epidemic can be brought under control.

In June, all UN member states — including Russia — committed to a “90-90-90” target by 2020.

Russia has a long way to go to reach this goal in terms of sheer numbers. The Russian government has yet to come up with effective HIV prevention policies.

“HIV treatment is essential, both for saving lives and having an impact on HIV prevention, but no country has ever successfully treated their way out of an HIV epidemic,” Saldanha says.

It is not clear how the authorities plan to prevent the virus from spreading among injecting drug users. The new Medvedev strategy offers few clues to that effect, says Pokrovsky. “Until we solve the problem with drug users, we can’t solve the others,” he says.

Sabotage

With drug substitution therapy deemed illegal, there is only so much that can be done to prevent transmission among Russian drug users. One of the only remaining effective means of alleviating the problem is via needle exchange, or “harm reduction” programs.

But even here, Russian officials have been engaged in active sabotage. According to Anya Sarang, president of the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, an NGO that works with drug users and HIV patients, it has become increasingly difficult to operate harm reduction programs since a decision by the Health Ministry in 2009 to announce it was against harm reduction programs. “This has resulted in a huge reduction in the number of such programs being delivered in Russia,” Sarang told The Moscow Times.

Even in 2009, there were only 75 harm reduction programs, covering no more than 135,000 of the estimated 2.5 million drug users in Russia. Today, that number is even less — 16 programs for 13,000 drug users. “At this scale, projects can only help individuals, but do nothing to stop the epidemic,” says Sarang.

This year the pressure was ratcheted up further, as five HIV-related NGOs, including the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, were added to the list of “foreign agents” register. This controversial legislation makes organizations subject to additional bureaucracy, excessive inspection regimes and harassment. “Many NGOs in smaller cities and regions are not ready to stand up to the scrutiny, and simply shut their doors,” says Sarang.

Russian government officials claim that needle exchange and sex education programs promote drug use and unsafe sex practices. Experts are adamant that the claims have no evidential basis. “Take Germany, where sex education is mandatory — there is no HIV epidemic there,” says Pokrovsky. “They also have drug substitution therapy and educate sex workers on safe sex. Obviously, these methods are effective.”

“It is essential to implement evidence-based prevention programs for key populations that represent the majority of new HIV infections,” agrees Saldanha.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.