Spies and spycraft seem to have been the dominant theme in Russian foreign relations this year. There were, of course, the stories of intelligence operations: the Skripal assassination plot in Britain, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons hack in the Netherlands, not to mention the continued drip-feed of allegations and revelations from the Mueller inquiry into interference in the U.S. presidential elections in 2016.

But Russian spycraft also threaded its shadowy way through many other stories.

The conflict in Ukraine is still a hot war, but the real struggle is now political, and Russia’s spooks seem to be doing everything from staging sporadic terrorist attacks to spreading their agent networks in the name of undermining Kiev’s will and capacity to challenge Moscow. In Syria, now that government troops and their militia allies are better able to fight, Russia has shorn up its backing of Bashar Assad beyond airpower by contributing intelligence support — from the satellite photography and radio-electronic plots that help shape the battle, to the quiet infiltration of GRU Spetsnaz commandos, calling down airstrikes and targeting rebel supply lines.

How far can Russia’s enthusiastic embrace of covert activities be considered a success, at least when viewed from the Kremlin? There have, of course, been tactical reversals, and in many ways the Salisbury poisoning can be seen as an example of the whole campaign.

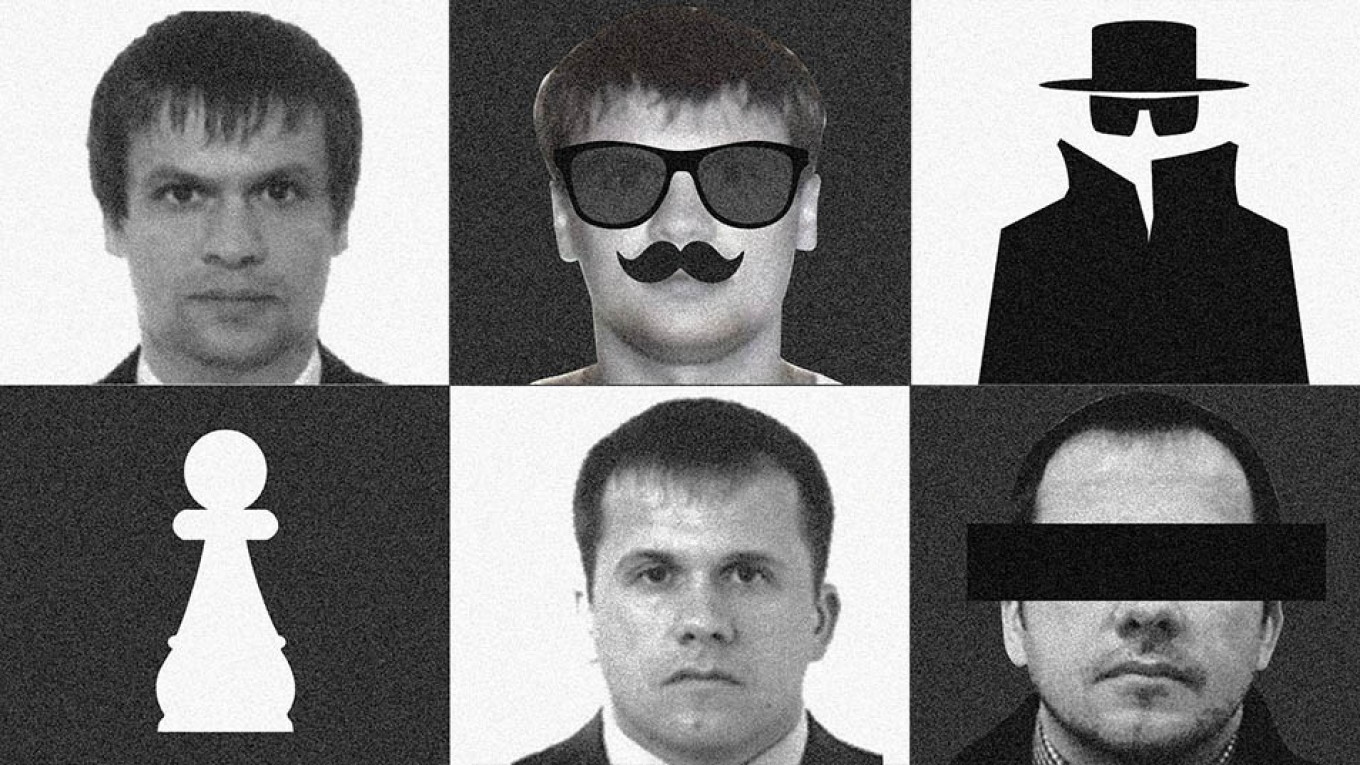

Sergei Skripal — the “scumbag” and “traitor,”’according to Putin — still lives. But the likely wider objective of demonstrating the will and capacity to act in such a flagrant way was accomplished. Even so, in the aftermath of the attack, the two alleged military intelligence officers were unmasked (which was likely predicted) but it also triggered a wave of international diplomatic expulsions (which surely came as a surprise).

So, a partial operational success, a full political one, but also an unexpected geopolitical setback. A score of 1.8 out of 3? Actually, the arithmetic was probably even more favorable. The expulsions were embarrassing, and undoubtedly caused short-term problems as new case officers hurriedly connected with their predecessors’ agents. However, there has been no sense yet of a major and lasting impact on Russian intelligence activity, not least as it is not entirely dependent on officers based under diplomatic cover.

More to the point, there is no real evidence that the Kremlin regards public disclosure as a serious problem. Just as with so many other aspects of Moscow’s geopolitics, there is a theatrical aspect. As the country tries to assert an international status out of proportion with the size of its economy, its soft power and arguably even its effective military strength, it relies on the fact that politics are about perception.

By nurturing a narrative that its spies are everywhere, hacking here, killing there and rigging elections in between, they contribute to Russia’s claim of being a great power, even if an awkward and confrontational one.

After all, the calculation appears to be that there is little scope in 2019 for any major improvement in relations so long as the West remains united. If populist leaders of some countries break rank over European sanctions— however unlikely that appears — then that is a plus. But overall the Kremlin seems to have concluded, not without reason, that it is stuck in confrontation for the long haul. The later U.S. sanctions, based as they are on past misdeeds, offer no clear “off ramps” and especially contribute to the sense that relations are permafrosted.

Short of what Moscow would rightly consider capitulation — a withdrawal from Crimea, abandonment of its adventures in both Ukraine and Syria, and a general acceptance of a global order it feels is essentially a Western-dictate done — then the confrontation is here to stay. So there is no incentive for Moscow to scale down its aggressive intelligence campaign in the West anytime soon.

Instead, lessons are likely to be learned. It is striking that the 2018 U.S. midterm elections showed no serious Russian interference, and likewise their efforts in Europe have been largely to provide some slight support to useful populist groups already on the rise. The risk of more obvious and heavy-handed meddling is not just that it may trigger a backlash — as it has with the U.S. Congress — but also that, quite simply, it seems not to work.

The intelligence-gathering campaign will continue unabated, especially as Putin appears to depend more on his spooks than his diplomats for his picture of the world. Meanwhile, the online realm is very much a key battlefield of the new espionage war, although it is important not to lose sight also of the others, especially old-fashioned human intelligence.

If espionage will remain a ubiquitous threat, then with subversion and active measures the focus will be on softer targets: countries with limited counter-intelligence capacities, with fractured and fractious politics to be exploited and encouraged, with national leaderships unwilling to challenge Moscow directly. The Balkans and southeastern Europe will likely see continued efforts, as may the United Kingdom if Brexit metastasizes.

Fixating on the spies, though, misses the point. There was talk of a purge in military intelligence— still generally known as the GRU even though officially it is just the GU now — after recent revelations. Yet what happened? Putin turned up to its hundred-year anniversary gala, delivered a gushing eulogy and raised returning that errant “R.” The fact is that Russia’s intelligence agencies are doing what the Kremlin wants.

When you feel like an outsider, under threat, being diminished and demeaned by your rivals, you have no incentive to play nice. Instead, you have to turn to whatever options and advantages you feel you have. Clearly the spooks are among Putin’s relatively few such instruments. So while the tactics will evolve, until there is some step change in Russia’s relations with the West, the intelligence campaign will continue.

Mark Galeotti is a senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations Prague and the author of “The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia.” The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Moscow Times. A version of this article appeared in our special "Russia in 2019" print issue. For more in the series, click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.