The confirmation that Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was poisoned with Novichok has heightened calls for Germany to review its support for Nord Stream 2 — Gazprom’s mega gas pipeline project linking the two countries.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel will not rule out consequences for the project if Russia fails to thoroughly investigate the incident, her spokesperson said Monday, raising speculation of a possible reversal of Berlin’s long-standing support for Nord Stream 2, which was supposed to come online by the end of 2019.

Critics — including the U.S. government and many former communist countries across eastern and central Europe — say Nord Stream 2 will be bad for Europe’s energy security and is inappropriate given Moscow’s numerous transgressions against the west in recent years.

Advocates argue that Europe already buys a substantial amount of Russian gas, that the pipeline could help reduce prices and that commercial interests are the root of U.S. opposition.

What is Nord Stream 2?

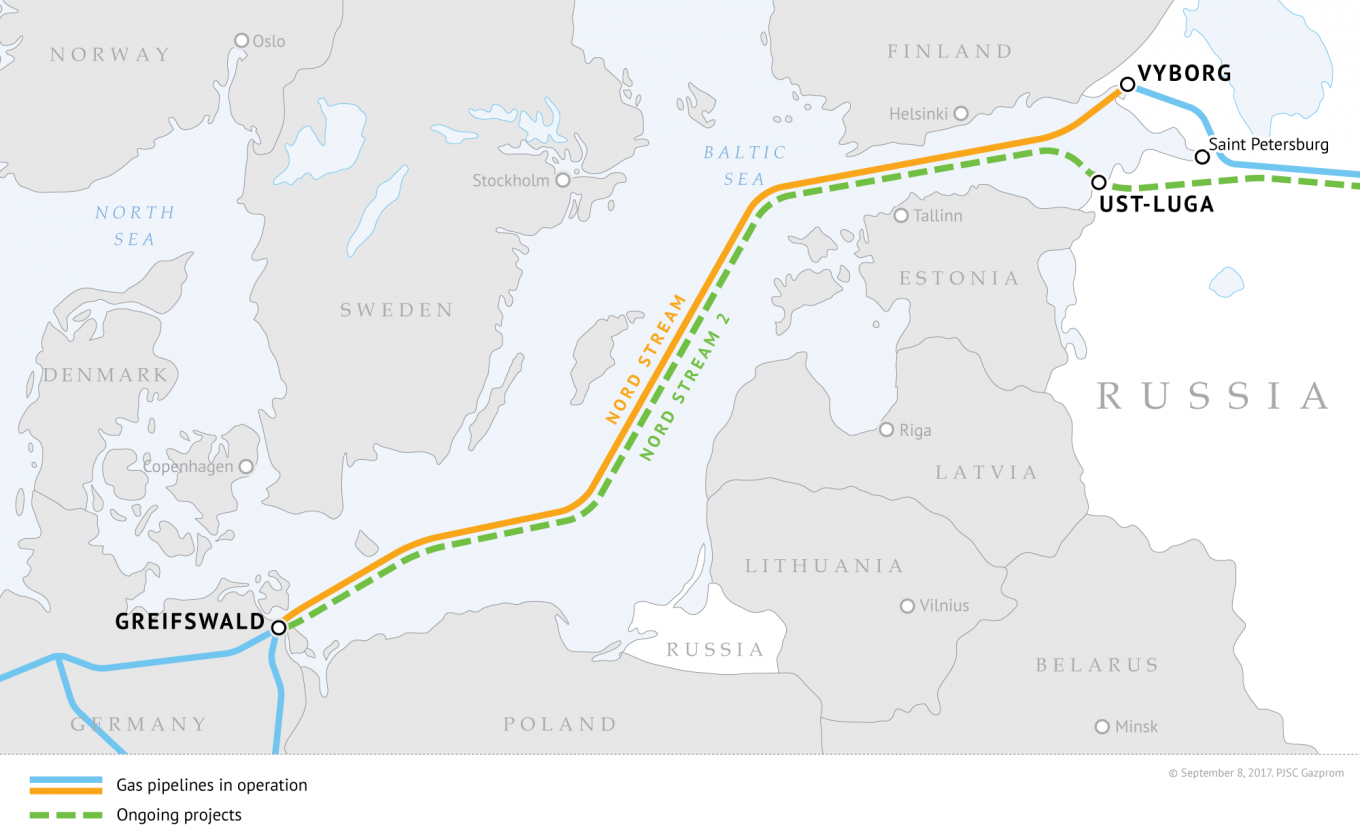

Nord Stream 2 is a twin set of 1,230 kilometer gas pipelines with the capacity to carry 55 billion cubic meters of gas from Russia to Germany every year.

Gazprom has put the total cost of the project at around $10 billion, with half coming from a consortium of European energy companies — Shell, Engie, OMV, Uniper and Wintershall Holding. Gazprom is 51% shareholder in the Swiss-based company Nord Stream AG, which manages the pipeline construction.

The pipeline runs parallel to the existing Nord Stream which came online in 2012. When operational, it will take the combined capacity of the pipelines running directly between Russia and Germany across the Baltic Sea to 110 billion cubic meters — or more than half of Gazprom’s total current gas exports to Europe.

In 2019, Gazprom exported 199 billion cubic meters of gas to Europe according to the company’s website. Around two thirds of the total capacity is through land pipe networks which run through Ukraine or Belarus — countries which take substantial transit fees for the use of their networks.

From Germany, the gas could then be transported around Europe through existing infrastructure. At current price forecasts and operating at full capacity, Nord Stream 2 would pipe around $10 billion worth of Russian gas to Europe every year.

Construction is currently frozen with around 94% of the pipeline complete — the entire route except from a short section through Danish waters.

Why is it controversial?

The project has proved controversial from the start — like the first Nord Stream link when it was proposed more than a decade ago.

Opponents say the project will increase Europe’s reliance on Russia for its energy needs, giving Moscow a strong lever of potential control over the continent.

Countries across central and eastern Europe have opposed the pipeline for years. In 2016, eight EU leaders wrote to the European Commission against the initiative, saying it posed “energy security risks” to the EU.

More recently, the U.S. has become one of Nord Stream 2’s fiercest opponents. President Donald Trump said of the pipeline: “it’s a horrible thing what Germany is doing. Germany is a captive of Russia.”

U.S. ambassadors across Europe have been fiercely lobbying against the initiative both publicly and privately. In an open letter, U.S. envoys to Germany, Denmark and Brussels said recently: “The Nord Stream 2 pipeline will heighten Europe’s susceptibility to Russia’s energy blackmail tactics.”

Another form of criticism is the impact the project will have on Ukraine — where gas transit fees make up 3% of the country’s GDP.

A U.S. State Department fact sheet explaining its opposition to the project states: “Nord Stream 2 is a tool Russia is using to support its continued aggression against Ukraine ... Nord Stream 2 would enable Russia to bypass Ukraine for gas transit to Europe, which would deprive Ukraine of substantial transit revenues and increase its vulnerability to Russian aggression.”

In the most extreme version, some fear Russia could use the threat — or actuality — of turning off the taps to exert political or economic pressure on the EU or governments across Europe.

In a bid to stop the project, the U.S. has levied a number of sanctions against its construction, including banning high-tech western vessels from laying pipes. That has pushed back construction, with a final section through Danish waters yet to be built. Russia insists it will be completed, although it would not come online before next year. Germany said it rejected “the imposition of extraterritorial sanctions” as a matter of principle.

What do its supporters say?

Before the Navalny poisoning, Germany had steadfastly tried to keep the issue of Nord Stream 2 separate from the rest of its Russia policy, including the war in eastern Ukraine, allegations of election interference and cyberattacks, the poisoning of Sergei Skripal in the U.K. and a general deterioration of Moscow’s relations with the west.

Merkel has previously rejected the idea that Nord Stream 2 poses a risk to energy security, and insisted the driving force behind the pipeline was economic — reducing the price Europe pays Russia for gas while it embarks on its decades-long energy transition towards cleaner sources of fuel.

Analysts also suspect commercial interests behind America’s opposition. Namely, a desire to sell more expensive liquified natural gas (LNG) to Europe.

Since Europe already buys around 40% of its gas from Russia, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline is more about the delivery mechanism than overall reliance on Russia, advocates say. Besides, given tensions between Kiev and Moscow, heavy reliance on transit through Ukraine could be a form of instability, with Russia just as able — and perhaps more likely — to disrupt supply through that pipeline, as it did in 2009.

How does the Navalny poisoning affect Nord Stream 2?

Germany’s confirmation that Navalny was poisoned by Novichok — a controlled chemical weapon — has added new fuel to the campaign against Nord Stream 2.

The usual voices of opposition have doubled down on their criticism, insisting Germany rethink the project.

But new voices from inside Germany have also come out against the pipeline.

“This openly attempted murder through the Kremlin’s mafia-like structures should not just worry us but needs to have real consequences. Nord Stream 2 is no longer something we can jointly pursue with Russia” said Katrin Göring-Eckardt, the co-chair of Germany’s Green Party, which is second in the polls to Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU), in the Bundestag as cited by The Guardian.

The chairperson of Germany’s foreign affairs committee and CDU leadership candidate Norbert Röttgen called on Twitter for Nord Stream 2 to be scrapped, writing: “After the poisoning of Navalny we need a strong European answer, which Putin understands. The EU should jointly decide to stop Nord Stream 2.”

In a significant step, the German government itself warned Russia that the future of the project is on the table.

“I hope the Russians won’t force us to change our position regarding Nord Stream 2,” Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas told the Bild newspaper, which also called for the project to be halted in an editorial last week.

A spokesperson for Merkel said that a possible sanctioning of the project was an option. “The chancellor believes it would be wrong to rule anything out from the start,” her spokesperson Steffen Seibert told reporters Monday in response to a question about the Gazprom-controlled project.

What happens next?

Analysts still believe the pipeline is more likely to go ahead than be scrapped, especially given the late stage of its construction.

Any backtrack on Nord Stream 2 would be a monumental shift in policy from Germany, and especially Merkel, who has invested significant political capital in the project against criticism from the U.S. and within the EU.

Just last Friday the Chancellor argued the poisoning of Navanly should be “decoupled” from the issue of Nord Stream 2, adding: “Our opinion is that Nord Stream 2 should be completed.” And despite foreign minister Maas’ warnings, he also said any punishment for the poisoning of Navanly should be “pinpointed effectively” and acknowledged a cancellation would hurt Germany as well as Russia.

The U.S.’ vocal opposition could even backfire, some analysts said, if it makes a reversal on Nord Stream 2 appear to be a climbdown in the face of American pressure.

Nevertheless, the forcefulness of Germany’s response so far — and the personal involvement of Merkel — has taken some by surprise, indicating a potential willingness to act.

“That suggests the depth of her concern about the significance of this. Even a few days ago the intention of the German authorities was again to lay to rest the Nord Stream 2 issue, but this — at the very least — returns it to centre stage,” said Nigel Gould-Davies, senior fellow for Russia and Eurasia at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

In any case, a formal response to the poisoning is at least some weeks away, say experts familiar with the EU’s sanctions process. Germany has said it is “too soon” to begin considering specific punishments, and appears — for now — to be using Nord Stream 2 as a tool to push Moscow to launch a full and transparent investigation into the poisoning.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.