By the time the ban came into effect, Jennifer and Josh Johnston, an American couple, were only one court hearing away from taking four-year-old Anastasia home with them from an orphanage outside Moscow.

“When our time with Anastasia was over, we promised her we would come back and take her. She said she would wait,” says Jennifer.

The happy reunion never happened. In January 2013, Russia introduced the notorious Dima Yakovlev law banning the adoption of Russian orphans by U.S. nationals. “We broke our promise,” Jennifer said, her voice cracking.

Since then, there have been hundreds of sleepless nights and many tears over conference calls with other families hit by the ban with U.S. officials. A mountain of paperwork was also gathered for the class action suit filed at the European Court of Human Rights by 45 U.S. families on behalf of themselves and 27 Russian children.

Four years later, on Jan. 17, 2017, the ECtHR ruled in the families’ favor, stating that the ban unlawfully discriminated against prospective parents on the basis of nationality. The ruling means Russia owes the families financial compensation. More importantly, it has fed hopes that the law could be overturned, and that more than 200 affected families can be reunited with the children they were forced to leave behind.

“We are hopeful that the U.S. and Russian governments can come together and negotiate a way for at least the children who were already assigned American families before the ban to be able to finish their adoptions,” says Katrina Morriss, whose plan to adopt a seven-year-old girl with Down syndrome, Lera, was also crushed in 2013.

However, the Yakovlev law had little to do with either family values, love, or children. In fact, the adoption clause was part of a purely politically-motivated legislative act, to retaliate against the U.S. at a time of geopolitical tension.

Russian orphans were caught up in the geopolitical crossfire in 2013; Four years later, with a new president in the White House, the children affected by the Yakovlev law could become political pawns once more.

A Question of Politics

The Yakovlev law was designed in retaliation for the Magnitsky Act, an American law named after Sergei Magnitsky. A Russian lawyer who had been investigating government tax fraud, Magnitsky died in prison in 2009 of a heart attack under suspect conditions.

In response to the lawyer’s death, the U.S. blacklisted a number of Russian officials involved in “human rights abuses.” A total of 18 individuals were banned from entering the country or owning real estate or other U.S. assets.

In mid-December 2012, Russia introduced a draft bill, tagged the “anti-Magnitsky law,” introducing similar measures against Americans “involved in human rights abuses.”

Several days after passing its first reading, however, an amendment was introduced to the bill to include an entirely new clause imposing a blanket ban on Americans’ adopting Russian orphans.

“It came as a complete surprise,” says Dmitry Gudkov, one of a handful of opposition politicians at the time, and a staunch critic of the Yakovlev law. “Before that, the word adoption hadn’t even been mentioned.”

The alleged danger for Russian orphans across the pond had become a talking point on state media after the much publicized case of Dima Yakovlev, a toddler who died of heatstroke after being left alone in a car by his American adoptive father in 2008.

But the hyped stories of personal tragedy didn’t coincide with Russia’s political agenda until large protests broke out in 2011 and 2012 against rigged parliamentary elections and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency.

“The Kremlin suspected the U.S. of trying to instigate a color revolution, and the adoption ban was an act of retaliation,” says political scientist Valery Solovei.

He argues that the plight of Russian children abroad was also a psychologically effective way of distracting Russians from other domestic issues. “People are always worried about children,” he adds.

By merging the anti-adoption measure with the anti-Magnitsky law, authorities were hoping to avoid a fuss, says political analyst Yekaterina Schulmann.

But the plan backfired — people working in the social services sector and a handful of opposition politicians, including Gudkov, raised the alarm, attracting widespread outrage on social media and even small protests. To its critics, the measure became known as “The Scoundrels’ Law.”

Despite the concerns, only two days later the Duma voted practically unanimously in favor of the bill. Only 7 lawmakers voted against it.

“The pressure was intense,” remembers Gudkov. “It was made clear to deputies that not voting would have consequences, and that the order had come from the very top.”

It became a turning point for a parliament which gained a reputation for rubber-stamping the Kremlin’s proposals, says Schulmann.

Effective Immediately

The law was widely criticized for stripping Russian orphans — especially those with disabilities — of the opportunities the U.S. can offer. Cutting-edge medical treatments, better living conditions, quality education — privileges which, critics said, were out of reach for disabled children from remote Russian regions — are widely available in the U.S. But most importantly, those already in the process of being adopted were deprived of families they had already met and grown attached to.

“Of course if the law had been passed a little later, I would have left for the U.S. and would have gotten a great education there,” says Maxim Kargapoltsev, an orphan whose adoption by an American couple was halted by the ban. He was 14 at the time.

Now an 18-year-old college student in Chelyabinsk, Maxim was one of the Russians on whose behalf the lawsuit was filed to the ECtHR.

“I could have had a family when I needed one most. I still stay in touch with the couple who planned to adopt me — I recently visited them when I was on a holiday. But having a family at a younger age is a completely different thing,” Kargapoltsev told The Moscow Times.

Supporters of the ban argue that it has improved the lives of Russian orphans. “The attitude towards orphans and people who want to adopt has changed drastically. There was more financial support, orphanages changed the way they worked and Russian adoptions increased — despite the fact that we’re going through a financial crisis,” Yelena Afanasyeva, the very lawmaker who introduced the notorious adoption provision to the law in 2012, told The Moscow Times.

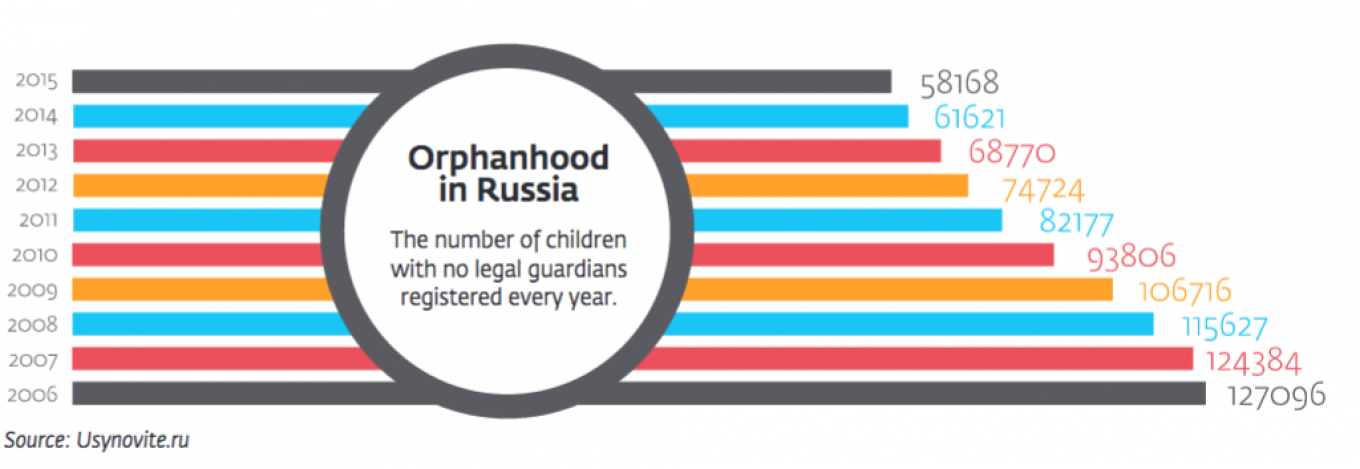

According to official government statistics, before the Yakovlev law came into force, there were almost twice as many children in orphanages than after: some 104,000 in 2012 compared to 60,100 by the end of 2015.

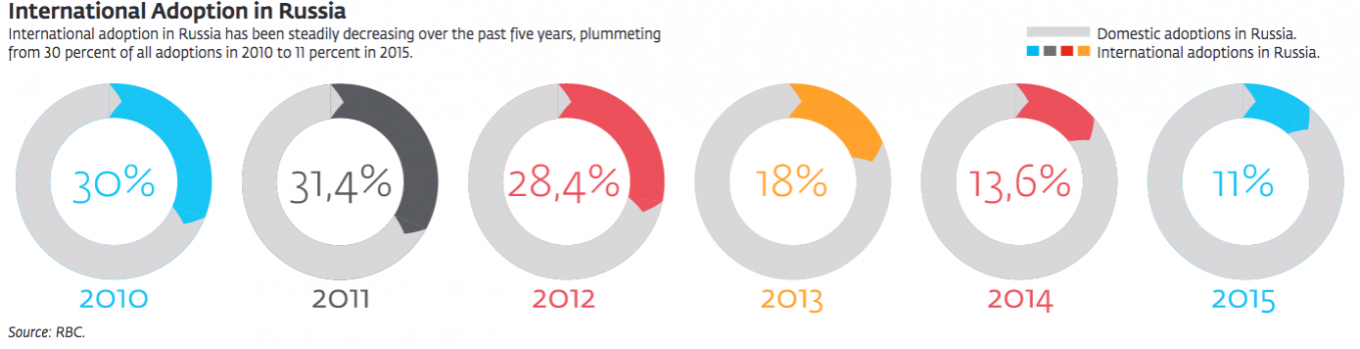

However, the number of actual adoptions has decreased: In 2012, Russian families adopted 6,500 children, whereas in 2015 that number was only 5,900. International adoption reached its lowest point last year, plummeting from 2,400 children in 2012 to 746 in 2015. At the same time, according to the office of Russia’s children’s ombudswoman Anna Kuznetsova, the number of children being returned to orphanages has increased in 2015 alone, 5,600 children were sent back to orphanages from foster families, which is 6 percent more than in 2014.

In general, lower numbers of children in orphanages does not necessarily mean that the situation has improved, says Yelena Alshanskaya, head of the Volunteers to Help Orphans charity foundation.

“Those figures can reflect a number of factors: decreased birth rates, social services taking fewer children away from families, government officials not willing to register new cases,” Alshanskaya told The Moscow Times.

Changes on the Way?

Following the ECtHR ruling, the clause banning adoption for U.S. citizens has once more become the subject of debate. For the first time in years, top officials have publicly expressed a willingness, if not reverse the law, to at least reconsider it.

Valentina Matvienko, speaker of Russia’s Federation Council, recently said Russia was prepared for “dialogue” on the law if the U.S. could “guarantee the health of Russian children.”

“This law is not a goal in itself,” she was cited as saying by Russian media.

Russian children’s rights ombudswoman Anna Kuznetsova also expressed a hesitant willingness to talk. “Our first task is to review how children who are already there are doing. If everything is fine, we can start asking what to do with the law,” she told reporters, adding that Russia’s request to follow up on children had so far been “ignored.”

Other Russian officials were not so keen to concede. Georgy Matyushkin, Russia’s representative in the ECtHR, already announced the country would appeal the ruling to the Court’s Grand Chamber. It is allowed to do so within the next three months, says Karinna Moskalenko, the lawyer who represented American families in the lawsuit.

The lawyer cautions against such a move, however. “All Grand Chamber cases go through public hearings, and nothing good will come out of drawing even more attention to this shameful legislation. It already looks very unsightly for Russia,” she said.

Matter of Political Will

Nonetheless, the statements are a careful sign that under U.S. President Donald Trump, Russia is preparing the ground for negotiations. With the Kremlin hoping sanctions targeted at Russian officials could be lifted, the Yakovlev law might become a potential negotiating tool.

“Russia does not have much to offer in such negotiations, but the Yakovlev law is something that can be bargained with,” says Solovei. He considers it unlikely that the law will be completely reversed and argues that concessions are likely to come in the form of amendments.

“Russia will never publicly say that it made a mistake or that it took inhumane action,” he says. “So if it’s partially reversed, it won’t be an act of humanity, it’ll be politically expedient.”

Even then, there are several obstacles to reversing the ban. For one, despite some protest, many Russians support the measure.

Figures by the state-run VTsIOM pollster show support for the adoption ban has steadily grown over recent years, with 76 percent of respondents in a 2015 survey supporting the law. Changing that sentiment would require a serious information campaign.

“After everything that has been said, including features on state television on Russian children being killed by Americans, reversing the mood will require a targeted propaganda effort,” says Schulmann.

Former Duma deputy Gudkov has little faith in the idea that using Yakovlev as a bargaining chip to convince the U.S. to lift sanctions will work. “Trump may be president but he is not alone; relations have to be mended with Congress and the Senate, too” he says.

Those who want the law to be lifted should look not toward the White House, but to the Kremlin, Gudkov says.

“The biggest factor is the mood of president [Putin]. Should he intend it, the law would disappear within a day.”

In the meantime, parents in the U.S. continue to hope. Not even for the opportunity to reunite with the children they once fell in love with, they say, but for the children’s well-being.

“There is no way of staying in touch with Dima and Arina, all we have is sporadic pieces of information from the Internet,” says Sara Peterson, another mother hit by the ban. She and her husband were in the process of adopting a four-year-old girl with Down syndrome and a three-year-old boy with spina bifida, a severe neurological defect, when the ban came into force. The Petersons appealed it in Russian courts but lost the case.

“They still haven’t been adopted, that much we know,” Peterson says.

“At this point, as much as we still want to take them home and care for them, we’re praying for them just to have a loving family — even if it’s not us.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.