Svetogorsk, Russia — It all began with a penis-shaped lollipop called “Mr. Bob” that appeared in a bakery in Svetogorsk, a small town on Russia’s border with Finland.

A photo of the candy appeared in social networks, where the town’s mayor — a former military man named Sergei Davydov — came across them. The indignant mayor paid a personal visit to the bakery to deliver a tongue-lashing.

“Right near the school,” he complained. “Do you even know what you are selling?”

The incensed mayor went on to proclaim: “This city does not have and will never have any gays. They won’t be allowed to come here, even from the West!” The mayor’s comments electrified social media.

While officials in neighboring cities chimed in to support Davydov’s proclamation, it represented a challenge to others: LGBT activists descended on the town to proudly declare, “gays have set foot in Svetogorsk.” Then they were arrested by for not having the requisite documents to visit a border town.

The scandal rages on—nearly 100 LGBT activists are planning two more rallies in the “city without gays.” But the story of Svetogorsk and its crusading mayor highlights the grim reality for gays in provincial Russia, where a life in the closet beats one of threats, intimidation and violence.

A city of ordinary people

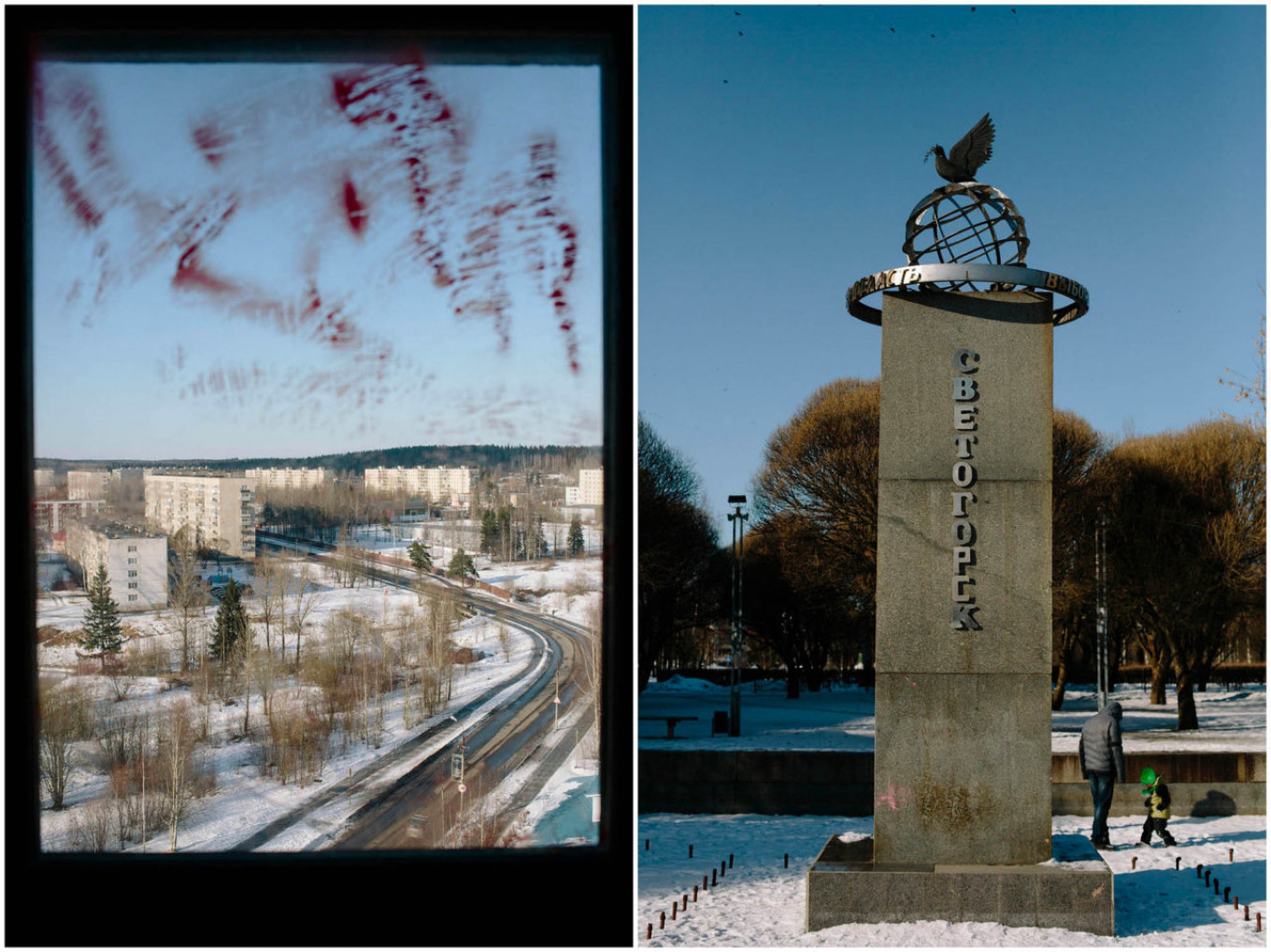

Drab concrete panel housing dominates Svetogorsk’skyline. Soviet playgrounds rust in the courtyards. There are no cinemas or nightclubs. A moss covered statue of Lenin — slowly being eroded by the elements — stands in the town’s center, a relic of a bygone era.

The town has little to offer visitors. Most Russians tourists pass through on their way to Imatra. Finns stop in just to buy cigarettes and gasoline. But locals enjoy a degree of freedom thanks to the border: Many hold multiple-entry Schengen visas that allow them to cycle into Finland for shopping and leisure.

But the border’s influence on the town seems to end there — particularly on issues of sexual morality. On March 1, Finland legalized gay marriage. Meanwhile, in Svetogorsk, gays fear for their physical safety.

Sasha is a short, slender young woman. She has green bangs and gauged ears. She always carries a rainbow ribbon, the symbol of the LGBT community. In St. Petersburg, she wears it openly. when she visits her hometown, she hides it.

She realized she was a lesbian in high school in Svetogorsk, when she fell in love with a female classmate. But she never revealed her feelings to her friend.

“That was unimaginable,” she says. “If someone had found out, I would have been beaten. Once, we walked around town holding hands and people threw stones at our backs.”

Now, Sasha lives in St. Petersburg. She returns home only rarely to visit relatives. Her sister knows about her sexual orientation, but her parents do not.

“I don’t like coming here,” Sasha says. “Within a few days I fall into depression. Last time I was here, my haircut was shorter and a guy screamed ‘faggot’ at me and cursed me to high heaven.”

Passersby do turn to gaze at Sasha — sometimes with open contempt. Looking or seeming different can be dangerous, she says, which forces gays to hide their their sexuality. Lesbians can walk in public, but gay men face greater scrutiny.

“If you’re gay, you’re toast,” Sasha says. “I would advise all gays to leave this city.”

Beating gays

Officially, Svetogorsk may have no gays, but it has plenty of addicts. With few other avenues for recreation, locals have turned to alcohol and other vices. Illegal drugs have become a serious problem.

“One in three people [in Svetogorsk] knows which drugs to buy and where to get them,” Sasha says. “But the mayor considers gays to be the main danger facing the city.”

Of the city’s limited restaurant and bar scene, the most intimidating, Sasha says, is the White Nights café, where the “cream of the city’s homophobes” gather in the evenings. She recommends the “Pizza Beer” joint instead.

It is 2 a.m. Three young men at a neighboring table down “Patriot” cocktails colored in the red, blue, and white of the Russian flag: vodka, grenadine syrup, and blue curacao. They wash it down with beer.

Asked about the mayor’s recent statement on gays, the men are dismissive.

“He’s an idiot! So what if there are gays?” says one.

“He’s embarrassing the city,” another concludes.

But not all the town’s residents are so friendly. Three young men stand drinking near a local supermarket. “[The mayor] is absolutely right!” one says. “Those faggots shouldn’t hang around here. Let them go to Finland!”

“If I see any gays around here, I’ll kick their asses,” agrees a second.

The controversy has spilled into cyberspace too. In an invitation-only social network group dedicated to Svetogorsk, a heated discussion about LGBT people rages. Residents are divided in their opinions. One writes that there are no gays in the city because “they would be [beaten] every 100 meters.” Another proposes feeding the gays to the city’s homeless dogs. Many simply laugh at the subject, relishing the controversy.

“I still have to live here”

Vadim, a homosexual resident of Svetogorsk, is afraid to leave his home. After a long conversation on social media, he finally agrees to meet in person, but asks not to be photographed. “I still have to live here,” he explains.

At 25, Vadim is a modest and polite young man. He became aware of his sexual orientation at 13. Then, his classmates began harassing and beating him because, according to Vadim, he was not like them.

“I was a quiet, stay-at-home boy. Many times I was the object of my classmates’ homophobic bullying,” he says. “I don’t even want to recall what they did to me at school.”

Before the “gay-free city” scandal, Vadim says he didn’t have a clue who the city’s leading official was. Now he knows that the mayor is “not a very intelligent person.”

“He [the mayor] should at least look at dating sites or something!” Vadim says. “He would see how many gays and lesbians in Svetogorsk are looking for partners!”

Vadim does not understand why the mayor considers him — a quiet person — a danger to the city. In his opinion, the high cost of utilities and the city’s trash-covered sidewalks are the real danger.

“I have talked with other gays in Svetogorsk through dating sites,” he says. “Butwe’re afraid to exchange photos.”

That fear is not unwarranted. They are well aware of incidents in which far right activist lure gay men into meetings through dating sites and then torture them on camera.

Vadim is convinced that the mayor’s statements have only “encouraged violence against weak and oppressed groups that already have no chance for a normal existence.”

“We don’t expect them here”

Svetogorsk Mayor Sergei Davydov, 48, has supervised the city administration since 2011. Before that, he worked as military commissar of Vyborg. He ended his military career with the rank of colonel and says he dreams of making Svetogorsk a beautiful and inviting city.

With a touch of pride, Davydov says that Svetogorsk has a social center that helps lonely pensioners and sick children, and that a charity concert raised 70,000 rubles ($1,211) to help needy families.

But the penis lollipops nullify “all of our efforts for patriotic education,” he says.

Davydov says he didn’t ban the candies. He simply went down to the store and had a conversation with the managers, who were quite surprised by the news.

“I told them: ‘If you want to sell such things, open a [sex shop].’ A person’s moral outlook is the main thing,” he says.

“If it is not prohibited by law, I have no right to prohibit it,” continues Davydov. But he admits that he is wary of homosexuals, and believes the Russian Orthodox Church advocates the proper relationship between man and woman.

Besides, gay marriages don’t produce children. Russia needs to increase its population, the mayor explains. It is therefore inadmissible to permit same-sex marriages as they do just a few kilometers away in Finland.

“Marriage between people of the same sex do not enable our state to develop and grow,” Davydov says.

That means that, under his watch, people like Sasha and Vadim will have to seek their happiness in private — or in another city entirely.

Sasha has chosen the latter. On her return to St. Petersburg, she pulls out the rainbow ribbon and pins it on her breast pocket.

“Finally, St. Petersburg!” she exclaims. “I don’t have to hide anymore!”

This is an abridged and adapted version of an article first published on the Takiedela.ru website.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.