The bullets flying at Moscow's Wildberries HQ last week are a chilling sign that Russia's wild 1990s are back with a vengeance.

In a deadly shootout straight out of a mobster's playbook, the violent chaos that once ruled the streets has returned to the Moscow boardroom, leaving two dead and the nation wondering whether Russia’s ruthless past ever really went away.

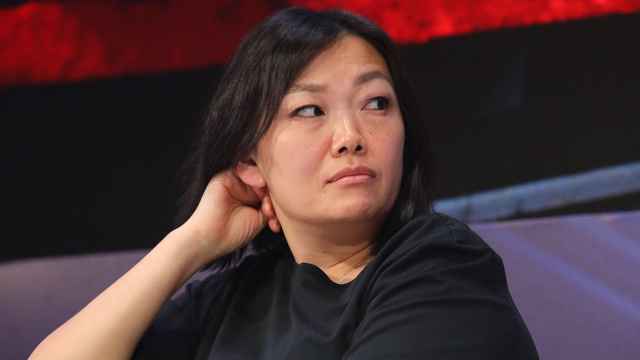

Tatiana Kim, Russia’s wealthiest woman and the founder of the e-commerce giant Wildberries, released an emotional video on Sept. 19, tearfully accusing her estranged husband Vladislav Bakalchuk of organizing an armed attack to try to seize the company by force.

“Vladislav, what are you doing?' she sobbed. “How will you look into the eyes of your parents and our children? How could you bring the situation to such absurdity?”

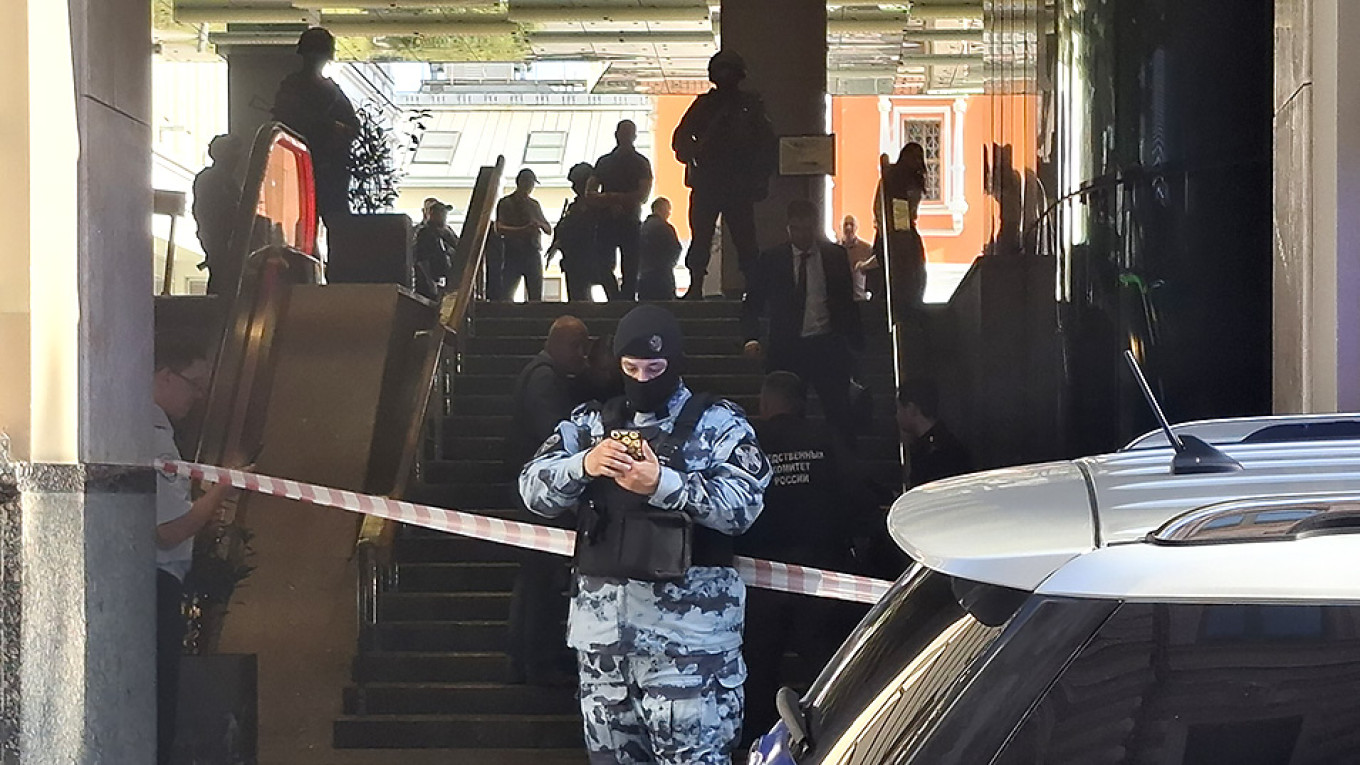

It was the worst example of corporate violence since the wild days of the 1990s. Two security guards were killed in a bloodbath, while seven others were injured as security staff faced off with the men in a dramatic showdown.

State television conveniently ignored the Wildberries shooting and the involvement of Ramzan Kadyrov, who recently met with Vladislav and pledged his support — a move widely seen as the Chechen leader’s bid to expand his influence.

Tatiana, the founder and 99% owner of the e-commerce giant Wildberries, now finds herself in a power struggle with her estranged husband, despite his minimal 1% stake in the company known as “Russia’s Amazon.”

Wildberrieswas thrown into chaos after Tatiana announced plans in July to merge with the much smaller Rus outdoor advertising company.

Analysts dismissed the deal as senseless. The independent media outlet The Bell suggested the merger may be part of Russia’s wartime redistribution of assets that has rewarded Kremlin-linked business figures. For example, the confiscated assets of French yogurt maker Danone are already being ‘sold’ to a relative of Kadyrov at a knockdown price. Similarly, Carlsberg’s Russian subsidiary is now being run by associates of President Vladimir Putin’s billionaire childhood friends Yuri Kovalchuk and Arkady Rotenberg.

The shooting incident occurred at Romanov Dvor, a premium business quarter located about 500 meters from the Kremlin. I worked in that building for seven years for Bloomberg News, which occupied the top floor. Other blue-chip tenants included Credit Suisse, Apple Inc., the law firm White & Case, the Swedish investor East Capital and the British auction house Sotheby’s.

It was a refined and elegant oasis to do business in. The building, which is owned by the Russian-Armenian billionaire Ruben Vardanyan boasted a Raiffeisen bank branch, a VIP cinema, restaurants and cafes, a French-style bakery and World Class fitness club in the basement which attracted the mistresses of many oligarchs who were chauffeured to the door.

All the European and American tenants have since departed after the invasion wiped out three decades of economic integration. Some of them have been replaced by well-known Russian companies like Wildberries and corporations from China.

The shootout brings to mind one of the most infamous events of the 1990s — the assassination of Paul Tatum, an American businessman who fell victim to the brutality of the time.

Tatum, who had co-founded a joint venture to develop and run the Radisson Slavyanskaya Hotel in Moscow, became embroiled in a bitter corporate feud with his Russian partners. His refusal to give up his share of the business led to a series of threats, and in 1996, he was gunned down near a metro station, in broad daylight.

Tatum's murder was not an isolated event. It was emblematic of a broader problem — organized crime had embedded itself within the very fabric of the burgeoning capitalist system.

Today’s Russia's economy, strained by sanctions and the ongoing war, is creating an atmosphere where business elites are increasingly willing to resort to drastic measures for survival. In the 1990s, oligarchs, criminal gangs and corrupt officials thrived in an environment where the legal system was powerless.

As the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Russia descended into a chaotic "wild east" where the rigid structures of communist central planning gave way to a lawless form of free-market capitalism.

In the chaotic 1990s and early 2000s, private militia roamed Moscow’s malls, hotels and casinos armed with submachine guns, a stark symbol of the lawlessness that gripped Russia during its post-Soviet transition.

Business disputes were settled not through negotiation, but with car bombs, contract killings, and daylight assassinations. Violence was the currency of power in a country where fortunes were built — and destroyed — by brute force, as the collapse of communism gave way to a brutal form of capitalism ruled by oligarchs and criminal syndicates.

It was an anarchic era when violence and money dictated power, and survival often depended on navigating a ruthless landscape of corruption, crime and shifting political alliances. Powerful figures hired private security forces or enlisted the protection of corrupt officials, known as krysha ("roof"), to shield their interests.

Reports in Russian media suggest authorities and business groups are considering arming guards at Moscow's 500 shopping malls, especially after 140 people were killed at the Crocus City Hall venue in March.

The capital has also recently been ravaged by arson amid fears that Moscow is returning to banditry. Chechens, who were prevalent among the armed gangs of the 1990s, are again showing their muscle amid reports that Vladislav Bakalchuk was accompanied by armed men from the republic.

As the state’s grip weakens and resources dwindle, Russia is inevitably slipping back into the violent, lawless power struggles that defined its post-Soviet years. The Wildberries shootout is more than just an isolated incident. It is a signal that the chaos of the 1990s is not in the past, but part of Russia’s recurring destiny.

The veneer of stability has cracked, exposing the same violent, lawless undercurrent that defined post-Soviet Russia. Putin is seemingly powerless to control the competing forces.

According to RBC, the Wildberries merger was signed off by Putin’s cabinet and overseen by deputy chief of staff Maxim Oreshkin. Forbes uncovered a letter in which Putin personally instructed Oreshkin to back the deal.

In reality, the wild 1990s in Russia never went away — they just went underground. The rule of law has always been shamelessly ineffectual. For the past decade, corporate shakedowns, harassment, squeeze-outs and the unlawful arrest of executives were par de course. The difference now is that the conflicts once hidden behind closed doors have come out into the open.

What has changed is the rats are no longer fighting under the Kremlin’s rug. Since the invasion of Ukraine, the power struggles have become more blatant and the rodents have emerged above the surface to fight for scraps from the table and the spoils of a shrinking economy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.