Long ago, when foreign tourist companies would send travelers to the USSR, they’d include warnings in their pamphlets to cut into Chicken Kyiv with care!

Meanwhile, Soviet citizens would usually pierce it with a fork right away to release an even flow of buttery juice.

Chicken Kyiv is famous and popular all over the world. It is served in expensive restaurants and roadside snack bars. Frozen versions are sold in supermarkets. But not every housewife dares to make it herself.

The first mention of Chicken Kyiv seems to be in the “Culinary Collection” of recipes printed in the “Journal for Hostesses” in 1913-1914. Called “Kyiv cutlets made of chicken or veal,” this early recipe called for the meat to be minced in a meat grinder, formed into patties with a piece of butter in the middle, then breaded in eggs and breadcrumbs.

These cutlets were the gastronomic calling card of the restaurant in the Kyiv hotel “Continental,” which lasted into the Soviet era. Soon these Kyiv cutlets begin to be made with a chicken fillet that was pounded thin and wrapped around a piece of butter. We find this recipe in the compilations of the 1930s. However, due to the complexity of preparation, it was not then widespread outside of expensive restaurants.

The book “Russian Cuisine: From Myth to Science” details the history of these buttery Kyiv-style cutlets. Interestingly, these cutlets also became very popular abroad. During the Russian Civil War in the early 1920s, many cooks emigrated from Ukraine to Europe and America, and they knew the secret of making what came to be called Chicken Kyiv. It was instantly popular and quickly became a standard dish on many restaurant menus.

This was a very popular dish in America in the 1930s. A former Russian Army Colonel Yaschenko opened a restaurant in Chicago called “Yar” and included these cutlets on his menu. “Col. Yaschenko, generalissimo of the Yar, is an ex-officer of the Russian Imperial Army. He recommends Russian food, especially stuffed breast of chicken Kyiv style,” wrote the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1937.

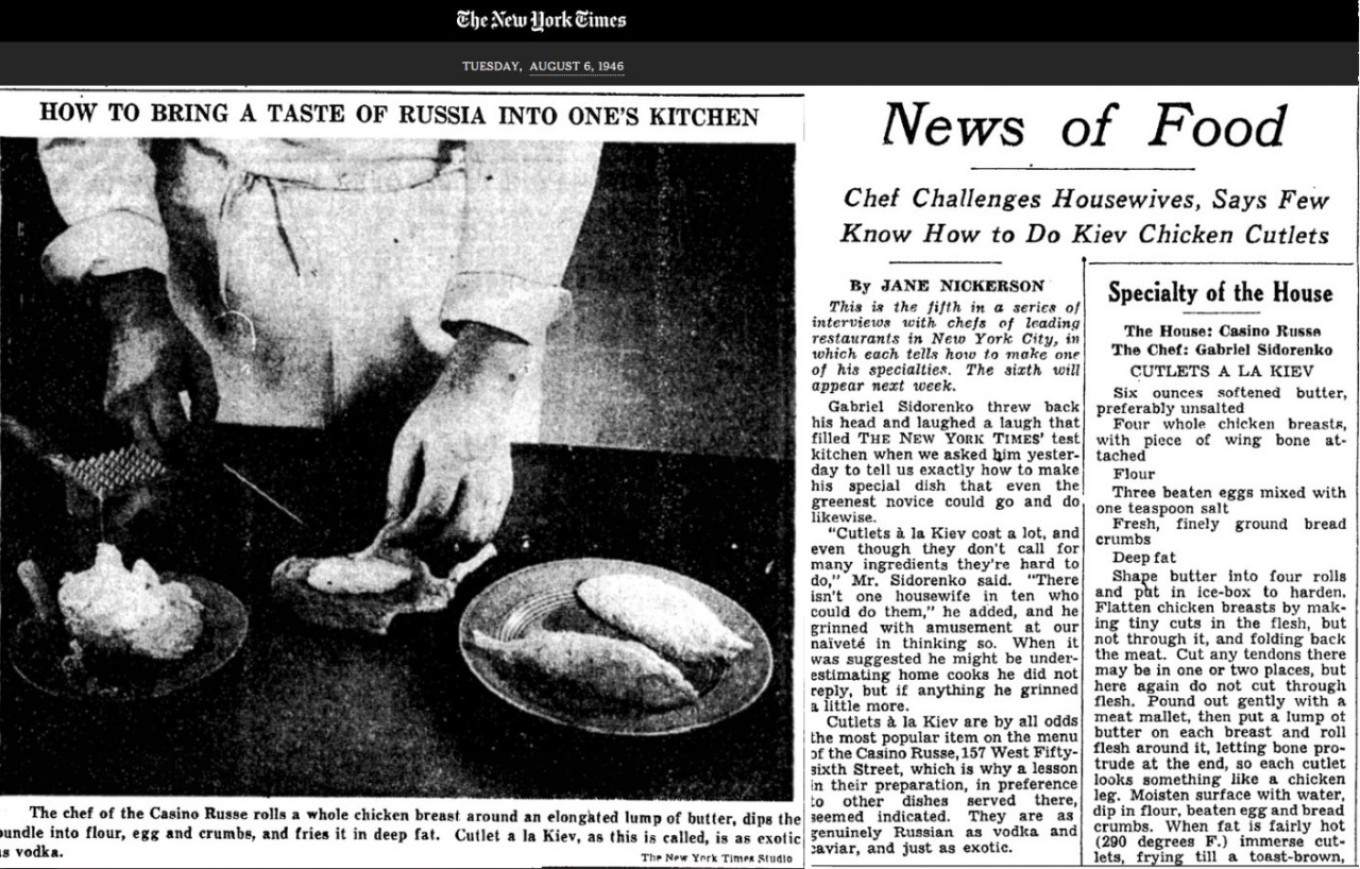

Chicken Kyiv was also served in luxury establishments in New York, such as Casino Russe. In the 1946 article in The New York Times below is a photo of “Cutlets a la Kiev — as exotic as vodka.” The Ukrainian diaspora in America took care to preserve their recipe.

With the photo is an interview with the Ukrainian chef of Casino Russe: “Gabriel Sidorenko threw back his head and laughed a laugh that filled The New York Times’ test kitchen” when asked for a recipe that even a novice could make. “There isn’t one housewife in ten who could do them,” he said, grinning. When asked if he might be underestimating their abilities, “he grinned a little more.”

Meanwhile in the USSR, this “bourgeois” cutlet was forgotten for many years — but only in cooking for the masses. In select restaurants and government dining halls these cutlets were quite common before the war. For example, they're included in a collection of recipes for cafeterias of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (the NKVD) in 1937.

But the real triumphant return of “Kyiv cutlets” to the USSR took place only in 1947. According to the cuisine researcher William Pokhlebkin, they were prepared for a small group of Ukrainian diplomats on the occasion of the return of their delegation from Paris. Soon after they appeared in one of the restaurants on Khreshchatyk in Kyiv. And ten years later the dish was included in the Intourist menu, which meant it was served in many hotels of the USSR that received foreign guests. And finally it was mentioned for the first time after the war in the monumental book “Culinary Arts” in 1955.

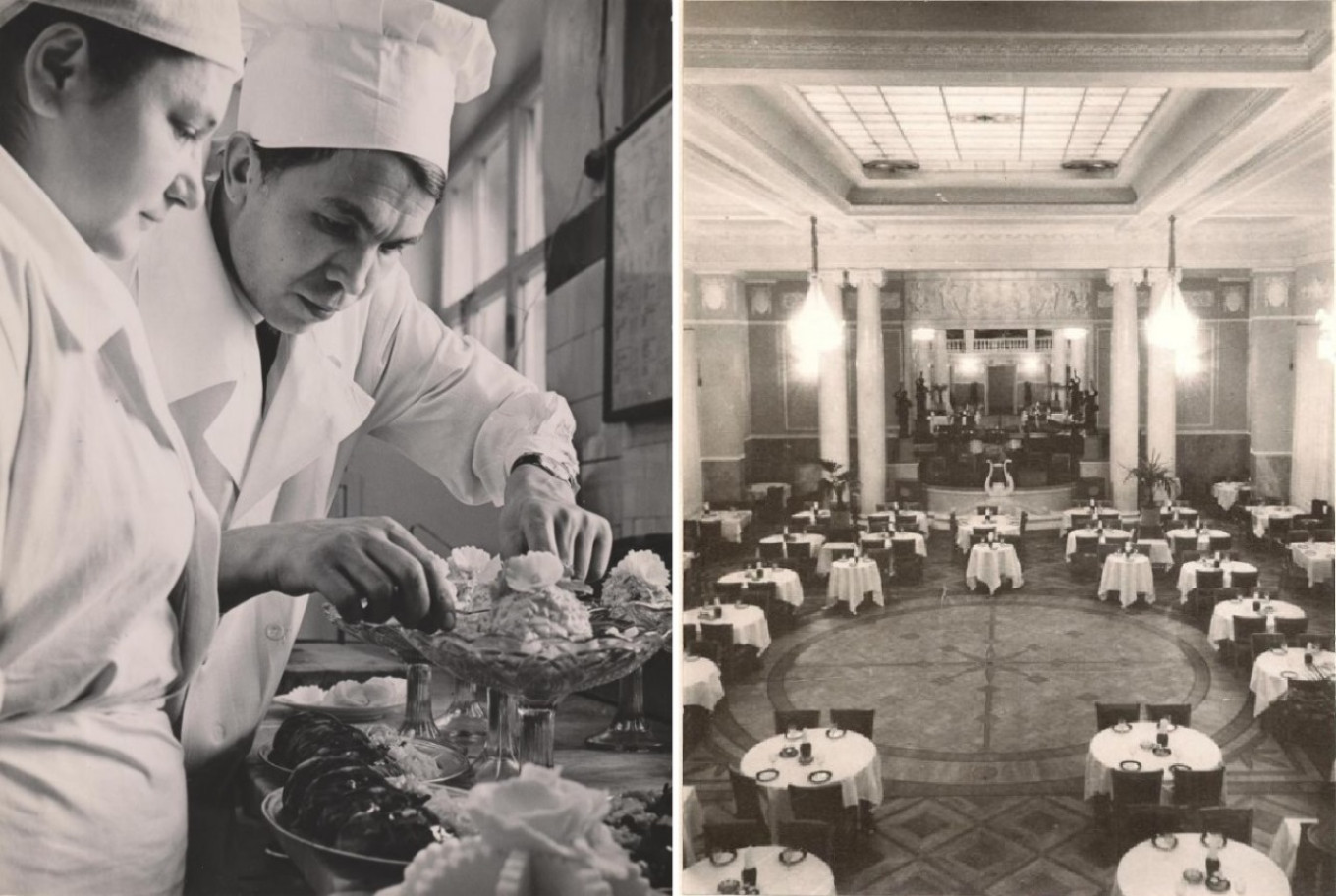

But the evolution of the Kyiv cutlet did not end there. In the 1960s and 1980s, the chef of the Leningrad restaurant “Metropol” was the distinguished Soviet cook Ali Babikov, who introduced such dishes as filet mignon, Leningrad-style stew and pike-perch au gratin, which later became the restaurant's trademark.

In the 1970s the Metropol was a strange institution. On the one hand, it wasn’t in the top category while restaurants like it in the hotels Astoria and European were three-star. On the other hand, the entire Leningrad elite ate at the Metropol, and its chefs were invited to cook for government and party banquets. Grigory Romanov, a member of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee and head of the regional party organization, was the main diner at these celebrations.

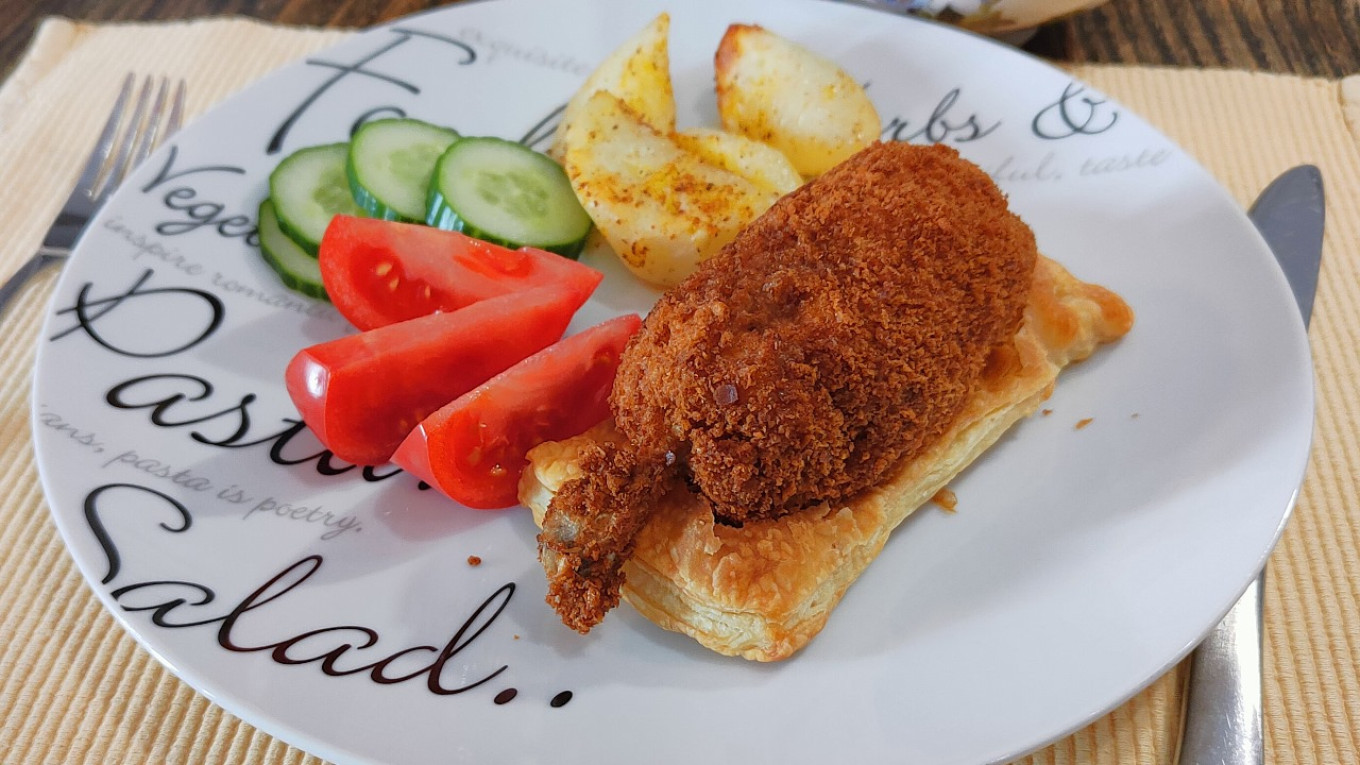

It was Ali Babikov who was able to solve the main problem of Chicken Kyiv: It is very difficult to eat. With the first slice the diner is splashed with hot butter. The Metropol cutlet (as it was known in its new incarnation) was placed in a crispy tartlet with high edges to keep the butter on the plate, not the diner.

It’s true that you need some skill to prepare Chicken Kyiv. In fact, by Soviet norms a cook could prepare 2,000 plates of pressed and grilled chicken in a shift but just a few dozen cutlets “Kyiv style.” It's almost an art.

In this recipe, we tried to make everything less complicated without compromising the best qualities of the dish. And it even has a bit of Ali Babikov’s puff pastry.

Chicken Kyiv

For 2 servings

Ingredients

- 2 skinless chicken breasts (fillet), bone in

- 60 g (4 Tbsp) butter at room temperature

- 1 lemon

- 1 bunch dill (about 40 g or 1/5 oz)

- 2 cloves garlic

- 150 ml (1/2 c) vegetable oil

- 2 chicken eggs

- salt, freshly ground black pepper

- 150 g (5 oz) breadcrumbs

- 150 g (5 oz) best quality flour

- puff pastry, baked

Before you begin cooking, watch the video below to get a better idea of the technique.

- Prepare green butter. Finely chop the dill, grate lemon zest and squeeze the juice of the lemon. Run the garlic through a press. Mix the butter, dill, zest, juice and garlic. Wrap in cling film, shape into a sausage and put in the freezer for thirty minutes.

- Divide the chicken breast into a large fillet with bone and a small fillet.

- Cover both fillets with cling film and pound the meat with the smooth side of a mallet. Try to keep the thickness of the fillets even and the edges thin; this will hold shut the edge of the cutlet better.

- Take the prepared butter out of the refrigerator and cut in half (or according to the size of the fillet).

- Salt and pepper the fillets. Put a piece of green butter in the middle of the large fillet with the bone, put the small fillet on the butter and cover with the edges of the large fillet. Press together and shape the cutlet into an oval.

- Prepare the batter. Break the eggs into a small bowl and mix thoroughly with a fork. To make the batter homogeneous, pour it through a strainer.

- Roll the cutlet in flour, dip it in the batter and then in breadcrumbs. Dip once more in the batter and then in breadcrumbs for a thick, crispy crust. Place cutlets in the refrigerator for 10-15 minutes.

- Preheat the oven to 180°C /355°F.

- Pour vegetable oil into a wide pan (sauté pan), heat the pan and deep-fry cutlets until golden.

- Transfer the cutlets from the pan to a baking dish and put in the oven for 10 minutes.

- When serving, put the cutlet on a piece puff pastry (made without yeast) baked in advance so that the tasty butter does not get lost on the plate.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.