“Stop sinking and think of your income, my star. Overseas you're going to rot in a stinking backyard. No one needs your English single in the Anglophone world.”

These are the lyrics of “Kalinka,” the first English-language track by popular rapper-in-exile Noize MC. The song captures the struggles of the many Russian artists, musicians and comedians who left the country and are trying to find relevance with audiences in Europe.

As newcomers, they face tough competition with Western artists who are long-established on the scene. And a choice with no right answer: to switch to English, or keep performing in Russian?

Many, like Noize MC, have switched to English, though the rapper worries in “Kalinka’s” lyrics that he may never be popular in the “Anglophone world.”

“Kalinka” is set to the music of the Russian folk song of the same name to invoke nostalgia for the homeland, an ironic contrast with the artist’s real-life experience in Russia.

In December 2021, Putin’s government launched an investigation into Noize MC’s lyrics for “extremism” after he wrote a sarcastic social media post. The rapper left Russia and was given a humanitarian visa in Lithuania with his family in early 2022.

Speaking to The Moscow Times over the Telegram messaging app, Noize MC, whose real name is Ivan Alekseyev, said he’s aiming to reach more international listeners as well as his core audience of emigre Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The challenge, he said, is to “stay connected to my roots” while writing more songs in English to “share my message globally.”

This message is a political one.

“Music is a powerful tool for raising awareness and inspiring change, and I believe it’s crucial to use my platform to speak out against oppression and support those who are fighting for their rights,” Noize MC said.

He’s also keen to distract those whose lives “have been turned upside down and will never be the same, to focus on reflecting who we are, what cultural significance we carry for our country while being away from home and what cultural legacy we can leave behind.”

The linguistic challenge is most acute for stand-up comedians: Denis Chuzhoi, a comedian based in Berlin, shares his struggles of how to be funny in English compared to his native Russian, as well as everyday migration concerns.

“What if I was cheated at uni and my English isn’t real? Are people laughing at me just because I sound like the town madman?”, he wrote on X (formerly Twitter) after one of his performances.

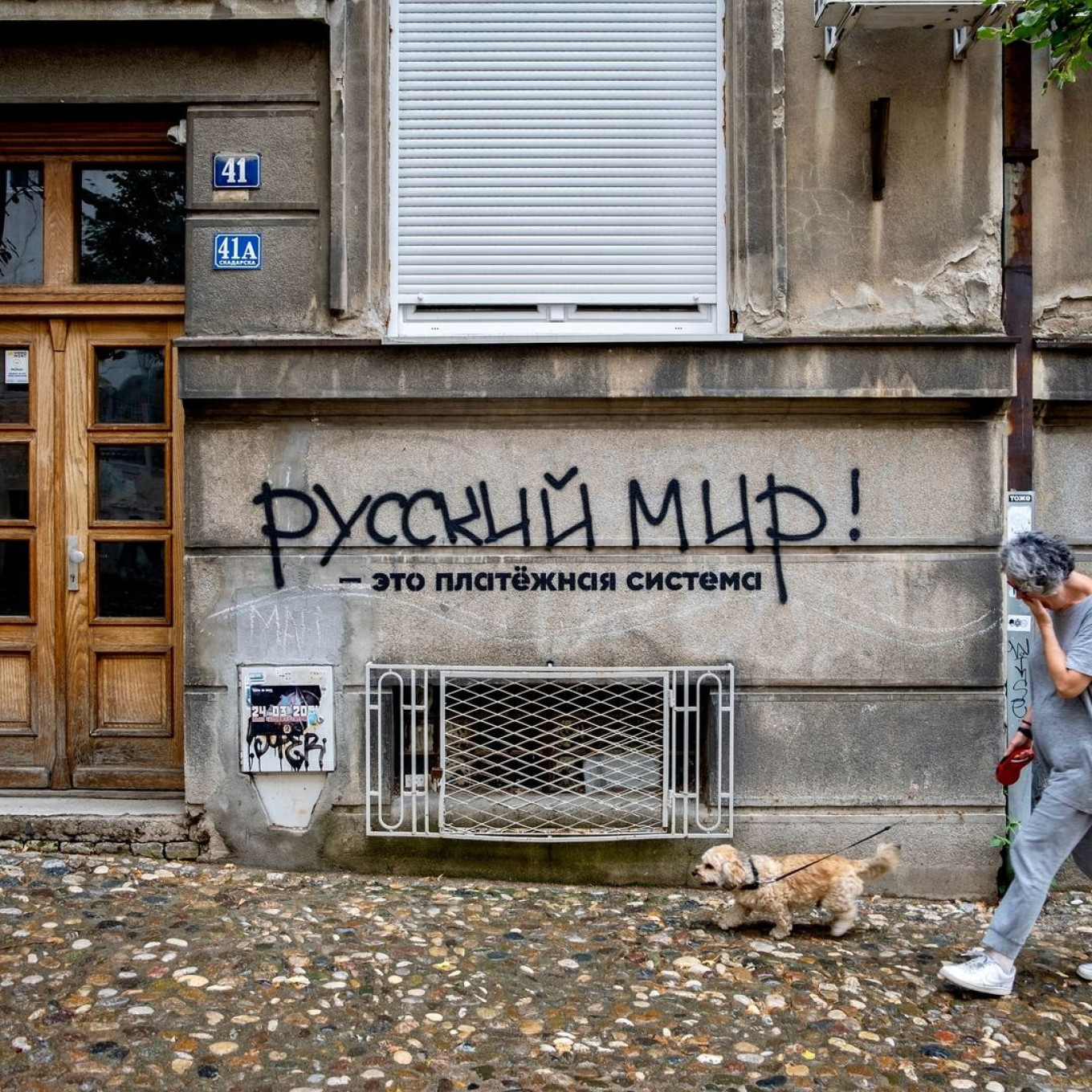

Other artists continue to work in their native language, such as street artist Andrey Toje, who creates works in Russian in his new home in Serbia. Most recently, he covered pro-war Z symbols often found on Belgrade’s streets with glass and the instructions “Break glass in case of emergency.”

Toje said his creativity vanished for a year after he moved to Serbia in 2022.

“I had used up all my ideas in Russia and I was just focused on survival, sleeping on friends' sofas with only a towel,” he said.

In time, he found the motivation to continue making art aimed at Russian audiences, primarily about the war.

“The topic is still current and we shouldn’t forget about it. I can’t make something funny while this is still going on,” Toje said.

“My motivation is to create dialogue between Russian speakers here. Maybe they take pictures and share it. The topic is negative, but people when they see it, they often smile. Instead of making you hate, it makes you feel positive,” he continued.

The challenge is whether the diaspora, now largely tired of the topic of war and focusing on their lives as migrants, will pay attention.

In contrast, Ploho, a Siberian post-punk band known for their low voices and masterful guitar work, left Russia in 2022 and is now touring Europe in a bid to attract new audiences.

Leaving home changed the band’s music.

Ploho frontman Viktor Uzhakov said: “Life in Novosibirsk was a depression in itself and this was reflected in our songs. Now our music is less depressing … [it’s] more about love and social issues.”

However, they plan to continue performing and writing in Russian.

Uzhakov, who ran the Void music festival in the city of Novosibirsk until it was raided by the police in 2016, said: “To write songs in another language, you need to be able to think and live in it. This is unfortunately not my case.”

He once experimented with a German recording of his song and said he might do so again, but it’s not easy.

Despite the language barrier, Uzhakov sees plenty of locals at his European gigs in addition to the Russian diaspora.

At the same time, it remains difficult for the band to gauge its success.

“The halls that are provided to us are most often full and they don’t throw rotten tomatoes at us…which is something, at least,” he said.

Throughout 2022, Ploho's European gigs, like many other Russian artists, were canceled as venues chose to support Ukraine, despite the band’s anti-war stance.

Touring is slowly returning to normal. “Gradually, European countries realized that we are not terrorists or maniacs and have not occupied anyone’s lands. We're just a band that plays music and we want to keep doing it,” Uzhakov said.

Though visa restrictions are a growing obstacle, Uzhakov said that “living in Russia, you get used to difficulties.”

Artist programs in France and Germany have been the most supportive of Russian exiles. Ploho will obtain an artist’s visa in France, giving them residency. Toje, meanwhile, is hoping to stay long-term in Belgrade, where an estimated 300,000 fellow Russians live.

Neither Uzhakov of Ploho nor Toje had planned to move abroad before the war.

Uzhakov said that although he likes the people and structure of European society, he admits he will never become part of it.

“I am not the kind of person who is ready to assimilate in another country, in another language and culture,” he said. “I never planned this and now it is a necessary measure — not the romance of moving to Europe.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.