Despite the EU's partial embargo on Russian oil and some European countries' ban on Russian gas purchases, the Kremlin’s fossil fuel revenues show resilience, prompting further soul-searching among Ukraine’s allies on the future course of action.

Russia weathers the sanctions storm

Over two years into the invasion of Ukraine, sanctioning Russia's energy sector — the Kremlin's main cash cow — remains an elusive task for the Western coalition.

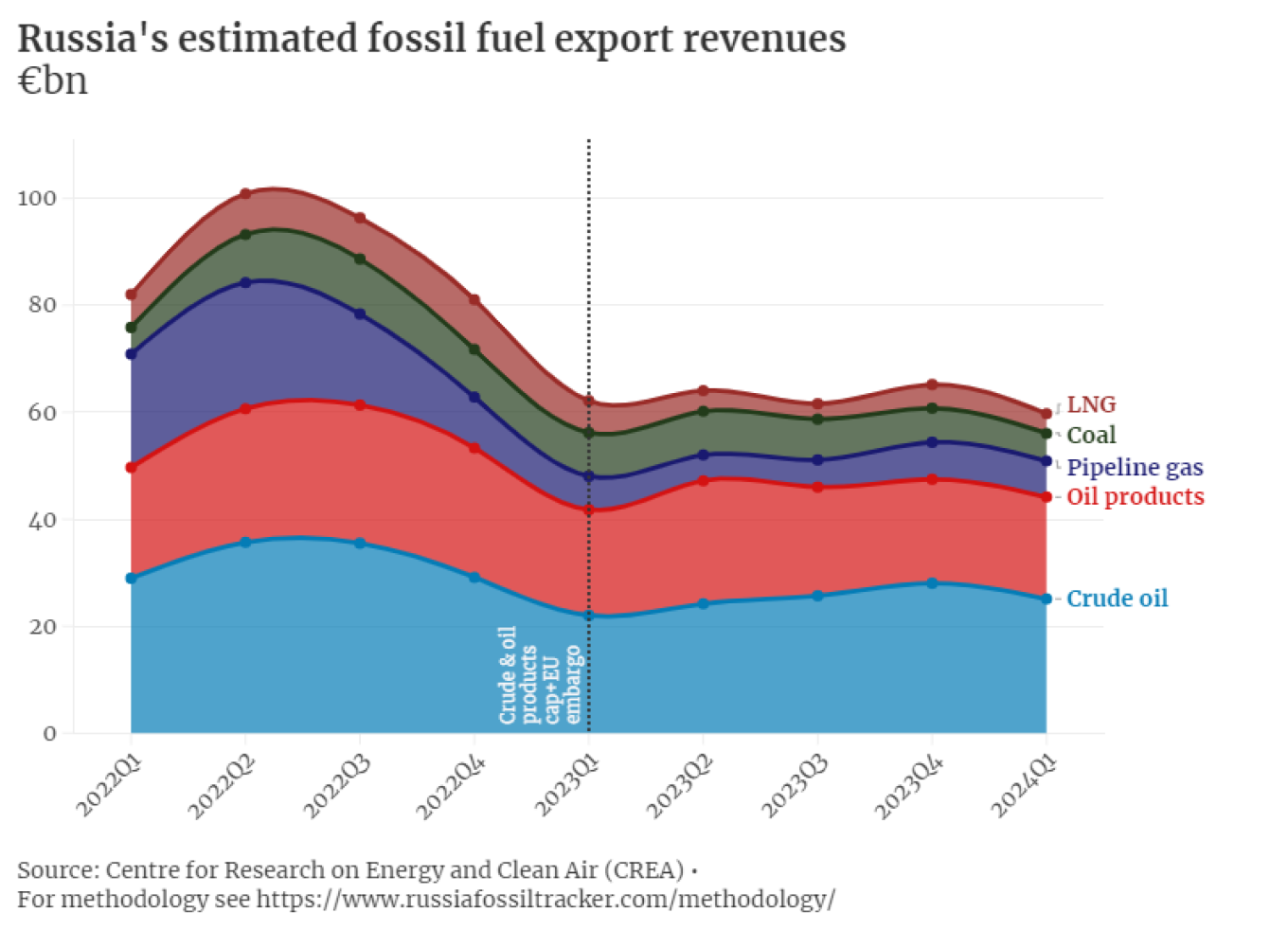

In June alone, Russia sold fossil fuels — which include oil products, gas and coal — worth over 20 billion euros ($21.8 billion) or 664 million euros ($726 million) a day, according to the data from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) think tank.

This volume is not as high as during 2022, when gas and oil supplies were even tighter and the anticipation of Western sanctions made consumers anxious to buy more, but it is still enough to keep its war machine running.

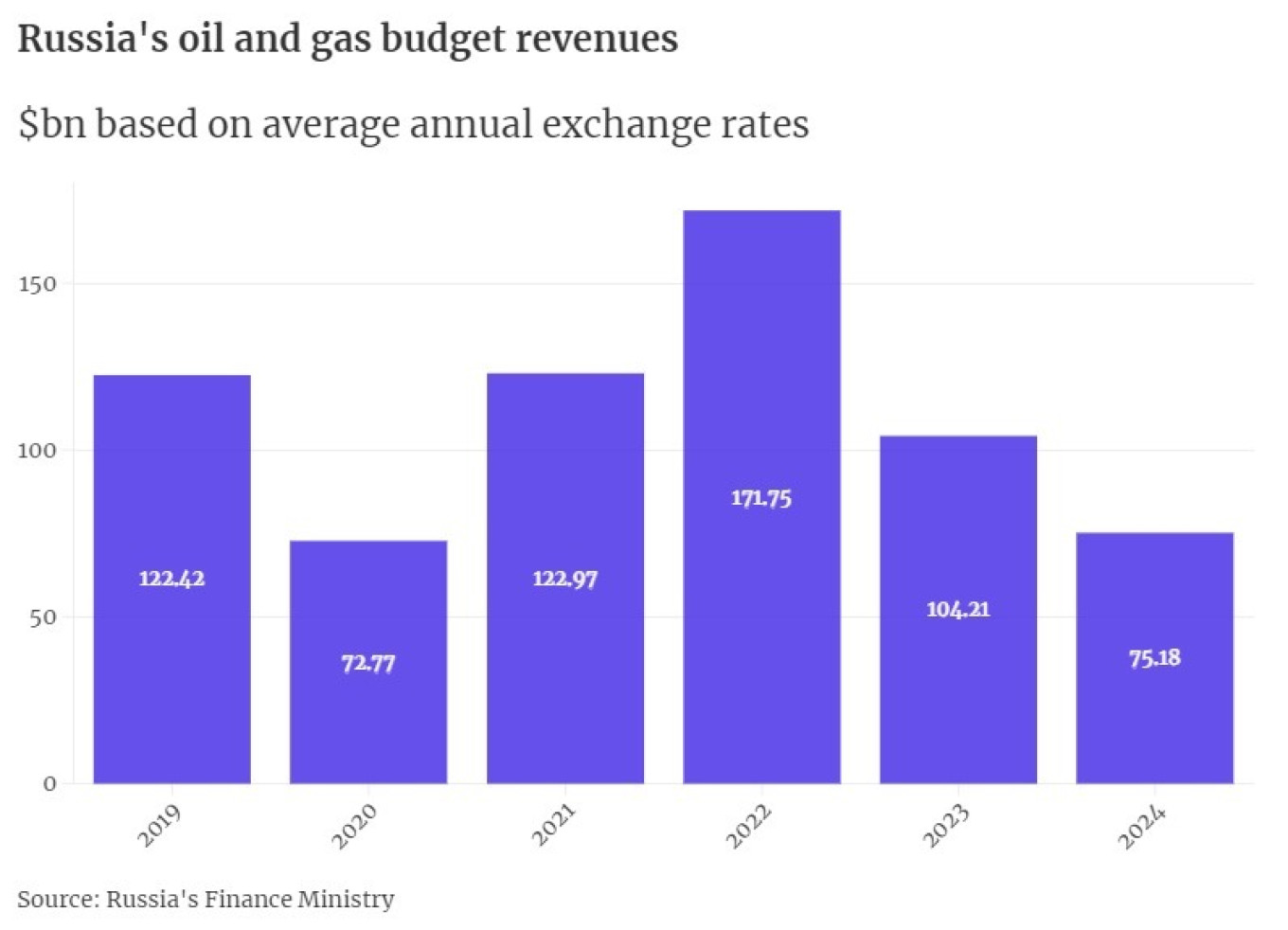

Russia’s overall oil and gas budgetary intake remained stable throughout 2023, with revenues increasing by 61% year-on-year in the first seven months of 2024.

Some rebalancing has taken place, of course.

Moscow's post-war gas revenues have shrunk due to the closure of the Nord Stream pipelines and a reduction in EU imports. Its oil exports have proved more resilient, however, and now account for 60% of the country's fossil fuel revenues.

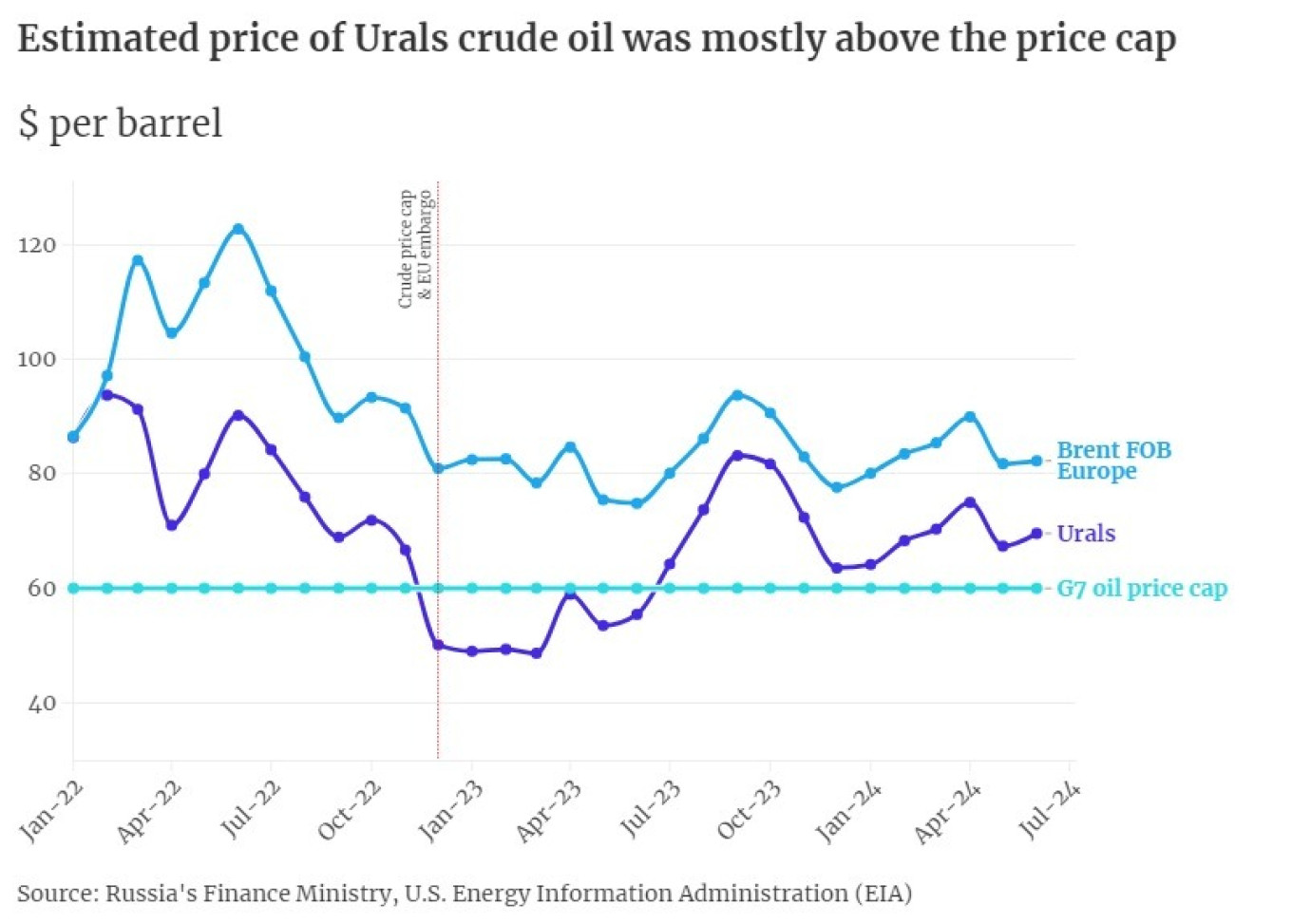

Western attempts to go after Moscow's oil revenues by denying services to all trades involving Russian oil at more than $60 a barrel have not dramatically changed the situation.

To circumvent the cap, Russia has used a so-called "shadow fleet,” estimated at between 435 and over 1,000 vessels, which operate without recourse to Western services.

As a result, Russian oil consistently sells above the $60 cap, albeit for the first few months of early 2023, and the discounts Moscow offers to India and China diminished by the end of 2023.

Some analysts, such as energy analyst Sergei Vakulenko, have suggested that Russia could actually be selling oil to China or India for more than the estimated Urals price in the opaque post-sanctions market.

Moscow is now looking to apply the same playbook to its trade in liquefied natural gas (LNG).

According to the Financial Times, Russian-linked companies have reportedly purchased “dozens of ships” capable of carrying LNG over the past year. In its Aug. 5 report, Bloomberg has identified one such suspected vessel docking at the U.S.-sanctioned Arctic LNG 2 export facility.

While the EU has not imposed an outright ban on Russian gas deliveries, further restrictions such as an LNG price cap are being touted by analysts as possible options.

Counting the costs

That's not to say that Western restrictions have gone unnoticed by Russia.

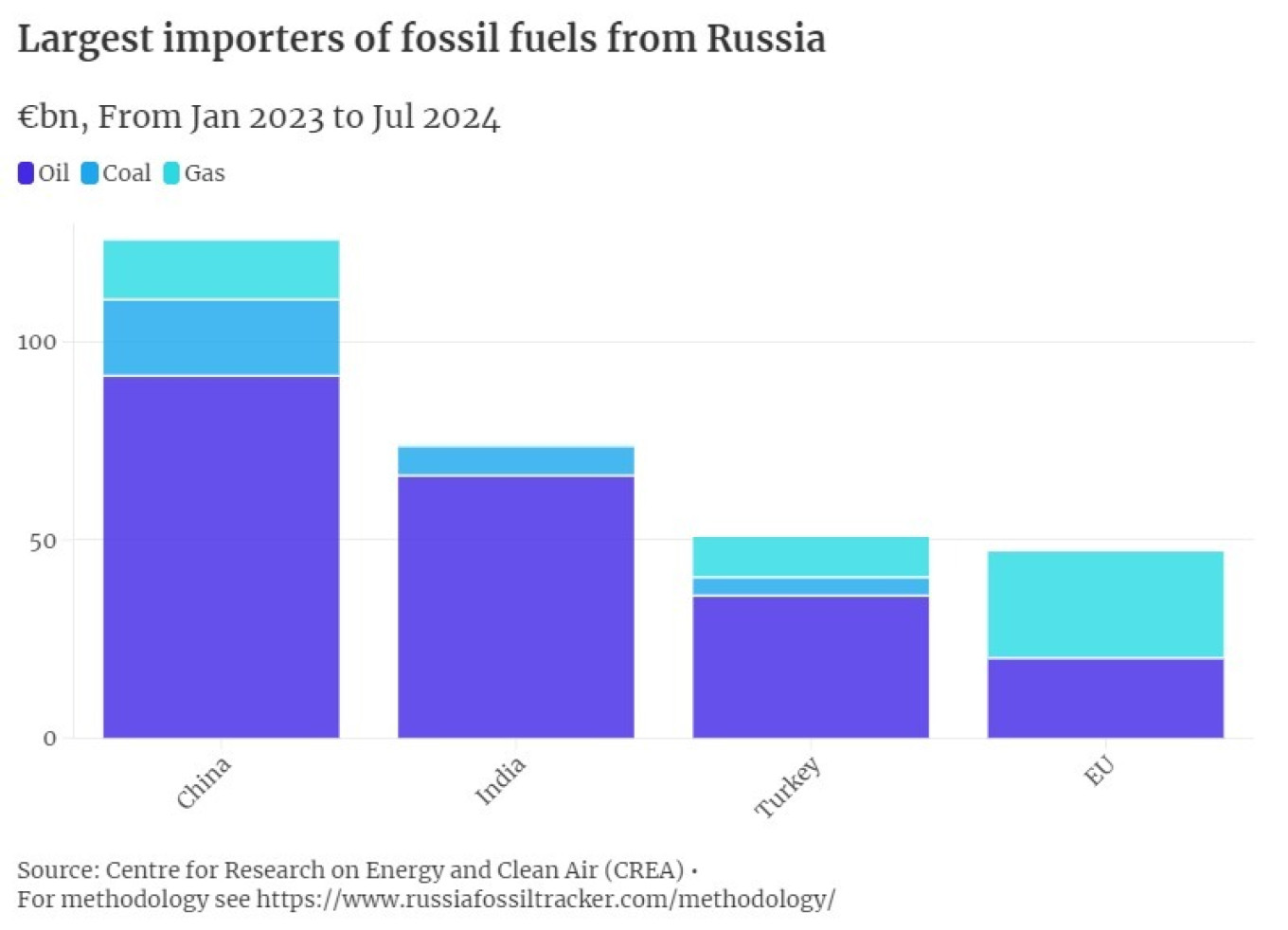

First, Moscow had to offer discounts to its new oil customers in Asia, who had gained new market power as Russia's main customers after the partial European embargo and price cap.

However, the range of discounts offered by Russia to China and India varies according to market conditions.

For example, according to a May report by India's Financial Express, discounts on Russian oil compared to global price declined to 8% in the period of September 2023 and February 2024, down from 23% in April-August 2023.

CREA put the price tag at 34 billion euros ($37.2 billion) in lost export revenue for Russia for the whole of 2023 compared to a situation with no restrictions. This is about 14% of Russia's estimated oil revenues for 2023.

The analysts said the figure reflects the lost export revenue for Russia, which had to sell oil cheaper under the oil cap, especially in the first quarter of 2023.

Second, Russia's netback from energy sales is reduced by the sheer cost of rerouting supplies away from Europe and the procurement of a shadow fleet.

The Bell estimated Russia’s expenses on the shadow fleet and losses at over $11 billion as of November 2023. The sum included $2.3 billion in expenses on the tanker fleet and another $9 billion on alternative insurance arrangements for vessels in the wake of the Western-backed oil price cap.

In its June paper, the Kyiv School of Economics estimated Russia’s spending on the shadow fleet at a higher $8.5 billion.

Third, restrictions on Russia's access to Western technology and services have created additional hurdles.

For example, Novatek, Russia's largest LNG producer, faced repeated problems with the construction of its Arctic LNG 2 plant due to sanctions pressure from the U.S.

Straddling the middle ground

For advocates of a tougher approach to Russia, the West's current sanctions policy framework is inadequate.

However, it is difficult to find a silver bullet that would finally cripple Russia's energy sector without negative consequences for the West.

Improving the compliance of existing restrictions is a costly and complicated process.

A total of 53 vessels linked to transporting Russian oil have been sanctioned by the West between October 2023 and July 2024, Bloomberg reported.

Such sanctions designations help stem the flow of Russian oil, but there is a limit to that, George Voloshin, a global anti-financial crime expert at the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS), told The Moscow Times.

On average, Western countries designate only about 10-20 every few months, while Russia's shadow fleet can number up to 1,500 or even 2,000 ships, Voloshin explained.

“This means that at the current pace, Russia can add more ships to its global shadow fleet than the number of ships sanctioned in each successive round of designations,” he said.

Some argue that a more radical escalation of the energy war is needed.

Stepping up pressure on third countries that trade with Russia — or even an outright blockade of Russia's access to the Baltic Sea, through which some of its energy exports pass — have been mooted as possible ways of disrupting Russia’s supplies.

But these steps are not without repercussions.

Most pertinently, radical restrictions on the acceptance or facilitation of Russian oil cargoes might limit the energy supply on the world market and, consequently, spur global inflation, which would also affect the West, Voloshin said.

As for Estonia’s proposal to blockade the Baltic Sea for Russia, experts say this would put Moscow on the brink of military confrontation with NATO.

According to oil analyst Sergei Vakulenko, attempts to stop the “physical flow of Russian oil through international straits would amount to a blockade, and will be seen as such.”

The blockade would amount to a casus belli and is only possible in a war scenario such as Russia declaring war on NATO or vice versa, agrees Voloshin, adding that freedom of commercial navigation through the Danish Straits is recognized under the 1857 Copenhagen Convention.

Just as the invasion of Ukraine has evolved into a war of attrition, Western sanctions no longer resemble a blitz of novel measures, but a progressive refinement of the current gradual "middle ground" approach to limiting Russia's profits without jeopardizing global economic stability.

While the crippling destruction of Russia's energy exports may seem a distant goal, imposing additional costs on the Kremlin and chipping away at its market power is still realistic in the long term if there is a political will for a more patient approach.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.