The United States famously does not negotiate with terrorists. But it has shown willingness on multiple occasions to sit down with enemy states to negotiate the release of both American and foreign nationals, even giving up people who threatened their own national security in return.

This latest prisoner exchange, which includes a total of 24 people from seven countries, is the largest to take place since the Cold War.

The most recent prisoner swap took place in December 2022, when the U.S. exchanged Brittney Griner for Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout. Basketball star Griner, a two-time Olympic gold medalist, was arrested in Moscow on drug trafficking charges for carrying e-cigarette cartridges containing less than one gram of cannabis oil.

Despite efforts from Washington to include former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan in the deal, Moscow did not release him until this year because they did not view Bout to be a valuable enough prisoner.

Despite efforts from Washington to include former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan in the deal, Moscow did not release him because they did not view Bout to be a valuable enough prisoner.

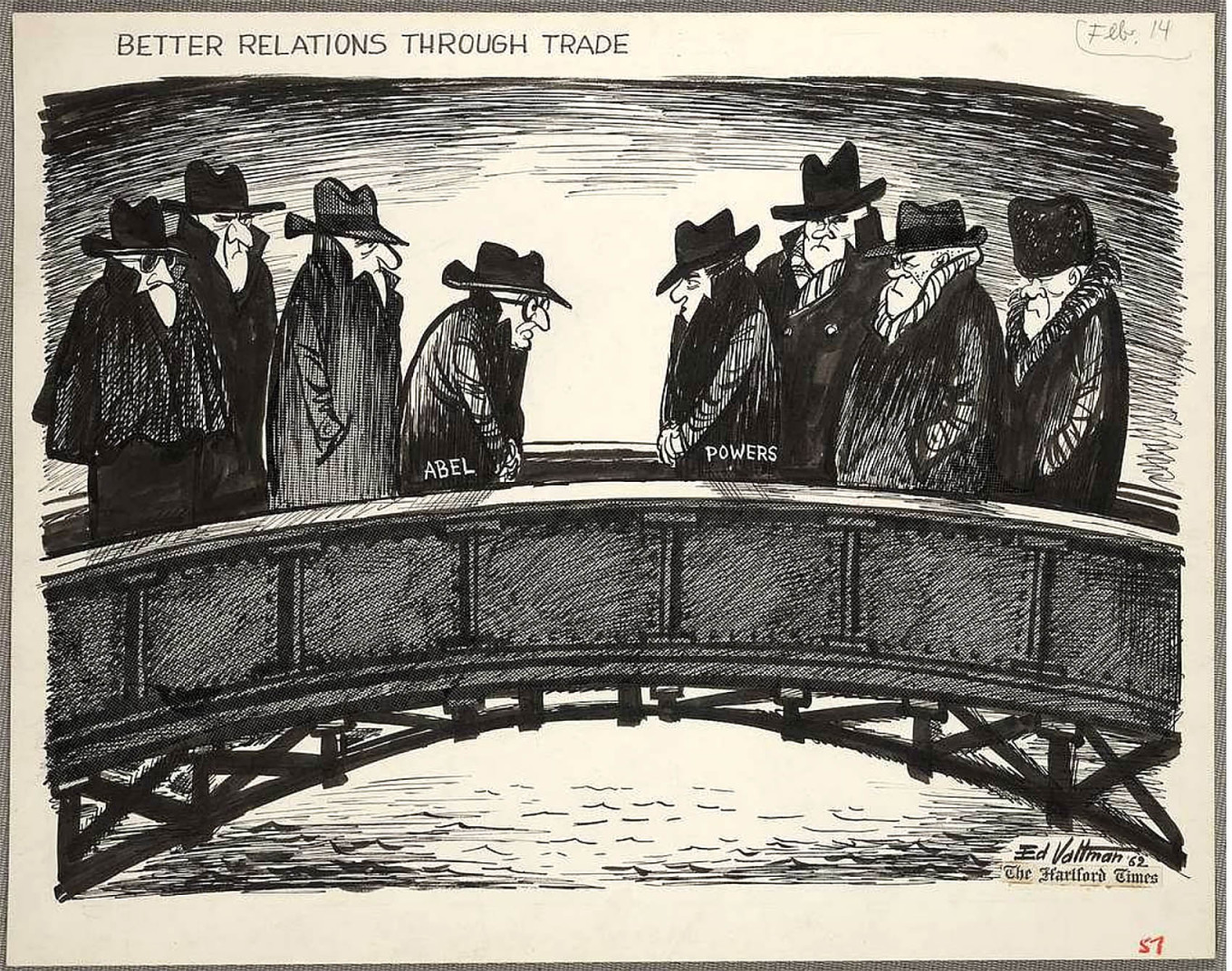

Prisoner swaps took place regularly between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1962, Soviet Colonel Rudof Abel — a senior KGB officer caught spying in the U.S. — was traded for American spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers on the Glienicker bridge linking East and West Germany.

Twenty-three years later, on the same bridge, the U.S. released four agents from Warsaw Pact countries in return for 23 Westerners jailed for espionage.

In 2010, 10 Russian sleeper agents from what was dubbed the “Illegals Program” apprehended in the U.S. were exchanged for four Russian nationals, three of whom were serving sentences for “high treason” against the Kremlin.

One of the prisoners released by Russia was Sergei Skripal, a GRU colonel who worked as a double agent for British intelligence. After moving to Britain following his release, Skripal and his daughter Yulia survived an assassination attempt using a nerve agent. British authorities and an investigation by Bellingcat found the attack was carried out by Russian nationals. The Kremlin denies giving the order.

The 2024 prisoner exchange is marked not only by its scale, but by the professions of the prisoners on both sides. While Russia historically handed over Western nationals, the people released this time are journalists, human rights defenders, democratic thinkers and political prisoners who do not have the same international name recognition as Evan Gershkovich or Vladimir Kara-Murza.

The people President Vladimir Putin welcomed back to Russia, in contrast, were spies, hackers, and even a hitman. Putin had long hinted that high-profile prisoners — even including the late opposition figure Alexei Navalny — could only be released if the Germans gave up Vadim Krasikov, who was given a life sentence in 2019 for assassinating a former Chechen rebel in central Berlin. Putin embraced Krasikov after he stepped on the tarmac.

Upon arrival in the United States on Thursday night, Gershkovich told the media he hoped more political prisoners could be released from Russia.

“I spent a month in prison in Yekaterinburg where everyone I sat with was a political prisoner. Nobody knows them publicly, they have various political beliefs, they are not all connected with Navalny supporters, who everyone knows about. I would potentially like to see if we could do something about them as well. I’d like to talk to people about that in the next weeks and months,” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.