The leader of Russia’s notorious Wagner mercenary group who served nine years in prison for theft, interfered in U.S. elections and has been accused of war crimes in Ukraine is not someone usually associated with children’s literature.

Yet almost 20 years ago, Yevgeny Prigozhin — commonly known as “Putin’s chef” because he rose to prominence by providing catering services to the Russian president — penned a playful children’s story.

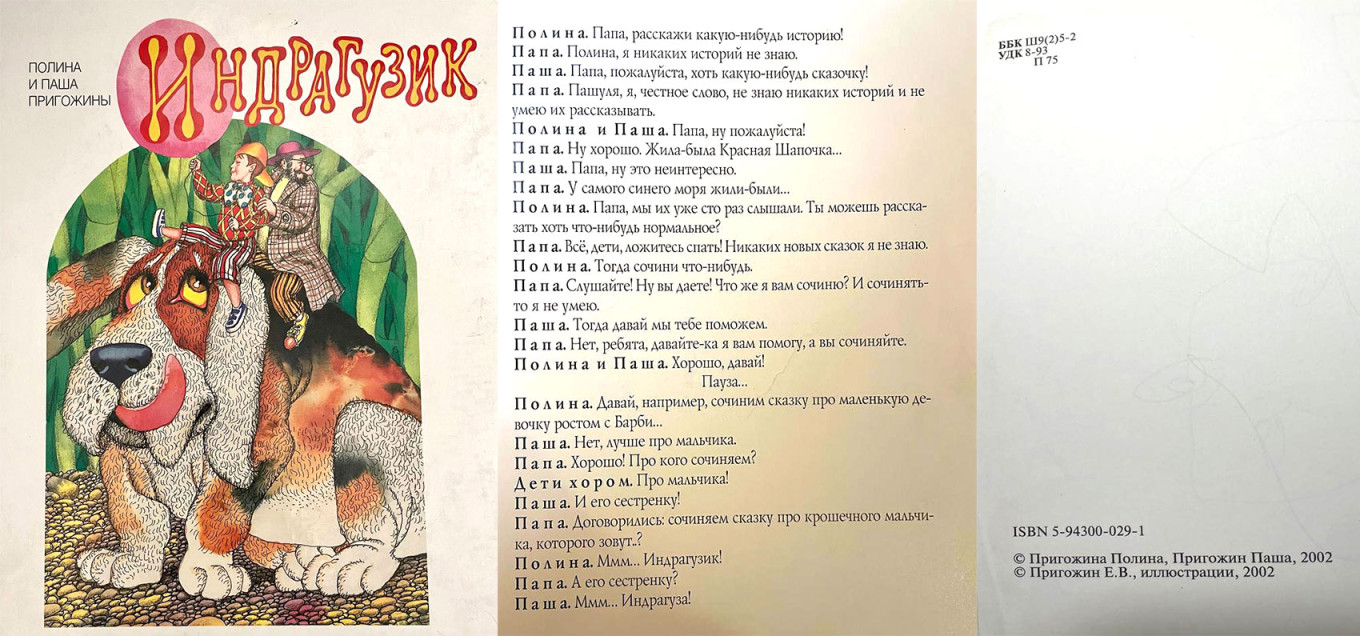

With the title “Indraguzik,” a made-up name, the book tells the tale of a little boy and his sister who live with their family inside a huge theater chandelier.

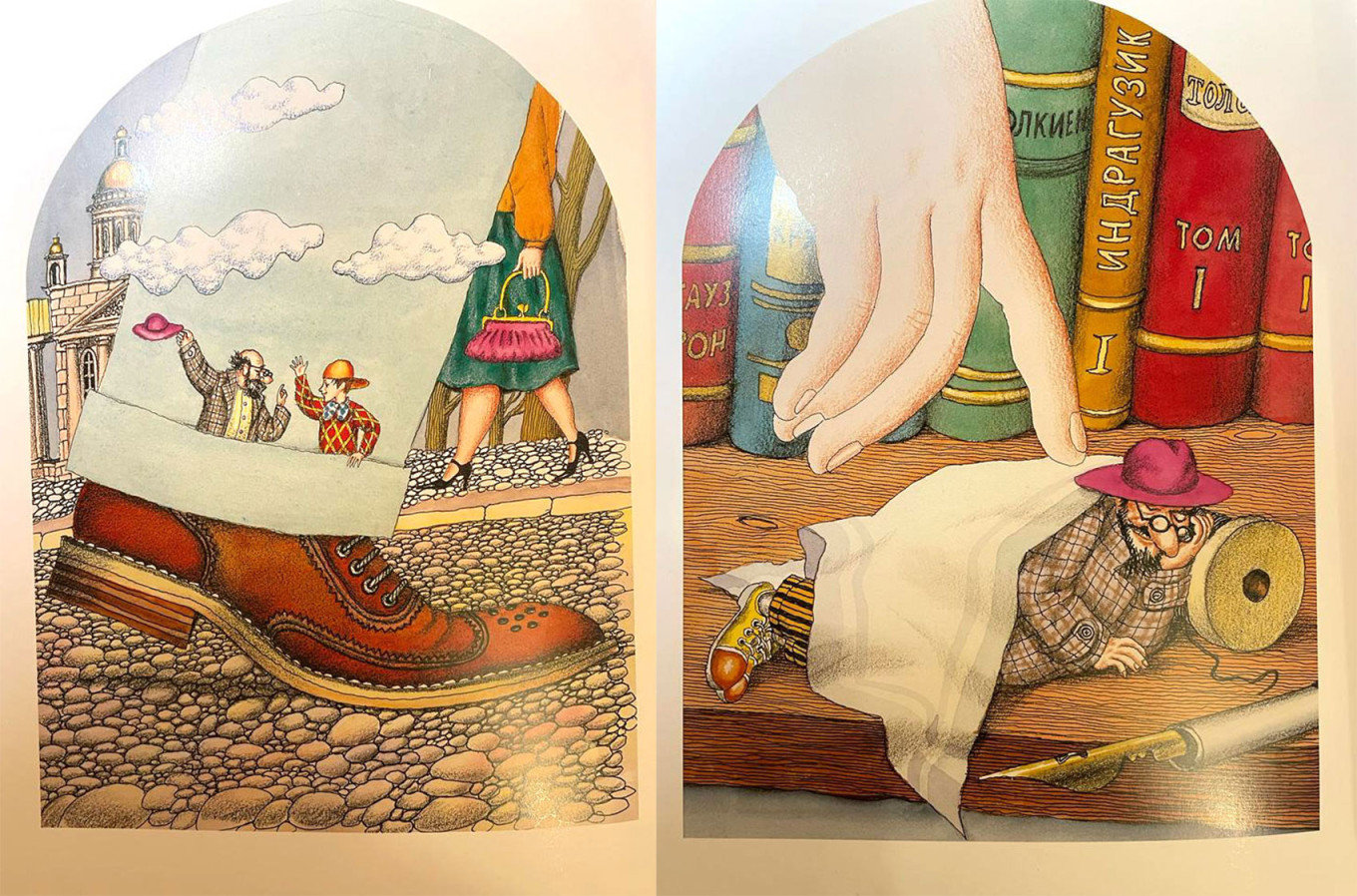

Officially, the authors of “Indraguzik” are Prigozhin’s two children, Polina and Pavel. However, the preface of the book, of which just 2,000 copies were printed, states that the story was a collaboration between Prigozhin, his son and daughter.

The Moscow Times acquired a surviving copy of “Indraguzik,” which sheds unusual light on a man best known today for his bloody tactics in Ukraine, feuds with top Russian generals and — some speculate — political ambitions.

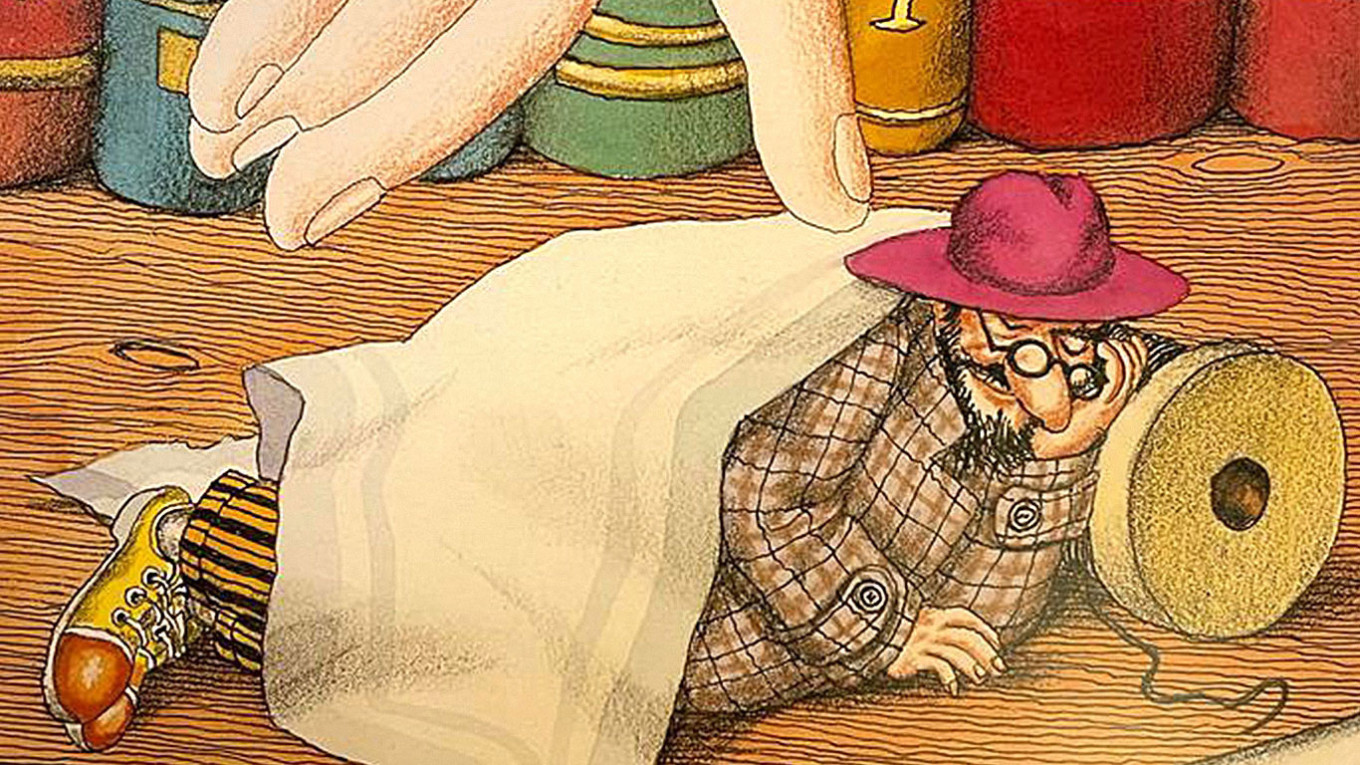

The story itself is set in a land of “small people” who live among ordinary humans and follows Indraguzik as he falls from a theater chandelier and tries to find his way home.

According to the book’s preface, Polina and Pavel suggested the names for the main characters and persuaded their father “to invent a story about a tiny boy named Indraguzik and his sister Indraguza.”

Prigozhin’s Wagner Group recently claimed to have captured the Ukrainian city of Bakhmut after months of bloody fighting that cost tens of thousands of lives.

In an interview early this month, Prigozhin, 62, bitterly criticized Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and other top officials, warning of a 1917-style revolution if the Russian elite does not throw its full weight behind the war in Ukraine.

When “Indraguzik” was published by little-known publisher Agat in 2004, Prigozhin — who spent nine years in prison on theft charges in the 1980s — was running a successful restaurant business in St. Petersburg.

His clients included Putin and other future political heavyweights.

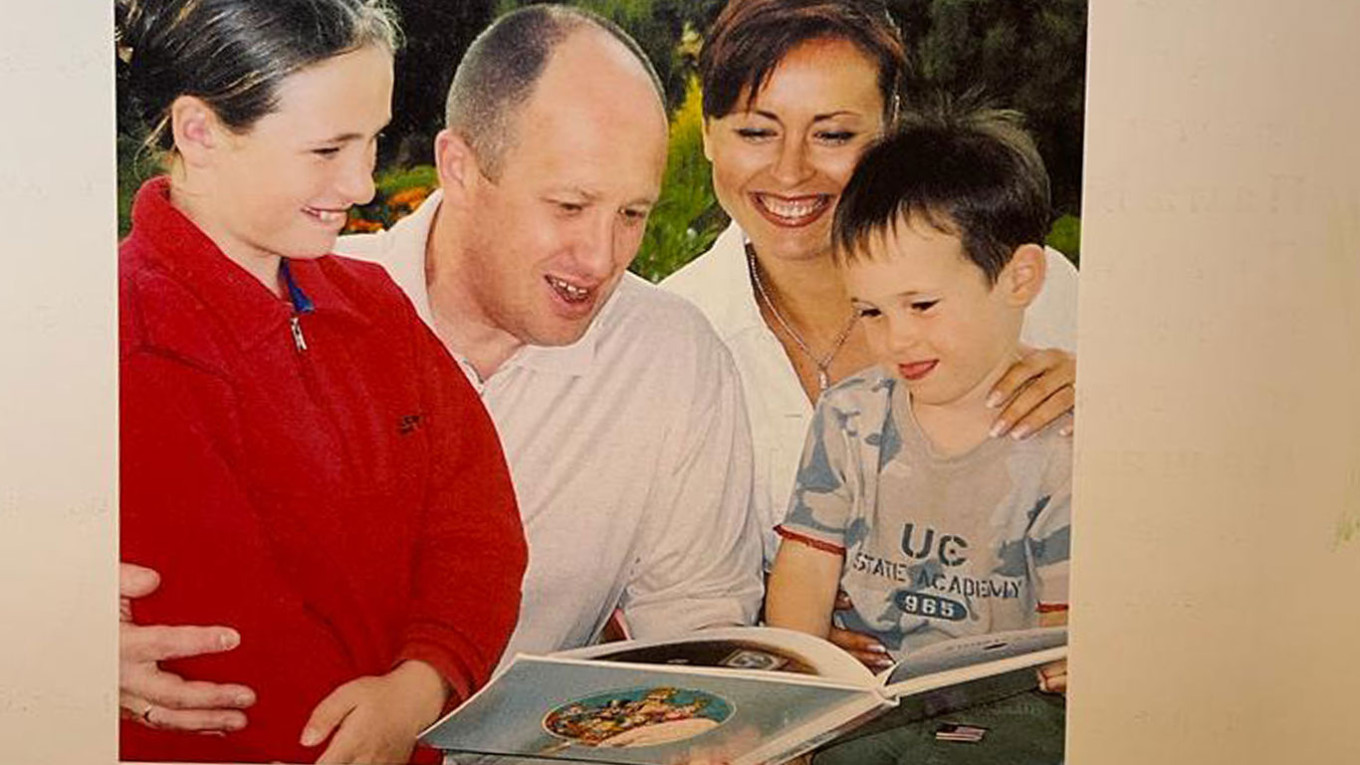

Inside its front cover, the book contains a photo of a smiling Prigozhin with both his children and their mother, Lyubov Prigozhina.

During Indraguzik’s adventures — as he tries to find his way back to the chandelier — he meets a cast of characters including another “small person” named Gagarik, who is described as an “older man with a bird and a trench coat made from rough cloth.”

Gagarik cooks soup for the boy, a possible reference to Prigozhin restaurant business.

Eventually, Indraguzik ends up in “Big City” where he befriends a human boy — aptly called Big Indraguzik — who decides to help his namesake and finds a balloon on which he can fly back to the chandelier.

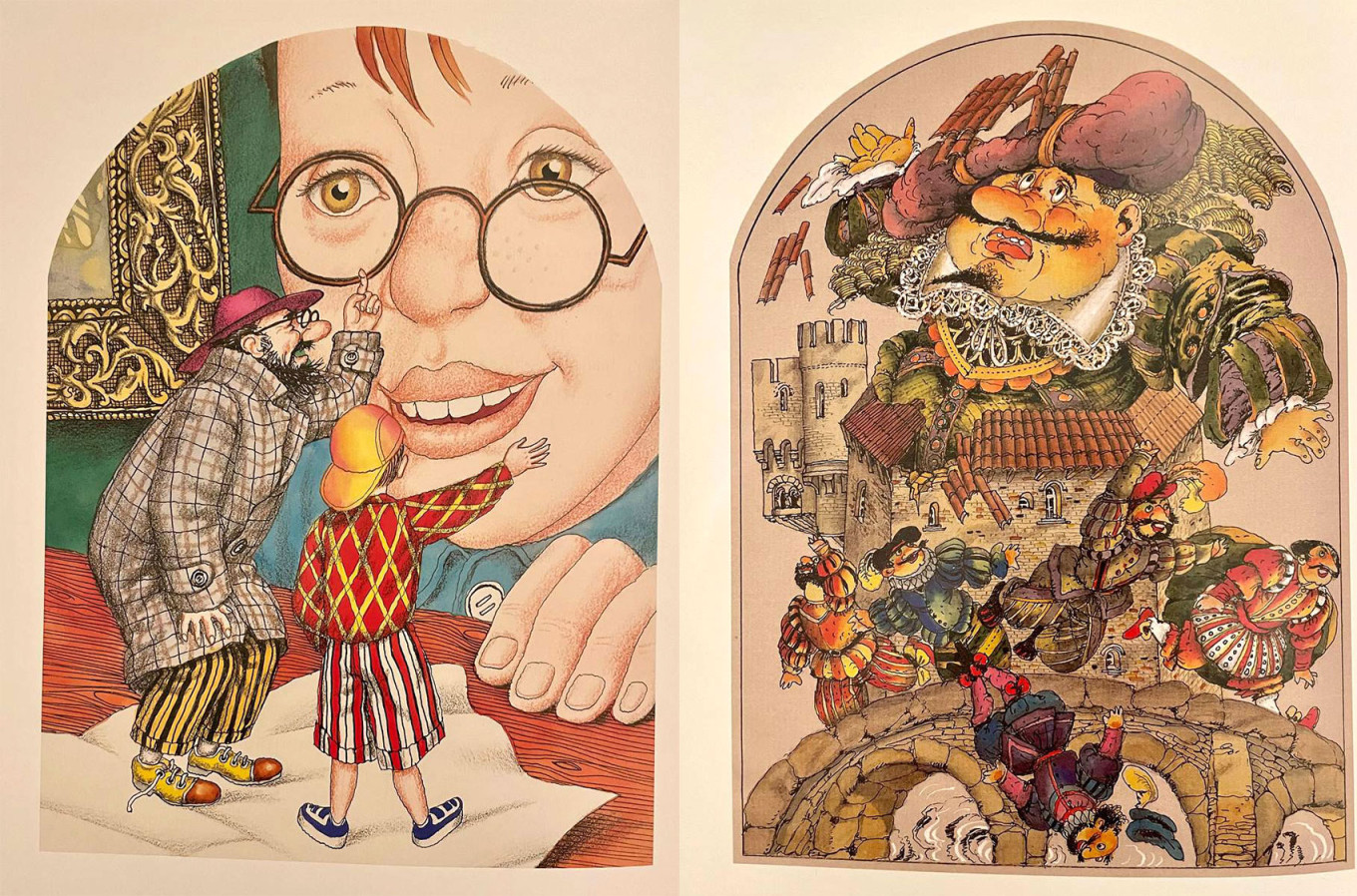

Throughout the 90-page book, there are detailed and engaging illustrations that are attributed to Prigozhin — although there is no other public evidence of the Wagner leader’s artistic skills.

Later in the story, the family’s chandelier is discovered to be magic — and capable of enlarging small people to the size of ordinary humans.

On a search to find where they come from, Indraguzik and his friends make a journey to their native land of Indroguzia, where they meet its king.

In an attempt to help the king, Indraguzik and his friends use the chandelier to make him bigger, but miscalculate — and he turns into a giant.

“How can I rule my people if they are so small? I could destroy them by mistake. Please make me the same king I was. Only a small king can rule the Indraguziks,” the king tells them as he pleads to be returned to his original size.

At the end of the book, a short poem describes the story of Indraguzik’s many adventures as “funny and strange.”

It’s believed that “Indraguzik” was never put up for sale, but was instead given to Prigozhin's friends and business associates as a gift.

Prigozhin’s children, with whom he wrote “Indraguzik,” have apparently followed in their father’s footsteps. Prigozhin has said his son Pavel, 27, fought for Wagner in both Syria and eastern Ukraine.

His daughter Polina, 30, is reportedly the owner of a luxury hotel in St. Petersburg.

When asked about the chasm between Prigozhin the children’s author and Prigozhin the warlord, Moscow-based psychologist Karina Militonyan told The Moscow Times that one man was capable of “combining all kinds of characters.”

Some observers believe that Prigozhin’s outspoken criticism of top officials means that he has political ambitions — and could reinvent himself again as a civilian leader.

Russian political expert Konstantin Kalachev, who was familiar with “Indraguzik,” said it was a “nice” story.

He described Prigozhin as someone who has evolved with the zeitgeist in Russia, shifting from convict to children’s author, friend of the president and mercenary leader.

“He is like a mirror of the times,” said Kalachev.

“He’s a diverse person, striving for self-realization within what is possible. As long as being good was in fashion, he was good. But then the time came for evil, and he became evil.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.