As the head of the banking oversight department at Russia’s domestic intelligence agency, Colonel Kyrill Cherkalin wielded immense power: With a click of his fingers, he could cause bankruptcy or give a zombie bank a new lease of life. But then it all went wrong: earlier this year he was arrested on fraud charges and 12 billion rubles ($180 million) in cash and jewelry was found in his apartment and other places linked with him and his colleagues. The Bell and investigative website The Project looked into how Cherkalin became a key figure in the money laundering business, how he ran his financial empire, and why it all fell apart.

For a meeting at Moscow’s Vogue cafe with banker Alexander Zheleznyak in summer 2014, Cherkalin arrived in a chauffeured Range Rover wearing an expensive Rolex watch. At that moment, Zheleznyak was co-owner of Life, a large financial holding. Cherkalin immediately got down to business, suggesting that a retired officer from the Federal Security Services (FSB) be made vice-president at Probiznesbank (one of Life’s main assets) with an annual salary of $120,000, a private office, personal driver and assistant.

But this was a mere detail. Zheleznyak had already received the main demand: cede a large stake in Life to a company that will share its income with senior officials from the FSB and the Prosecutor General’s Office.

These details come from a statement from Zheleznyak, acquired by The Bell and The Project, which he gave under oath this year in the United States. His testimony is set to be used in legal proceedings that Life’s former owners have launched in the U.S. and Europe.

For the co-owners of Life, childhood friends Zheleznyak and Sergei Leontiev, dealings with Cherkalin ended very badly. After the meeting, the partners agreed to take part in the protection racket involving Probiznesbank, but they did not hand over shares in all their businesses. Later, their banking license were revoked by the regulator, criminal cases were started against them, and both fled Russia. The Central Bank believes that Life was engaged in illegal financial activity, while Zheleznyak insists they went bankrupt because of pressure from the authorities.

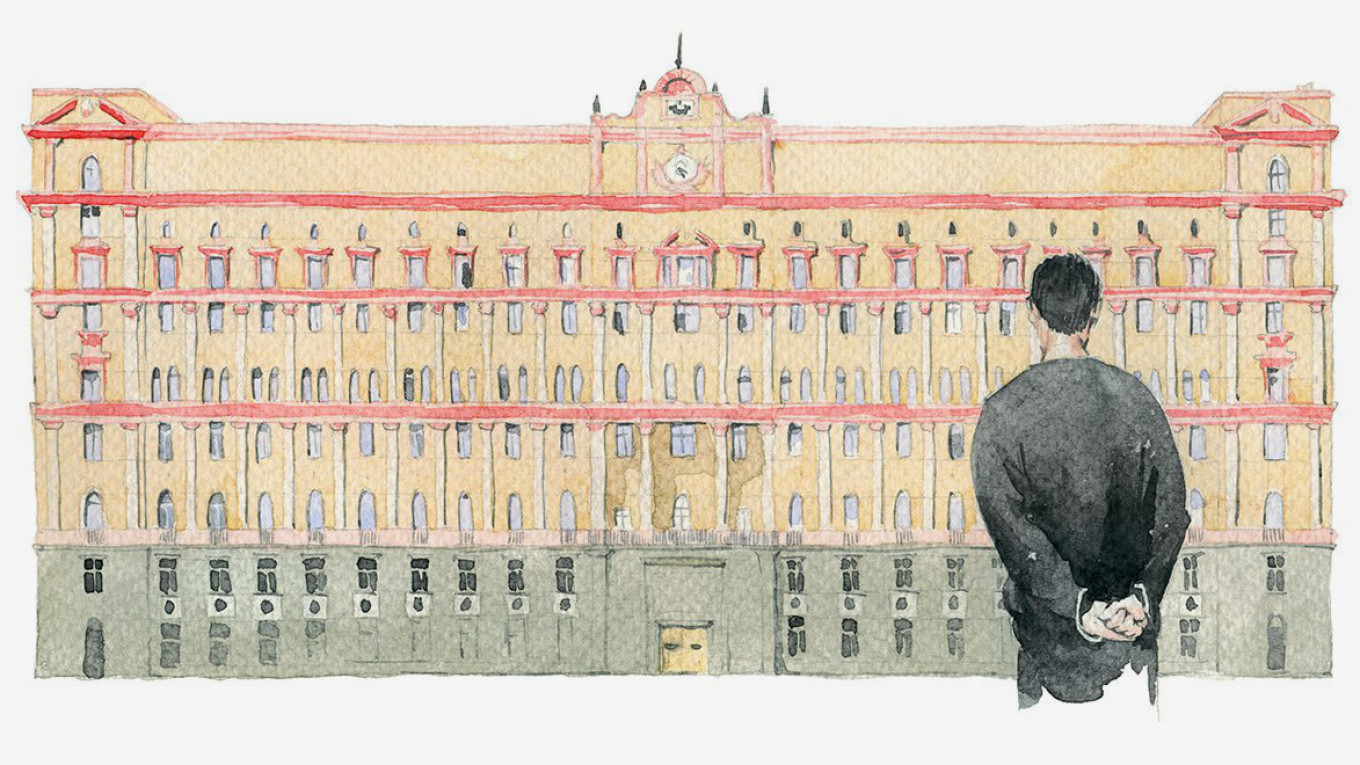

The tale of Life is just one in which Cherkalin, 38, and his FSB colleagues played starring roles. Cherkalin’s department at the FSB oversees the financial sector (banks, pension funds and insurance companies) and is one of the most powerful branches of the notorious Department K, which is responsible for economic security.

The two men arrested at the same time as Cherkalin were his former boss, Dmitry Frolov, and the more junior Andrei Vasiliev. While Cherkalin was still in his post when he was detained, Frolov and Vasiliev were dismissed several years earlier, after newspaper Novaya Gazeta published details of real estate allegedly owned by them on the shore of Lake Maggiore in Switzerland and Italy.

Protection racket

“Brilliant, very smart, well-versed in the field” is how Cherkalin was described by one major Russian banker. “But these are business guys, that’s what their [whole] generation is like.”

These sorts of commercially-minded FSB officers rose to power in the early 2000s at the same time as Russia’s money laundering business was booming, according to a source close to the FSB familiar with Cherkalin and his colleagues. “You know the principle: If you realize it’s useless to fight something, you have to lead it,” he explained.

Department K at the FSB had two main ways of interacting with banks: either they demanded a percentage of all withdrawals into cash (up to 0.2% of the transaction), or they took bribes and payoffs for specific violations, said a source close to the FSB.

To ensure the percentage was paid, whole protection rackets were established. This usually took the form of a retired FSB officer being given a position at the bank’s security team from where he could monitor cash flows. The ex-officer was also responsible for collecting information about the market. This scheme exactly matches what Zheleznyak said in his testimony about the ex-FSB officer that Cherkalin suggested employing at Probiznesbank.

The FSB did not respond to a request for comment.

At the end of May 2019, Cherkalin was visited in prison by prison monitors, who were surprised to see him wearing an expensive Givenchy tracksuit. Cherkalin’s cell was decorated with so many icons that some newspapers compared it to an Orthodox chapel.

Milking the money launderers

The system over which Cherkalin ruled was built up over several years, and was familiar to many bankers, particularly those involved in the money laundering business.

Mikhail Zavertyaev, a former со-owner and deputy chairman of Intelfinance bank, which collapsed in 2008, is one of those bankers. His relationship with Department K began in 2007 when he met Yevgeny Dvoskin, a mysterious figure described as a key player in the money laundering market with close ties to both the FSB and criminal gangs.

In an interview, Zavertyaev recalled how, in December 2007, he caught his chief accountant trying to arrange a credit line to a front company supposedly linked to Dvoskin. The following day, Dvoskin and his bodyguard, who spoke like a mafia enforcer, arrived at his offices in an ambulance. “Dvoskin came up to me, hit me in the ear, and I struck him with my elbow,” Zavertyaev said of the encounter. “He dropped to the floor and my first thought was that he had fallen on top of my suitcase with documents and that he would grab the suitcase and flee. I bent down to move the suitcase, he hit me with a pistol and I lost consciousness.”

Dvoskin has always maintained that Zavertyaev is a liar and, in court, argued that he couldn’t have assaulted Zavertyaev as he had been giving evidence in another criminal case at the moment the attack was supposed to have occurred.

Zavertyaev said the encounter did not end with his hospitalization after the fight. His wife’s car was torched shortly after and, over the next two months, about 11.7 billion rubles was extracted from Intelfinance. Still trying to get the money back, half a year later, Zavertyaev said he met Frolov, Cherkalin and Sergei Smirnov, deputy head of the FSB, at the Palazzo Ducale, a plush restaurant in downtown Moscow.

According to Zavertyaev, his dining partners were courteous, insisting he try the salad. From the conversation, he said he realized they were well acquainted with Dvoskin and were trying to understand what evidence he had of Dvoskin’s visit. They also wanted to convince him to stop trying to retrieve Intelfinance’s lost money. Eventually, he was offered financial compensation, which he said he refused. All Zavertyaev’s subsequent efforts to use the courts to get the money back have come to nothing.

Dvoskin was under the protection of the FSB, according to two sources close to Russian security agencies. When asked about his connections to the FSB, Dvoskin hung up the phone.

Cooperation between the FSB and banks carrying out money laundering was apparently extensive. The FSB “took the money launderers under its wing and made them its informers,” one source close to the security agency told The Bell and The Project. One of these informers he named as Aleksei Kulikov, the former co-owner of a small bank, Kreditimpeksbank, who is currently serving a 9-year prison sentence for fraud.

A source close to the FSB recalled that, at first glance, Kreditimpeksbank’s offices in the mid 2000s never looked like much: a half-empty banking hall, about 20 shabby rooms for staff and a gloomy looking security guard. But, according to the source, the bank was a big player on the money laundering market and the company’s security team was headed by a former Department K officer who received up to 3% commission on all financial transactions. Kreditimpeksbank had several run-ins with the Central Bank, but, each time, the FSB was able to help resolve the problem. According to the source, Kreditimpeksbank had several large clients with access to state funds and used fake contracts to move large amounts to construction firms in Turkey and Malta.

When Kreditimpeksbank was shut down by the regulator, it was estimated it had a 229-million-ruble black hole in its balance sheet and was conducting 13.5 billion rubles ($200 million) worth of suspicious deals every year. About 2 million rubles in cash was found in Kulikov’s apartment during a police search.

Mysterious disappearance

Cherkalin’s influence was not restricted to banks in the money laundering game. He was also in contact with both the heads of the major Russian banks and the senior officials running the state’s financial regulatory bodies.

Valery Miroshnikov, the former head of Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA), which guarantees deposits in the case of bankruptcy, is currently a witness in the case against Cherkalin. Immediately after Cherkalin’s arrest, Miroshnikov left Russia (according to friends he first went to Australia, and then to Germany for healthcare reasons) — and has never returned. Two and a half months later, the DIA announced his resignation without giving a reason.

There are few details about the link between Cherkalin and Miroshnikov, but one source called them “good friends” and news outlet RBC has reported that investigators are looking into messages the two men exchanged. Miroshnikov is also alleged to have been involved in extortion. The former owner of Mezhprombank, Sergei Pugachev, was allegedly approached in 2011 by two men, one of whom worked for Miroshnikov, with a simple message: hand over $350 million or risk your own life and that of your family.

Pugachev’s lawyers have been telling this story in court since 2014 when the DIA began a legal drive to track down his assets and hold him liable for Mezhprombank’s debts. The Bell and The Project were unable to contact Miroshnikov, but he has previously denied authorizing the intimidation of Pugachev.

The DIA’s task is to manage the assets of banks that have collapsed or been shut down by the regulator, paying out deposits and seeking to recover assets. Over the 15 years of its existence, it has received more than 1 trillion rubles ($30 billion) from the Central Bank.

FSB infighting?

Many have pointed out the big gap between the severity of the allegations levelled at Cherkalin, and the charges on which they were formally arrested. Officially, Cherkalin and his colleagues are accused of stealing assets worth 499 million rubles ($7.7 million) from Moscow developer Sergei Glyadelkin, and Cherkalin is accused of taking a bribe worth 50 million rubles ($770,000).

Glyadelkin, who appears successfully to have stood up to the FSB, is not widely known, but has had a long career in Moscow. Until 2005, he was employed by a state company that distributed plots in downtown Moscow to developers and builders. But he also worked with Igor Chaika, the son of Prosecutor-General Yuri Chaika, and in Fall 2013, they set-up Techno R-Region, a waste management company. The Prosecutor General’s Office did not answer questions from The Bell about its relationship with Glyadelkin.

One former senior security officer said that the 12 billion rubles found during the detention of Cherkalin and his colleagues indicated “someone inside the intelligence services knew such a payment was in the offing.” The raid was deliberately planned to catch them with the cash, he said. “To keep such a sum of money for a long time is pointless; it looks like they were stockpiling it before selling it or sending it abroad.”

When asked why Cherkalin was arrested now, a businessman with good connections in the security services replied simply: “infighting” A major Russian banker, who knew both Cherkalin and Frolov, agrees. FSB director Alexander Bortnikov is 68 and the prospect of his retirement is fueling bitter battles among possible successors, according to another source. With the FSB the most powerful institution in modern Russia, victory means nothing short of gaining total control over the country.

Reporting by Anastasia Stognei and Roman Badanin. Editing by Ira Malkova and Howard Amos. This is an abridged translation of a Russian article published July 31.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.