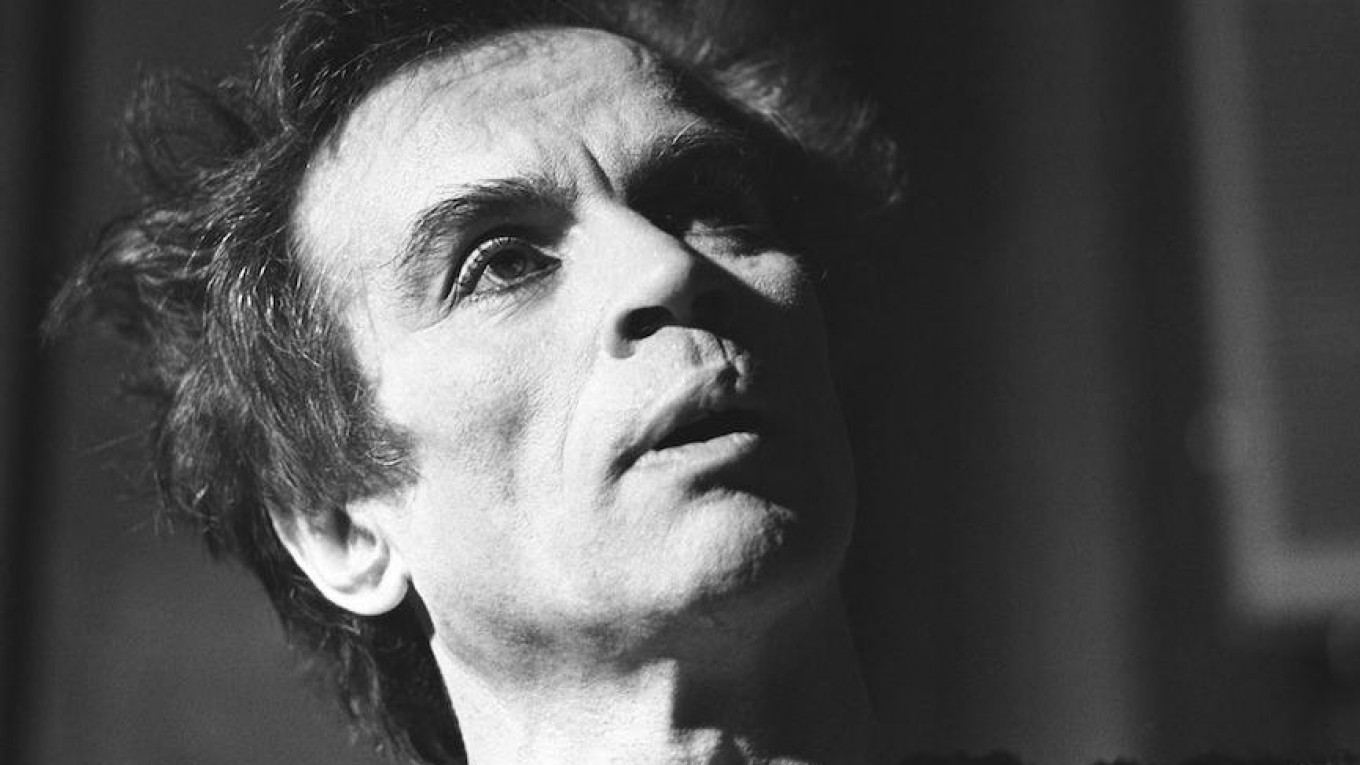

Everyone was talking about the Bolshoi Theater’s ballet “Nureyev“ long before its planned premiere.

There were various reasons for this: certainly the personality of the ballet's main character, the world-renowned dancer Rudolf Nureyev himself, but also the creators of the ballet who had such success with their production of Mikhail Lermontov’s “A Hero of Our Time“ at the Bolshoi in 2015.

But all that talk was nothing compared with this week's news that the ballet's premiere had to be postponed because it was not ready.

No one wanted to believe this, and speculation rose like yeast, with each version more outlandish than the last.

Some versions make some sense. For example, the ballet's director Kirill Serebrennikov is a witness in an embezzlement case against a group connected to his Gogol Center.

His version of “Nureyev“ is based on the dancer's personal life — including his defection from the U.S.S.R in 1961 and his romantic relationship with the Danish dancer Erik Bruhn.

The ballet apparently couldn’t be made without a duet of the two dancers and the issue of homosexuality in its now standard depiction (half-naked men in high heels and skirts). The real-life libertine lifestyle of the main star was part of the script and made the production provocative.

Why the Bolshoi Theater wanted to stage this ballet is a separate issue. Nureyev never set foot on its stage. It would have made more sense at the Mariinsky Theater, where Nureyev started his career; or at the Paris Opera, where he danced and was artistic director; or in London, where he danced with the Royal Ballet for 15 years.

The ostensible reason given — that Nureyev was a genius transcending time and space — is not persuasive. How could Nureyev be called a “God of dance” when his contemporaries were the brilliant dancers Vakhtang Chabukiani, Vladimir Vasiliev and Mikhail Lavrovsky?

No, Nureyev is interesting precisely because of his fate: a boy from the boondocks who became a ballet idol and an international sensation.

Since the announcement, it is amazing what versions the overzealous public has invented.

Since the announcement, it is amazing what versions the overzealous public has invented. The main version is a conspiracy of the management of the Bolshoi and Culture Ministry against the ballet’s creators. In this version, there was a call from above banning the performance as immoral.

All of these conspiracy theories cast doubt on the right of the theater to pass judgments and make decisions about its own repertoire. They also deny the Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky the right to speak (if he did).

But the theater's director, Vladimir Urin, has the right — in fact, the obligation — to make such decisions if need be. And the culture minister cannot be barred from involvement in one of the most important cultural institutions under his direction.

Not even a special press briefing at the theater could dispel the tension. Urin gave an almost hour-by-hour account of how he decided to postpone the premiere because it was not yet ready. And knowing the current style of work at the theater, I’d be amazed if it’s ready by the new date.

The thing is that everyone is incredibly busy with other projects. They carve out time to rehearse at the Bolshoi in-between their other obligations. They send stand-ins, don’t show up for their rehearsals, and meet whenever they can — not every day.

The director’s honest statement ruined everyone’s conspiracy theories, despite attempts to question him, catch him in discrepancies, or challenge him with preposterous notions in order to buttress their amateur arguments.

Liberal journalists — not all of them, of course — are prepared to believe anything but the truth. And the truth is that the choreographer Yury Possokhov did not meet his deadline, whole sections for the corps de ballet were still missing, and many dancers had yet to rehearse on the Bolshoi's stage.

A ballet cannot be shown in this state. Even the creators agreed with that — especially after their recent success.

But that’s not very interesting. It is far more interesting to create a fictional reality, mixing lies and truth, and topping it all off with a burning social issue.

How politicized our society is if it can be divided so easily by nothing more than a routine production problem.

Now everyone is waiting for May 2018 when the final production is ready to debut. But the problem remains: People are still incredibly busy with other projects. They’re already saying that they’ll fly in for a couple of days here and there, work through their stand-ins, and so on.

That’s the style today — do everything but what you have to do.

Alexander Kolesnikov is a Russian theater critic.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.