KHABAROVSK — As they have for nearly three weeks, the first protesters started to gather at Lenin Square in the city of Khabarovsk in Russia’s Far East at 7 pm on a recent weekday evening.

They were soon joined by independent Russian journalists and a small army of YouTube bloggers, a growing profession in Russia as news consumers increasingly switch from television channels controlled by the Kremlin to the largely uncensored internet. Journalists from state media were notable by their absence.

As the square in front of the governor’s administration building filled up, one of the bloggers, Sergei Aynbinder of the RusNews YouTube channel, started his live broadcast by firing questions at demonstrators in the style of a television reporter. But for a moment, he switched out of character.

“You know the saying that the sun rises in the east?” he said to one protester. “Well, watching all this, I’ve been thinking that maybe civil society will rise in the east, too.”

This has been the main thought on people’s minds in the city — which is closer to Beijing than Moscow — for 17 straight days of unprecedented and swelling protest. The flagship Saturday rally turning out people by the tens of thousands has grown each week, while smaller weekday demonstrations have kept up the momentum. The question now is how long the movement can be sustained.

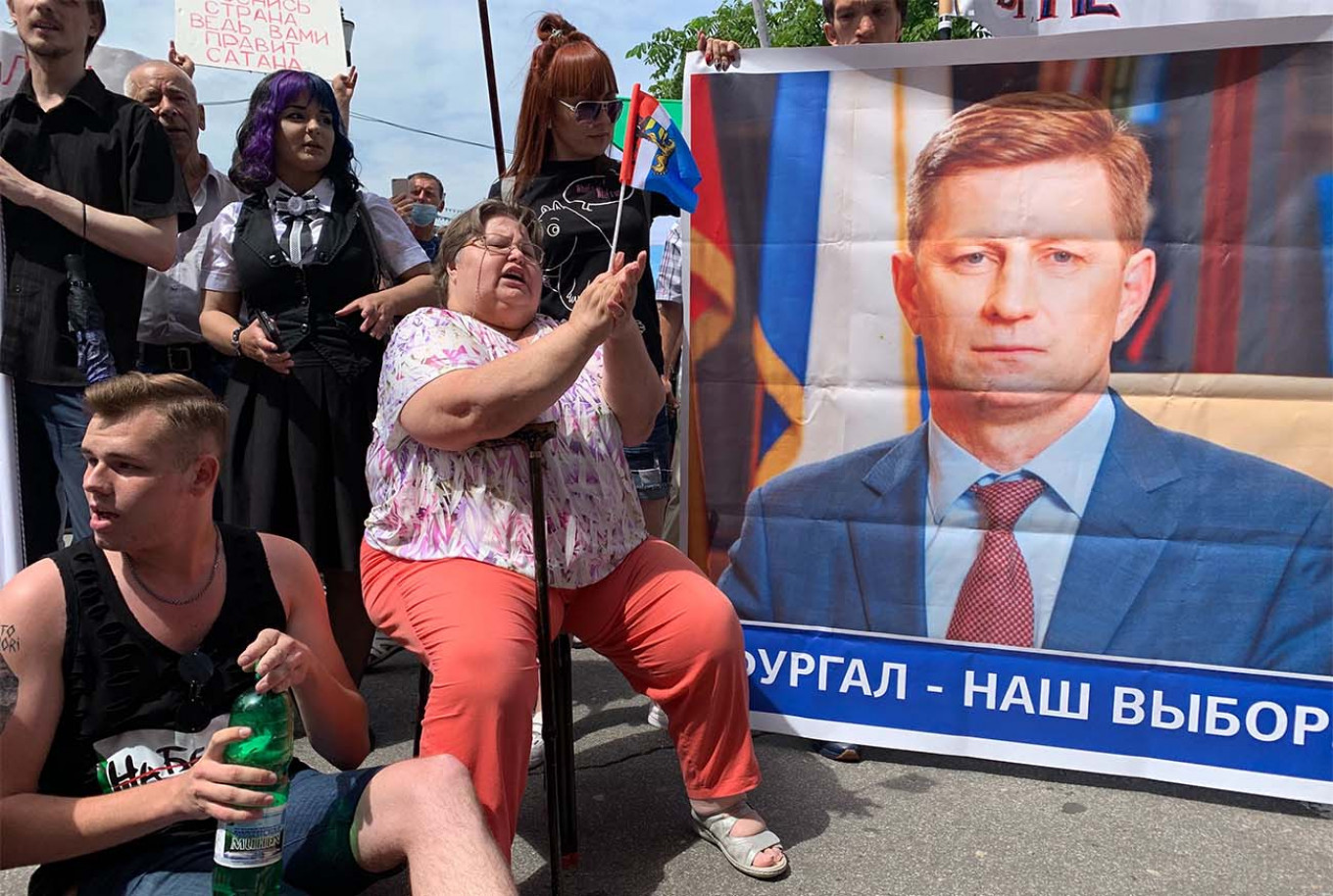

After kicking off on July 10, the day after the Khabarovsk region’s overwhelmingly popular governor Sergei Furgal, 50, was pulled out of his SUV and whisked to the Russian capital on historical murder charges, the protests in his support have evolved into a deeper expression of anti-Kremlin discontent.

After President Vladimir Putin last Monday removed Furgal, who was elected in 2018, from his post, and named Mikhail Degtyaryov, 39, as acting governor until elections can be held next September, the anger intensified.

Although Degtyaryov represents the same party as Furgal — the far-right Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) — he has never lived in Khabarovsk.

“It was a punch below the belt,” Pyotr Emelyanov, a Khabarovsk regional deputy who after the decision said he would leave LDPR and remain in office as an independent, told The Moscow Times.

Emelyanov explained that he had only joined the party because of Furgal, and that the voters who helped put him into office the next year had likewise only supported the party because of the so-called “people’s governor.”

He said his voters, who see the charges against Furgal as politically motivated payback for his election victory against the ruling United Russia party, had contacted him in droves asking him to renounce LDPR.

Further angering Khabarovsk residents, Emelyanov added, was Degtyaryov’s decision not to immediately come out to the square to meet them.

“Under your windows there’s practically a revolution taking place and you’re sitting up there having meetings,” the regional deputy said.

On Sunday evening, nearly a week after arriving in Khabarovsk, Degtyaryov finally visited the square at 11 pm to meet with the small number of protesters that remained. He offered to create a working group through which residents could voice their complaints instead of taking to the streets.

But the night ended on a sour note when one of the loudest voices of the past weeks, Valentin Kvashnikov, who had already been charged with participating in an unsanctioned protest last week, was detained. According to Russian law, demonstrations have to be agreed in advance with the authorities. They have not approved any of the Khabarovsk rallies.

While the Kremlin has so far allowed the protests to proceed peacefully, many believe the authorities could use the coronavirus pandemic as a pretext to put the city under quarantine. Regional authorities already on Saturday announced a sharp rise in infections and the arrival of medical equipment and personnel from Moscow to support the region.

There are also signs that the authorities will continue to target individual protesters. On Monday, Artyom Mozgov, a 20-year-old activist, was charged 10,000 rubles ($140) for participating in unsanctioned protests.

Although Mozgov told The Moscow Times it wouldn’t stop him from joining the next protest, he has already been charged once, opening him up to a charge of repeat violations. In the crackdown on protests over fair elections in Moscow last summer, a judge handed a sentence of four years in a penal colony to one protester for that exact crime.

But while the authorities may try this tactic to cool things down, Alexei Vorsin, who heads Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny’s local office in Khabarovsk, believes the strategy won’t work as the movement has no clear leaders to go after.

And if the authorities try to detain people en masse while tens of thousands take to the streets every Saturday, they will only “pour fuel on the fire,” he said.

Yet Vorsin, like other activists who spoke with The Moscow Times, also worries that the movement could peter out by the end of summer if its demands don’t become more concrete and coalesce under a visible leader.

Indeed, Ildus Yarulin, a politics professor at Pacific National University in Khabarovsk, said it appears to have taken on a “carnival-like atmosphere,” which he sees as an expulsion of pent-up frustration and post-quarantine euphoria taking the form of anger against all authority.

“It’s certainly a sign of an unhealthiness in the society,” he said.

For their part, protesters say they believe their concerns are being ignored by the Kremlin and deliberately not broadcast to the rest of the nation. On Saturday, when the highest estimates put the size of the crowd at 100,000, they often broke into chants of “Russia, wake up.” Some explained the slogan by saying they believe their movement needs recognition beyond Khabarovsk if it is to last.

Other protesters told The Moscow Times they are looking to other recent protest movements in the post-Soviet space for inspiration to keep the momentum going. Some pointed to Armenia’s successful 2018 revolution, noting that what was key there was that the rallies maintained size. They also talked about the mass protests that have kicked off in Belarus after officials barred President Alexander Lukashenko's main rivals from running for election in August.

“We’re all just tired of feeling like cattle,” said Konstantin Grechanov, a 49-year-old artist. “It’s the same in Belarus. We are fighting for the right to have a choice.”

On Saturday, Alexander Kivlyov, 57, was taking a break outside his restaurant as thousands of protesters streamed by, snaking their way back to Lenin Square. He said he would have joined the rally if he didn't have to work.

“Maybe it’ll be like Lenin said. You just need a spark for a revolution to begin.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.