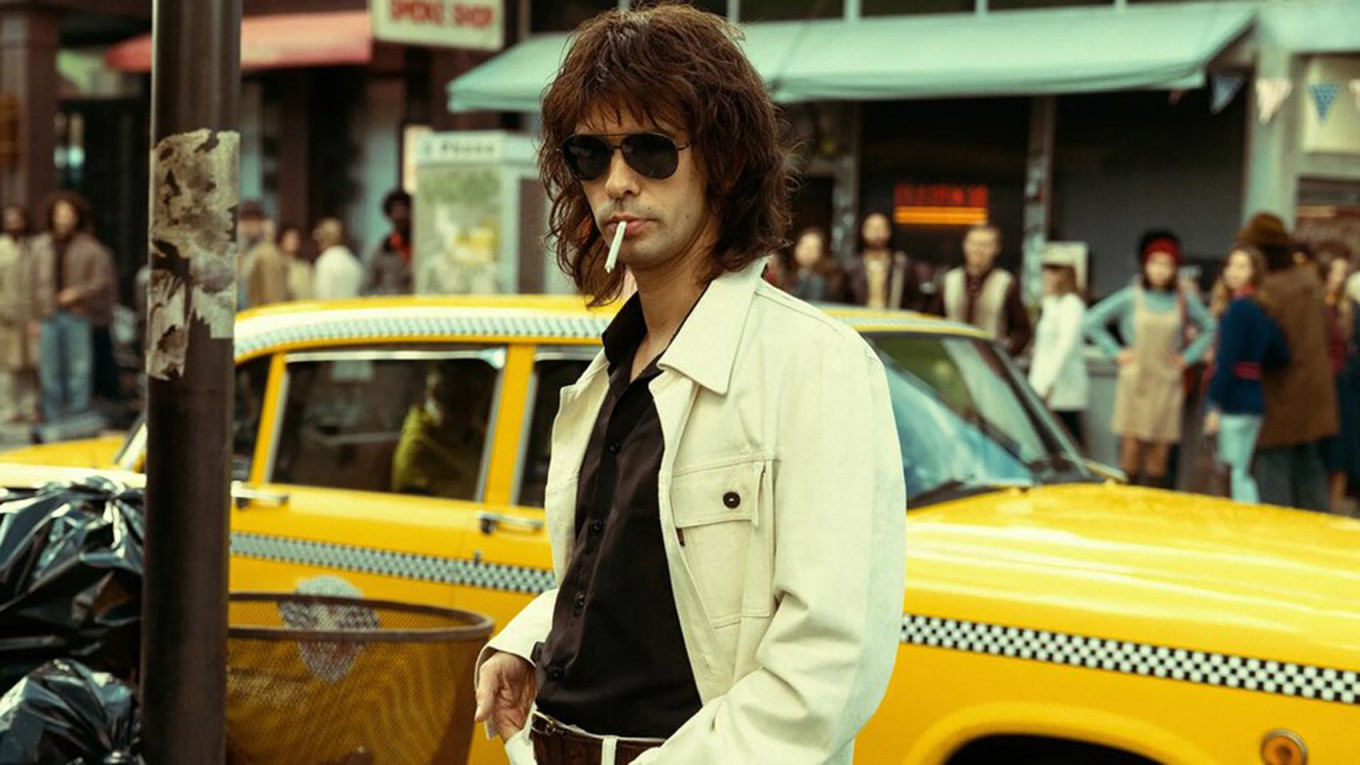

“Limonov: The Ballad,” directed by Kirill Serebrennikov, was screened at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released in the US in September.

The screenplay, written by Serebrennikov with Ben Hopkins and Paweł Pawlikowski in an adaptation of Emmanuel Carrère’s 2015 fictionalized biography, tells the story of the poet, writer and Soviet dissident who became a supporter of the revival of the USSR. MT spoke with the director in an exclusive interview.

Moscow Times: Who was Eduard Limonov, a hero or a villain?

Kirill Serebrennikov: For me, he was a Russian Joker. A person with several faces who multiple times would die and be reborn in a new body, environment, and nation, starting a new life each time.

I never met him. He was very influential in the 1990s in Russia, the time of my youth. He was attractive — he looked and behaved like a rock star. A lot of young people read Limonka, the newspaper he published in the anti-West tradition. He called himself a Self-[Declared]-Russian-Fascist.

I wanted to show how a creative personality becomes a character of war. This can give you an idea about the roots of violence and Russian fascism. And if you ask how contemporary he is – I would say he is quite contemporary. All of Russian aggression has an example in contemporary history, reflected in what Russia is doing now with its invasion [of Ukraine]. It shows how quickly such things can happen. Limonov is like a metaphor for Russia. He has a complicated personality, probably a bit romantic, and way too anarchic. He is very contradictory – not always clear in his intention. For me, this is an important message about what Russia is.

Limonov liked to be against everyone, as Russia is now. I often get the impression that today we live in Limonov’s world, and that the Russian authorities revered his latest works and acted as Limonov suggested. We started a war, set out to restore the Soviet Union, and what once seemed crazy to us has become our very toxic reality. Here is an example of how a movie character can intertwine with real life.

This film leaves romanticism aside but forces us to ask not-so-pleasant questions of ourselves. Limonov is first and foremost a poet. His poems are still beautiful, especially the early ones, despite what he later said and did. These poems express the real nature of this country. But then some kind of metamorphosis happens to him, and this is what our film is about. How can you turn from a poet into a man of war? And if he is a romantic, it turns out that romanticism is characterized by military aggression. After all, Byron was not alien to the same psychology and perception of the world.

MT: In your film how did you recreate New York of the 1970s?

KS: It was one of the most difficult parts of this film to recreate New York of 1974. I know everything about Moscow of 1989 and I have an idea about Moscow of 1993, but New York of the 1970s was a long journey. First, I spent a month in the Associated Press footage storage, watching videos they used in their broadcasts, including street views, faces, and restaurants. Then I found huge archives of street photographers. During the makeup sessions, I would show the makeup artist a random photo from a street in New York of that time and say I needed the same character, with the same face and dress. Everything you see in my films has a connection with the reality of that time; it wasn’t pure imagination.

We built sets in Moscow before Russia invaded Ukraine. When the war started and people began leaving the country, the old set, which was quite expensive, was sadly destroyed. Six to seven months after we left Russia, producers found another affordable solution in Latvia, near Riga. It was a bit nostalgic because some parts of the area reminded us of the past. We also used technologies to merge our shooting material with original footage.

MT: There is a sex scene taken from Limonov’s biography “It’s me, Eddie.”

KS: Yes, when Limonov has sex with a black homeless man. The funny thing is that when I meet journalists from Russia, they always ask questions about that scene. It is the main question for them, while others ask me why I skipped the scene where Limonov took part in the siege of Sarajevo.

I understand. It was the first homosexual scene in Russia ever. I remember when we read this scene back in the 1990s, we could not believe it. Cyrillic letters had probably never described any acts like this before. For me, this act was just part of the trickster’s behavior; it was an act of his immense love for Elena, who had left him by this point. He was not doing it to change his identity. He was straight his whole life. This scene is one in which he is dying to be reborn again.

MT: Limonov once said that a writer must be kicked out of the country if he wants to become a professional. Can you relate to this, since you also left Russia, becoming an immigrant?

KS: I do not see myself as an immigrant. Even the term is unpleasant for me to say. We do not live in Soviet times anymore. For Limonov, it was a one-way ticket; if you left the country back then, it was forever. You wouldn’t be able to see your parents again or have any communication with them or friends. You had no information about what was happening in your country. You just cut all ties.

Today is different. I am well-informed about the situation in the country. I have my father there, and we connect every day on Zoom. I left Russia because it became impossible to live there, to express my opinion, due to the most recent and ridiculous laws, and the situation became very toxic. But in my case, it is not immigration; it is something different. Isn’t it normal for people nowadays to leave a place if they are unhappy and look for something new?

MT: How has leaving Russia affected your life and work?

KS: I left a country where I could not work and live for a country where I can do both. Now I have a lot of projects; everything is quite exciting. I am trying out new things and growing. The most important thing is that my close friends and most of my colleagues are also here with me. None of us planned to be thrown out of the country. The country decided we were not suitable for it, because we were against the decisions of the authorities. It is the country itself that abandoned us, and it is abandoning many others, such as the director and my former student Zhenya Berkovich and Sveta Petriychuk. They did nothing wrong. They staged a play that won a national theater award!

MT: In the epilogue to the film you mention that Limonov supported the annexation of Crimea by Russia. Can you comment on that?

KS: Indeed, he supported the annexation of Crimea by Russia and considered Donbas a part of Russia. He died in 2020, before the full-scale invasion. Limonov wanted to go his own way and wrote a lot of notes with slogans like “Let’s make Russia great again” and “Let’s rebuild the Soviet Union and make it a great Empire.” Maybe it was a sort of trauma after his life in the US and encounters with the capitalistic system. He was born in Kharkov, which is Kharkiv today. Back then, the city was Soviet to the core… it was full of culture, with many poets, avant-garde artists, stage performers, and a talented environment – a melting pot of several traditions and ethnicities. Those people did not see themselves as Ukrainians or Russians; they called themselves Soviets.

I wish the film could be released in Russia, as it is part of Russian history. But I know that my wish is a fantasy at the moment. All I can do is to stay optimistic.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.