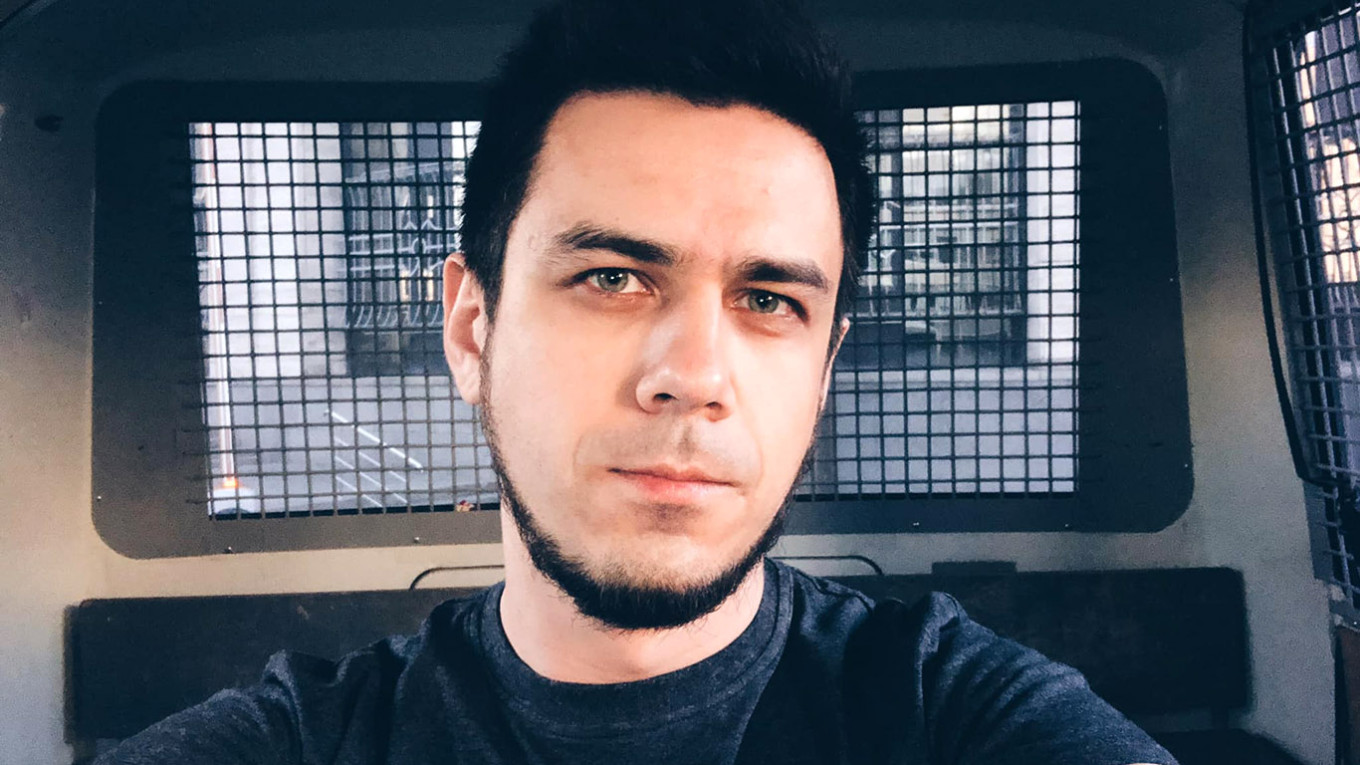

Artist Artiom Loskutov, like many Russians, had to leave the country after the invasion of Ukraine.

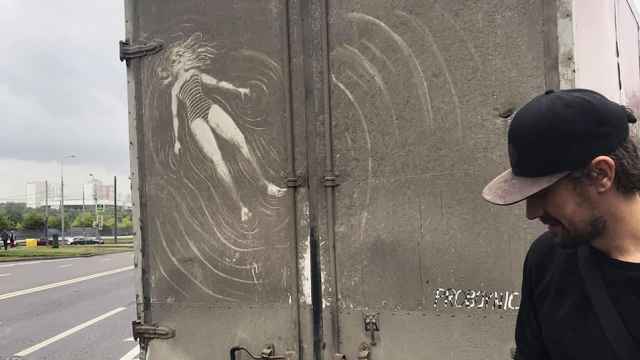

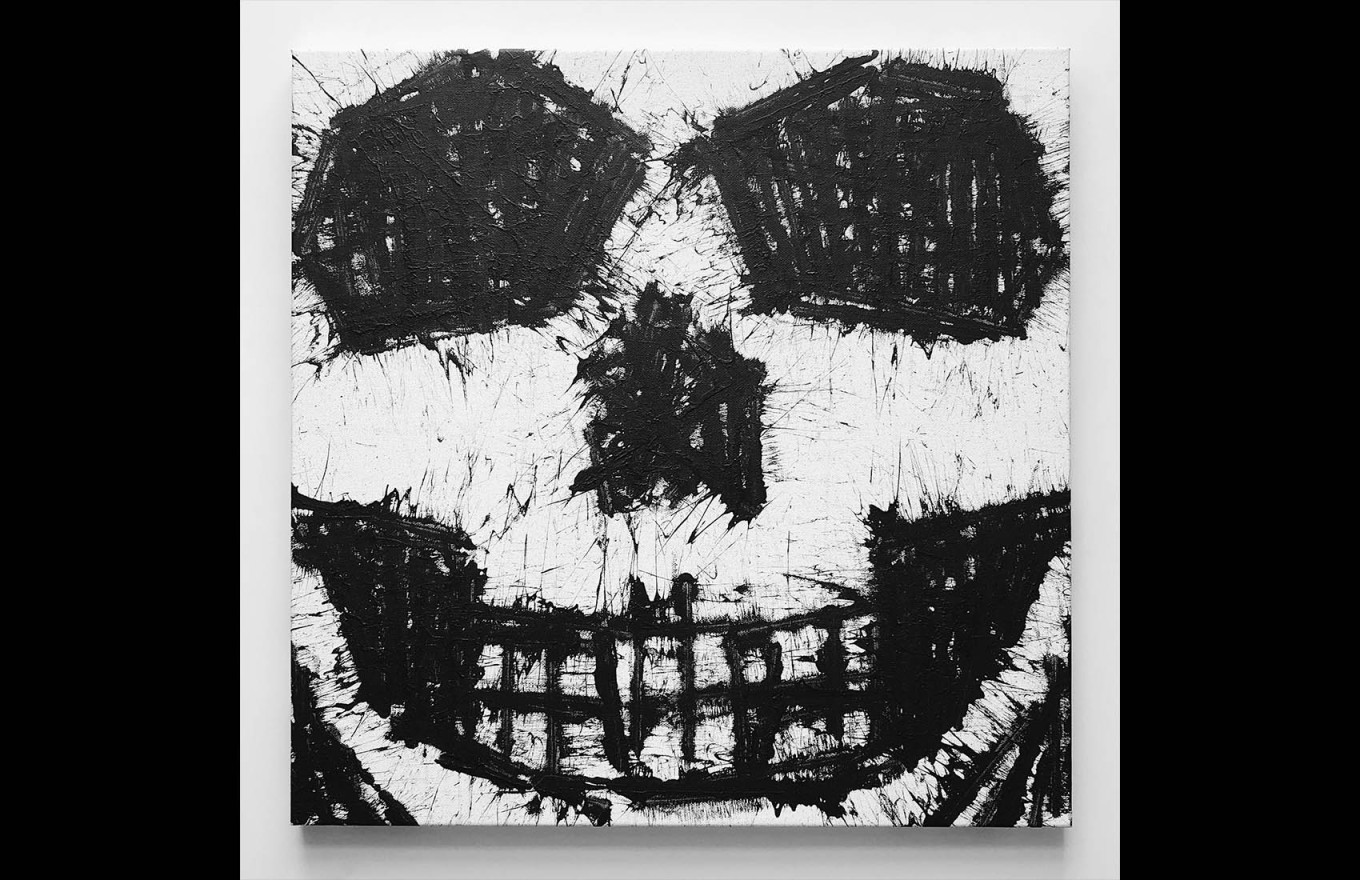

Born in 1986 in Novosibirsk, Loskutov is one of the creators of the annual "Monstration" parade, known for its absurdist slogans like "Enough tolerating this, let’s tolerate something else!" and "Our hearts demand dumplings!", as well as dubinopisy — paintings depicting symbols of state violence created using a police baton instead of a brush.

Loskutov spoke to The Moscow Times about the challenges of addressing war in one’s art, why it’s important to comment on conflicts in other countries as a Russian, and what it means to be an artist "against the Kremlin."

MT: How do you view yourself now: as a Russian artist, anti-war, against the Kremlin, or just an artist interested in various themes, including this one?

AL: I think it's a great responsibility to call oneself an "artist against the Kremlin." To fight the Kremlin means you have resources for this fight — some power, some effectiveness, that you are on the same level. And if you don’t have this, can you be called an "artist against the Kremlin"? I don't know. I've never liked the Kremlin, not today, not before the war, not 10 years ago. But now, I think I'm just an artist from Russia; I can call myself that now.

It’s interesting that you perceive the phrase "artist against the Kremlin" not as an artistic limitation, but as a responsibility.

When you call yourself an artist against the Kremlin, let’s look at your work — what’s the result of this struggle? The Kremlin uses the first, second, third, fourth and fifth methods, launches missiles, and so on. And you? I guess an artist indeed should take on more than they can handle. We love artists and are interested in them because they take on impossible commitments, acting not only based on the laws of physics but also on their imagination, and trying to break free from existing frameworks.

But we are in a situation where it’s more like the Kremlin against the artists, not the other way around. The Kremlin is a conditional regime; it's the security forces or state agencies. They choose certain artists, musicians and rappers to repress and call them enemies.

How has your life changed since Russia invaded Ukraine? What has changed in your views, art and life?

This is a big question that’s easier to joke about. But to be serious, I think there has been a significant devaluation of everything that happened before the war, everything we did. I feel this way, and my colleagues sometimes feel it too. Everything we did turned out to be useless, meaningless, unable to prevent the terrible events happening now. There were terrible events before, like political killings and repressions, but their scale has increased significantly.

Honestly, it all seemed like a game that we were playing. What was happening in our country starting in 2013-2014 seemed like an immersive show. The country seemed to be playing a show about totalitarianism inspired by the novel "1984" or something like that. It seemed like in this attraction, the people who did pro-government things were just playing their roles and didn’t take it seriously. All those TV shows broadcasted by the authorities about the "holy Rus'" and all this crap. It was impossible to take it seriously.

Maybe during Soviet times, some people believed in the Communist Party. But then our politicians, not knowing how to hold on to power, created some nonsense in place of ideology, having been free Russians for 10-15 years before that. And no one believed in this nonsense except for completely insane viewers. In 2022, it turned out it wasn't a joke; it was all quite real.

And you left Russia...

I left for a vacation over New Year’s, the war started, and I just didn’t return. Since then, I’ve been living abroad, in a foreign country.

I would even say that I’m in some border space between worlds, in limbo. In Latvia, where I am now, it feels like you’re not in Russia, but also not in someplace opposite, not like in the States or Germany. It feels like you’re somewhere in between.

Here, I’ve seen many processes I hadn’t known about, hadn’t thought about, hadn’t considered before. For example, I hadn’t thought about my Russian language, about how people might perceive it due to historical events. It turns out you bear responsibility for your passport, your origin, for what you ran away from. And all this puts pressure on you as an artist, creating new challenges.

But at the same time, my audience is mostly in Russia; I need to talk to them about something. They would hardly be interested in the life of an artist in Riga.

Is your audience not in emigration?

It’s still a smaller part, I think a third or a quarter. The rest are in Russia. Honestly, I try to know less and less about what’s going on there. It’s impossible to know nothing at all, but finding the strength to read the news every day is becoming harder. You have to distance yourself just to stay sane.

Is that why you haven’t done any works on the subject of war?

I just don’t see what can be said on this topic through art. What could be a stronger statement than what’s already in the news? And it seems I haven’t seen many works on this theme from colleagues either. Maybe time needs to pass for such art to appear.

But your recent work, "Dubinodavid," on the Israel-Palestine conflict, sparked a lot of controversy. Why did it appear now?

I made it in response to what I saw in my social media feed. I read these posts and saw people writing the exact opposite of what they had written recently about the Russia-Ukraine war — calling for aggression, writing "Lord, burn!" Some wrote that the same should be done to Russia — I don’t know if it’s right to speak this way about your own people, but about others, I think it’s definitely not okay. Or they wrote that Palestinians chose Hamas — but we, Russians, spent two years proving to everyone that we didn’t choose Putin, so why do these same people say Palestinians are to blame?

But some saw this work as anti-Semitic and supportive of Hamas.

Frankly, I think people who saw support for Hamas in this image should reflect on their state of mind and consult a specialist because there was no support for Hamas in this work. I think you’d have to try very hard to see it there.

The fact that many people are ready to accuse everyone they disagree with of supporting Hamas is very similar to what the authorities in Russia are doing. They basically call everyone who says Putin isn’t doing what he should be doing traitors to the nation.

There’s fierce polarization, perhaps even more intense than in the Ukraine-Russia conflict. No one is ready to listen to someone who doesn’t fully share one position or another.

In principle, we, people who believe Russia attacked Ukraine and committed war crimes, that the war is unjust and must be immediately stopped and all responsible must be punished, are unlikely to listen to those who think otherwise; we already consider them maniacs and fools. It probably works the same way in the opposite direction. Sometimes, through some conflict situations around a painting, we might even help exchange experiences.

I understand that the complaint might also be that the six-pointed star is not only a symbol of the state of Israel but also of all Jews. Many have faced anti-Semitism, and now a person with these experiences sees my painting and thinks I painted some anti-Semitic image. But it’s a question of what’s more important to us. We can paint only flowers... Or provoke discussion and take some risks.

Aren’t you afraid that someone might perceive your work completely differently from what you intended?

That’s a normal process. I think it’s even... cool when you can perceive a work differently than a poster.

But I would be unhappy if someone suffered because of my paintings or if my art started being used by the state for its purposes. I hope it’s like how posters of Pushkin on [bombed] Mariupol Theater represent all the sh** the government is doing now.

On the one hand, I’d already be dead and wouldn’t care, but on the other, I’d still want to believe that everything I do is done in such a way that the authorities couldn’t use it. For example, the Immortal Regiment was a grassroots initiative that the authorities then hijacked and started using for some satanic purposes. But the "Monstration" cannot be used like that; it’s aesthetically different. It’s about destroying ideology and mocking any kind of calls.

But art still changes its meaning at different times under different circumstances. For example, here in Riga, I have stickers left with the word zapreshcheno (“banned”). When I made this painting, after 2014, it was clear what it was about — at the time, the import of products into Russia was banned and they crushed imported peaches with tractors. And here in Riga, I’ll stick this sticker somewhere, and a couple of days later I see it’s been scraped off with a key. And then I realize that here, zapreshcheno means the opposite — Russian media that are blocked and whose websites don’t load are seen as propaganda. And I understand that here, zapreshcheno seems like some pro-Russian thing.

Or my American friend had a sticker that said "Big Brother is watching you and he’s bored." It’s about something else entirely, but it’s also scraped off here, because here, "Big Brother" is Russia. There’s a context that creates a different perspective, and it’s impossible to account for all this.

Are you currently able to make a living from art, or do you have to supplement your income with something else?

Yes, selling paintings brings in money, and this was an important point for me — in Novosibirsk, I didn’t even think it possible to leave my office job and focus solely on art. Paintings are not just bought by oligarchs — for example, I sometimes participate in colleagues’ auctions if I have the money and like the painting at that moment. I recently bought a painting by Siberian artist Sanya Zakirov.

Artiom Loskutov’s artwork will be exhibited at “Artists Against the Kremlin,” a showcase of anti-war, anti-authoritarianism art presented by The Moscow Times, All Rights Reversed gallery and De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 3 to Sept. 3.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.