Читаете русскую версию здесь.

LINZ, Austria — For Nadya Tolokonnikova, rage has always been an antidote to her despair at the Kremlin’s repressions.

“When something terrible happens, I’m free to choose — either I lay low in tears, or I rage. And through my rage, the better world starts to manifest,” the founder of the Pussy Riot feminist protest art collective says. “Like an alchemist, I transform rage into beauty, rage into art, rage into political action.”

In “Rage,” her debut solo museum exhibition that opens Friday at the OK Linz contemporary art museum, Tolokonnikova, 34, channels that emotion into powerful and provocative meditations on violence, spirituality, patriarchy and resistance to authoritarianism.

Consisting of sculptures, mixed-media pieces, paintings and the Situationist-style performance art for which Pussy Riot is known, “Rage” is as much an encapsulation of Tolokonnikova’s rich career as an artist and activist as it is a reflection of her present-day fury at President Vladimir Putin and his war in Ukraine.

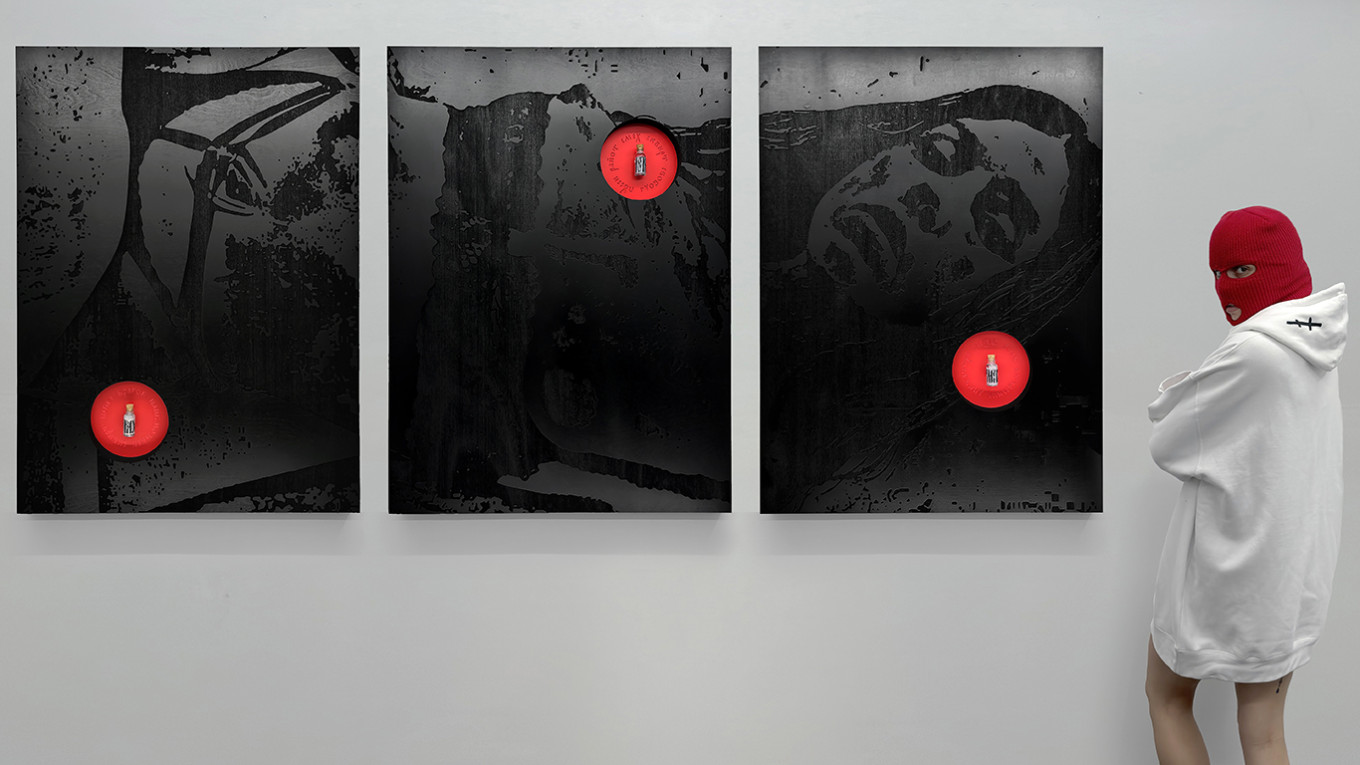

In a room called Putin’s Mausoleum, Pussy Riot’s 2022 performance “Putin’s Ashes” plays on a loop. In the video, Tolokonnikova and other balaclava-clad women from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus burn a portrait of Putin in the desert, then stab the ground in an almost shamanistic ritual. The ashes were stored in vials that are placed throughout the room.

That performance is believed to have prompted the Russian authorities to add Tolokonnikova, who lives outside Russia, to the country’s federal wanted list. She was arrested in absentia last year, putting her at risk of extradition, and certain detention upon entering Russia.

The idea for “Putin’s Ashes” came after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“I feel like Putin just destroyed bit by bit everything I ever loved,” she says. “I love Ukraine so much, but he just destroyed everything I f***ing loved.”

When the invasion started, she helped raise $7 million to support Ukrainian civilians with UkraineDAO, an NFT of the Ukrainian flag. From there, she started to consider the best way to respond to the war with her art.

“What is the role of artwork when there is war happening? It's a big question that a lot of artists must face,” she told The Moscow Times.

“I felt like ‘Putin’s Ashes’ was a good step at connecting people from different countries who are somehow influenced by Putin. And I believe in magic, in the sense that it's important to state your intentions clearly, and we did it by claiming that we want to see Putin in the form of ashes,” she says.

The exhibition’s title was taken from “Rage,” the song that Pussy Riot released when poisoned Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny was jailed upon his return to Moscow in 2021.

She says the title was inspired by women’s rage in particular — as women are discouraged from expressing this emotion.

“It was very significant to me that [Navalny’s wife] Yulia Navalnaya, in her first statement after her husband’s murder, [spoke] about rage. She said, ‘I'm not just feeling sad, I'm not just feeling grief, but I'm also in rage’,” she says.

On Thursday, Tolokonnikova and other woman-identifying activists and artists staged an enraged performance beneath the exhibition’s giant hanging blade against a background of noise music.

“The screaming woman is immediately labeled as hysterical,” she says. “But it’s not as much with men. They’re labeled assertive, confident, if they raise their voice. … So I think it’s important [for women] to scream, to take the stage.”

In a room called the Rage Chapel, a series of icons show a Pussy Riot balaclava encircled in halos of quotes from Pussy Riot’s lyrics and persecuted Russian dissidents like Navalny and Vladimir Kara-Murza — along with loaded words like “terrorist” and “extremist” which the Kremlin deploys against its critics.

Though she does not follow any organized religion, Tolokonnikova expresses spirituality in her art in what she calls “my own individual artistic religion.” She is an enthusiast of Orthodox imagery, especially Vyaz, the ancient Cyrillic decorative calligraphy, and frequently invokes the Virgin Mary as a feminist symbol.

Across from the icons hang two square paintings with the words “Pussy Riot” inscribed in Vyaz — a reference to Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, which was hung in the corner reserved for Orthodox icons in traditional Russian homes when it was unveiled in 1915.

These pieces flank a light display of a reimagined Orthodox cross that Tolokonnikova calls a queer cross or feminist cross — removing the symbol’s aesthetic beauty from the context of the Russian Orthodox Church, which backs Putin’s war and is pushing to ban abortions and deny LGBTQ+ rights.

“Even within this oppressive institution, there is something that really speaks to me,” she says.

A sense of irony, wit and mischief can be found throughout Tolokonnikova’s work. In “Putin’s Ashes,” a =^.^= emoticon is placed below the red nuclear-style button that starts the fire and “neutralizes Vladimir Putin.”

One wall is covered with prison shivs hung in plush, faux-fur frames — which Tolokonnikova created using the sewing skills she picked up in prison — negating their violent potential.

On the exhibition’s second floor stands a replica of the prison cell where Tolokonnikova was sent for two years because of Pussy Riot’s 2012 performance of “Punk Prayer” — a song calling on the Virgin Mary to remove Putin from power — in a Moscow cathedral.

Across from the cell is a wall of videos showing Pussy Riot’s past performances and music videos, illustrating the types of actions — provocative but peaceful acts that call for an end to oppression — that the Kremlin deems a threat to society.

These days, Tolokonnikova is on the path to healing from the trauma she experienced in Russian prison.

Beyond the emotional and spiritual catharsis that her artwork offers, she has taken up exercise and veganism and started seeing a therapist, understanding that self-care is a political act in itself.

“I didn't really pay much attention to my mental health or my physical wellness before I ended up in jail. I was just going and going and going non-stop: ‘I need to make a revolution’,” she says. “Going to jail … radically changed my outlook on life.”

She has found love, marrying the American NFT entrepreneur John Caldwell in January. And she has formed friendships with her personal heroes like performance artist Marina Abramovic.

“I feel like I’m in my happy phase,” she says.

The creative process and her activist work remain her main sources for feeling a sense of agency in the face of grim news from Russia and around the world.

“Create a very simple guideline for yourself. You have this problem — ‘Okay, how am I going to react to this?’ And you say, ‘In the next few months I’m going to be creating a performance art piece about it.’ And you suddenly feel better about the problem. Or you worry about the situation with political prisoners, and you give yourself a task every single day of writing to another prisoner,” she says.

“If you let yourself be overwhelmed with existential questions, like, ‘What am I doing on this planet? Do I actually have real influence?’ Just don’t, just don’t.”

Despite the dark reality all around, Tolokonnikova remains a believer in a utopian future for her country and the wider world.

In her vision of a future democratic Russia, she says she’d like to act as a radical figure who would push a moderate, centrist leader in a more progressive direction.

“Any progressive movement, any progressive party can turn into an old-fashioned institution if you lack these tricksters,” she says.

And she dreams of transforming the Kremlin into a contemporary art space and converting the Federal Security Service (FSB) headquarters into a shelter for domestic violence victims once the current regime is no longer in power.

“As activists, we’re often trapped in resistance mode, which is incredibly important. Obviously, there’s so many important issues to fight against. But we also want to create this space and time for us to dream about a better world. And I think art really can help with that,” she says.

“What is art if not an enhanced ability to dream?”

“Rage” opens June 21 at OK Linz Museum and runs through Oct. 20. More information here.

“Putin’s Ashes” will be exhibited at “Artists Against the Kremlin,” a showcase of anti-war, anti-authoritarianism art presented by The Moscow Times, All Rights Reversed gallery and De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 3 to Sept. 3.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.