Sergei Tyutryumov was executed by shooting on March 7, 1938. He was 33 years old.

Soviet authorities accused him of “counter-revolutionary” activities and “anti-Soviet agitation aimed at undermining the authority of Soviet power.”

Two years prior, Tyutryumov, a descendant of a noble family, moved to the Siberian city of Tomsk to work as a history teacher and lived there with his wife and two daughters until he was arrested and sentenced to death.

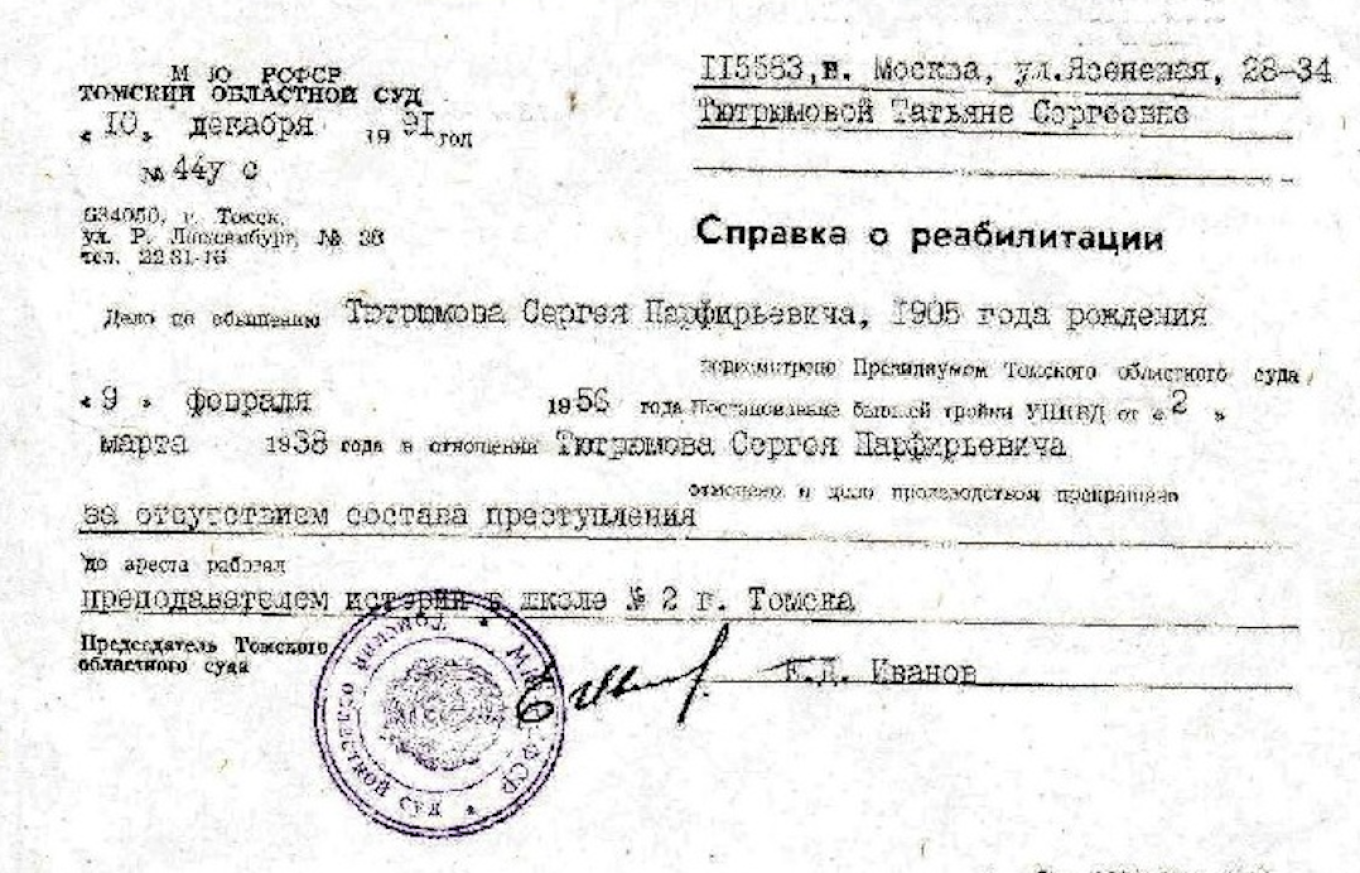

He was fully rehabilitated in the 1950s due to the absence of a crime committed. Until they found out, his family had no knowledge of Tyutryumov’s fate and believed he might still be alive.

Almost seven decades later, Tyutryumov’s relatives were able to honor his memory as Posledny adres (“Last Address”), a project that pays tribute to the victims of repression, installed a memorial plaque in his honor on the house where he lived in the 1930s.

"We are very glad... that the memory of our grandfather will be preserved," said Tyutryumov’s granddaughter Elena Shatunova at a small ceremony to unveil the plaque in Tomsk.

“This is very, very important for us,” she added.

Seeking justice

For the past decade, the Last Address project, founded in Russia by the journalist Sergey Parkhomenko, has been commemorating individuals who fell victim to the oppressive Soviet regime, specifically those who were executed or died in the Gulag prison camp system.

Its work has come at a time when critics accuse the present-day Russian authorities of downplaying Soviet repressions.

These repressions, spanning from the early years of the U.S.S.R. to the Stalin era, saw widespread persecution, forced labor camps and political purges.

The Nobel Peace Prize-winning Memorial human rights group has listed at least 3 million victims of Soviet political terror, noting that the real figure could be up to four times higher.

In Moscow, Last Address plaques can be found on many streets in the heart of the city. Most of them commemorate those persecuted during the Great Purge in the 1930s.

Documentary director Oksana Matievskaya, who leads tours along the "Last Address" routes in the Russian capital, said that the situation with civil society in modern Russia echoes what happened here almost a century ago.

“By studying the past, we see that some stories nowadays unfold in the same patterns,” she told The Moscow Times.

Kindergarten teacher Yevgenia Voskresenskaya was accused of “maintaining close contact with a Greek correspondent, as well as with a Japanese correspondent.”

She was executed in 1937 and rehabilitated in 1989.

Professor and biochemist Alexander Kizel was executed in 1942 for treason. He was rehabilitated in 1956.

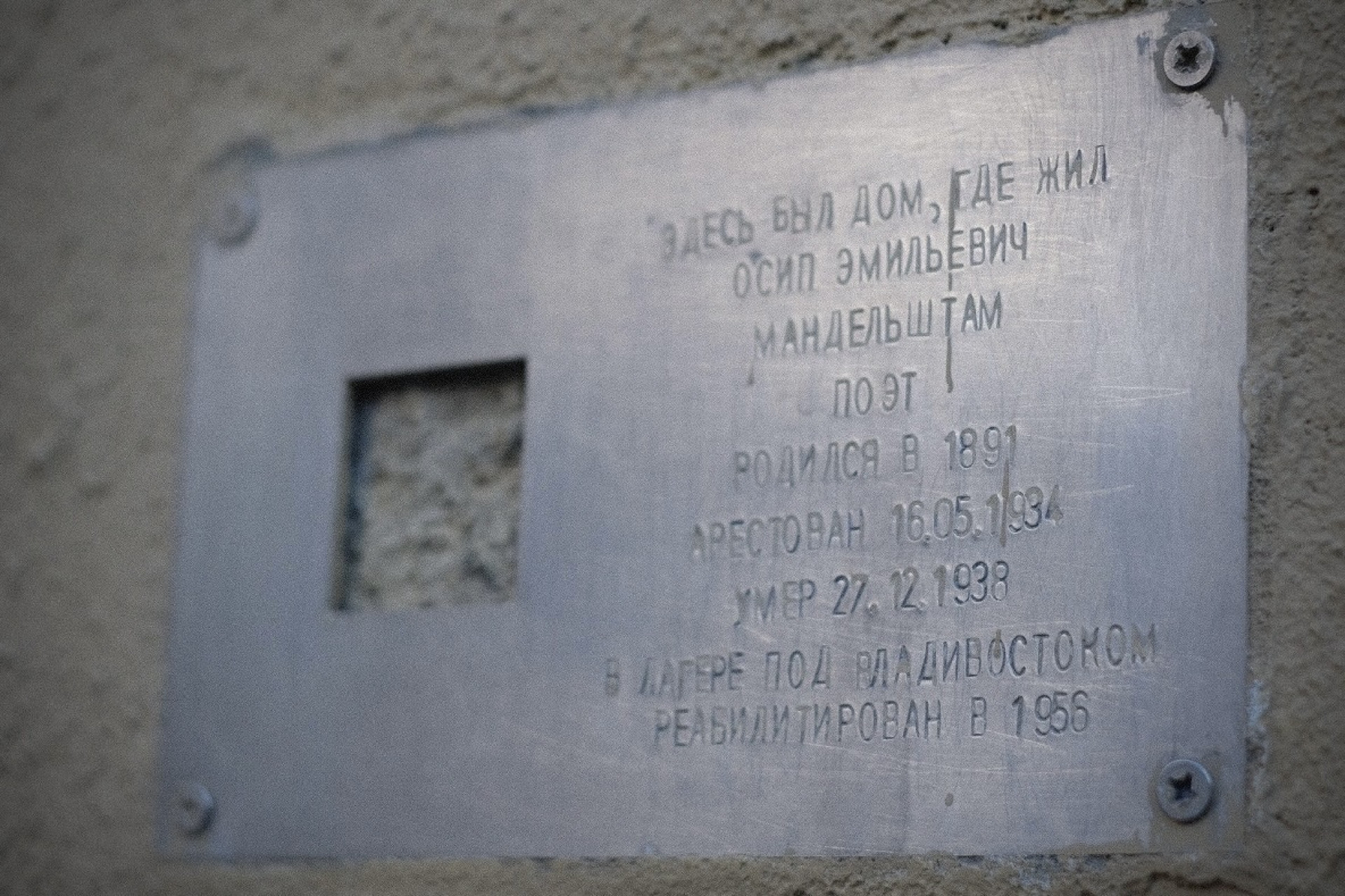

Osip Mandelstam, one of the most significant poets of the 20th century, was arrested in 1934 for his satirical poem “We live without feeling the country beneath us,” which was a criticism of Stalin. After his second arrest, he was sentenced to five years in a Gulag in the Far East, where he died in 1938.

Over the years, Last Address has installed more than 1,000 plaques in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other Russian cities.

For families and friends of those repressed, the installation of a plaque may be the only way to commemorate their loved ones — as in the case of the Tyutryumov family.

Sergei Tyutryumov’s daughter, Tatiana Tyutryumova, who was one month old when he was arrested, said her life’s goal “was to get at least some information and find out the burial place.”

Raised by her grandmother in Moscow, she moved to Tomsk in hopes of finding information about her father, who was falsely accused of being a member of an anti-Soviet organization and executed less than one month after his arrest.

Like Tyutryumov, between 928 and 2,801 people were executed on the same charges in Tomsk in the 1930s, according to various estimates.

Finding its place

The Last Address project draws inspiration from the Stolpersteine ("stumbling stones") initiative, which was created in 1992 to memorialize Holocaust victims in Europe.

Just as Stolpersteine involves placing small brass plaques in the pavement outside the victims’ last chosen residences, Last Address installs commemorative plaques on the buildings where the Soviet regime's victims last lived before their arrest.

These plaques bear the names, professions and birth dates as well as the date of their arrest, execution or death in the Gulag. The plaques are funded by private donations and their installation often involves a small ceremony attended by relatives and activists.

Despite the fact that every plaque installation must be approved by building management, and the names on the plaques are only those who have been officially rehabilitated, some buildings refuse to allow them.

Last year, Last Address also reported that some plaques had disappeared. In St. Petersburg, plaques were removed by order of the district administration following a denunciation. In Moscow, some plaques were removed as they “do not perpetuate the memory of outstanding events and figures of national history and culture,” the city administration said.

Rethinking history

Even amid Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, an intensified crackdown on independent voices and the forced closure of human rights organizations — including Memorial, which also works to preserve the memory of victims of political repression — Last Address stresses that it remains a crucial civil initiative.

“One of the reasons that repressions have returned to our lives again — let's be frank — that our history has not been properly reflected upon and not properly studied,” said Last Address tour guide Matievskaya.

“Our country will not move forward until we have put all the dots on the field, calling the criminals criminals and giving a proper assessment of that historical period,” Matievskaya told The Moscow Times.

While the Last Address project commemorates Soviet repressions, at least 739 people in modern Russia are currently facing prosecution due to their political views.

Moscow authorities refused to authorize a memorial event for victims of political repression last year, citing pandemic-era restrictions on public events.

Like Memorial, the Sakharov Center human rights group, opened to honor the memory of Soviet dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov, was forced to shut down.

In 2021, more than 100 public and cultural figures sent an open letter to President Vladimir Putin describing the problems faced by the children of victims of Soviet repression, who were still waiting for compensation for their families’ illegally confiscated apartments.

Answering the question of why it is important to continue working, Matievskaya said that Last Address "affirms the value of human life, regardless of merit, achievements, or positions one occupied."

"We emphasize that human life is priceless, and the state has no right to take it,” Matievskaya told The Moscow Times.

"We emphasize the irreplaceability of every life lost."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.