Most of Russia is set to experience prolonged periods of "high" and "extreme" wildfire danger this year, the state Hydrometeorological Center has forecast based on climate and weather data.

However, limited state capacity for fire prevention and control, along with ongoing practices such as dry grass burning, risk turning the annual peak wildfire season into a crisis, experts and firefighters told The Moscow Times.

“The overall forecast for the upcoming season is rather alarming,” Grigory Kuksin, an expert at the Landscape Fire Prevention Center NGO, told The Moscow Times.

“It's unlikely that there will be fewer fires than last year, and it's doubtful that they will be managed better," Kuksin said.

Russia's wildfire season, which officially began in early March in eight regions, has already seen significant activity.

Six wildfires were reported in the Far East's Primorye region, including in the Land of the Leopard National Park. By mid-March, the Zabaikalsky region had reported 25 wildfires.

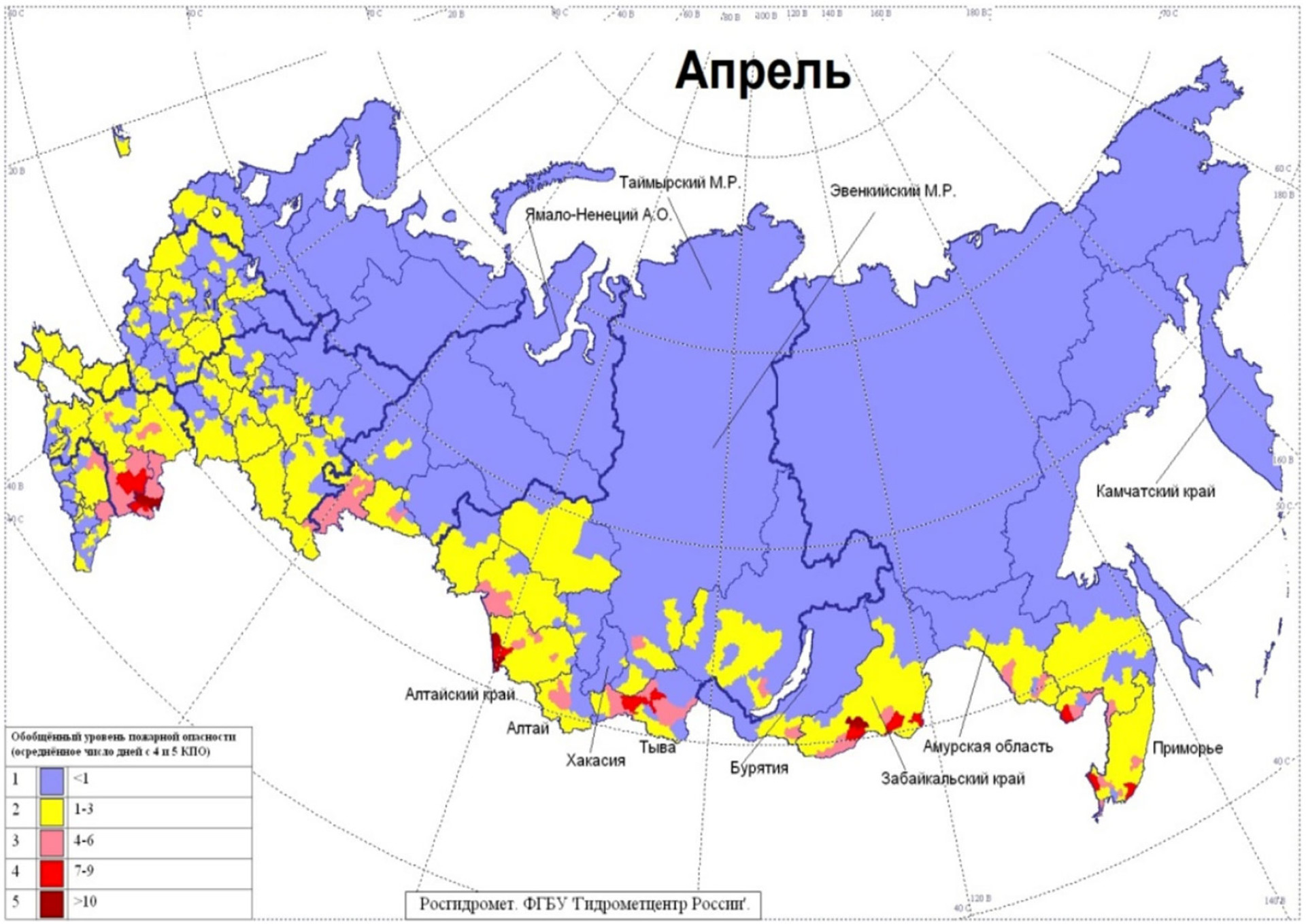

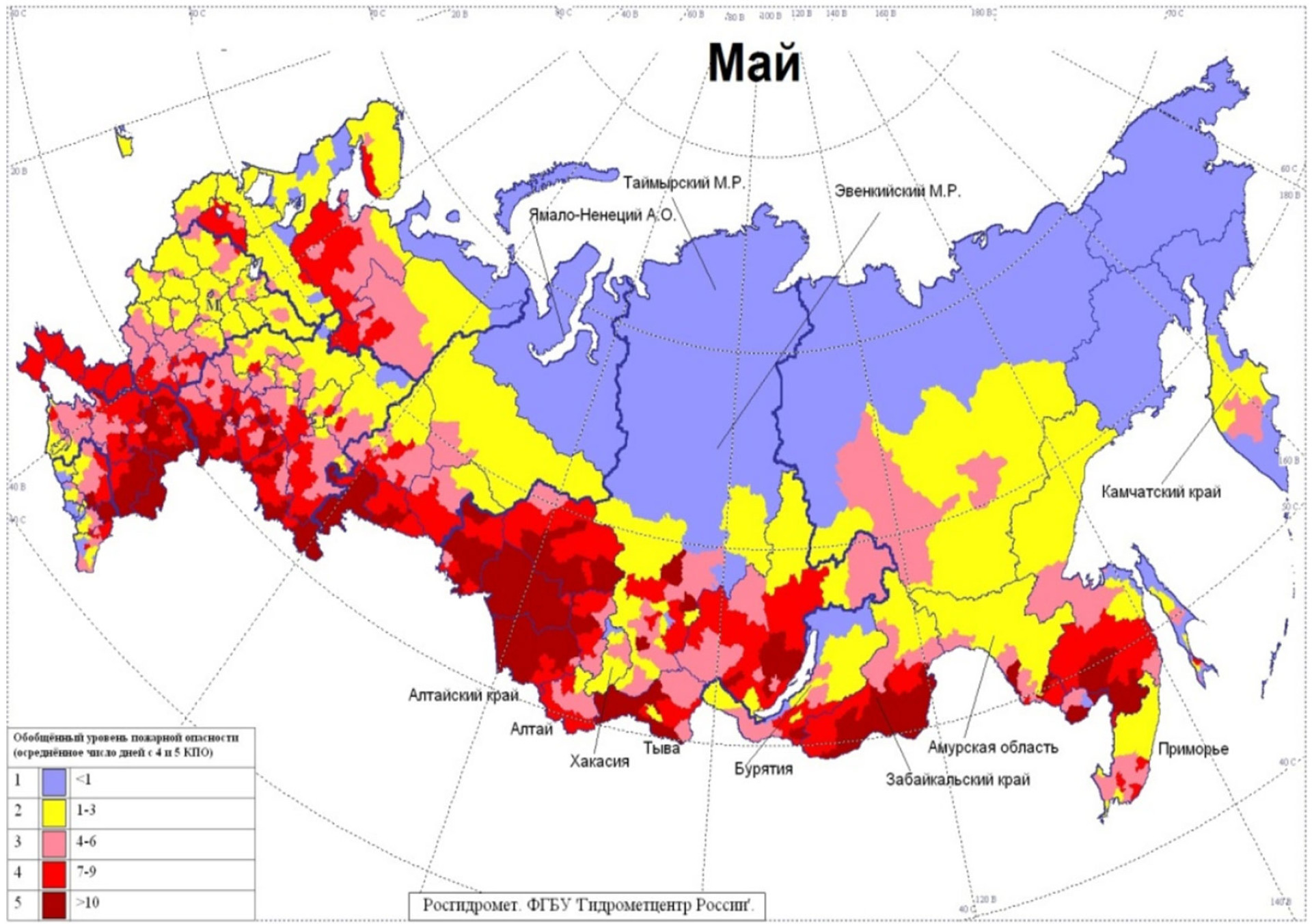

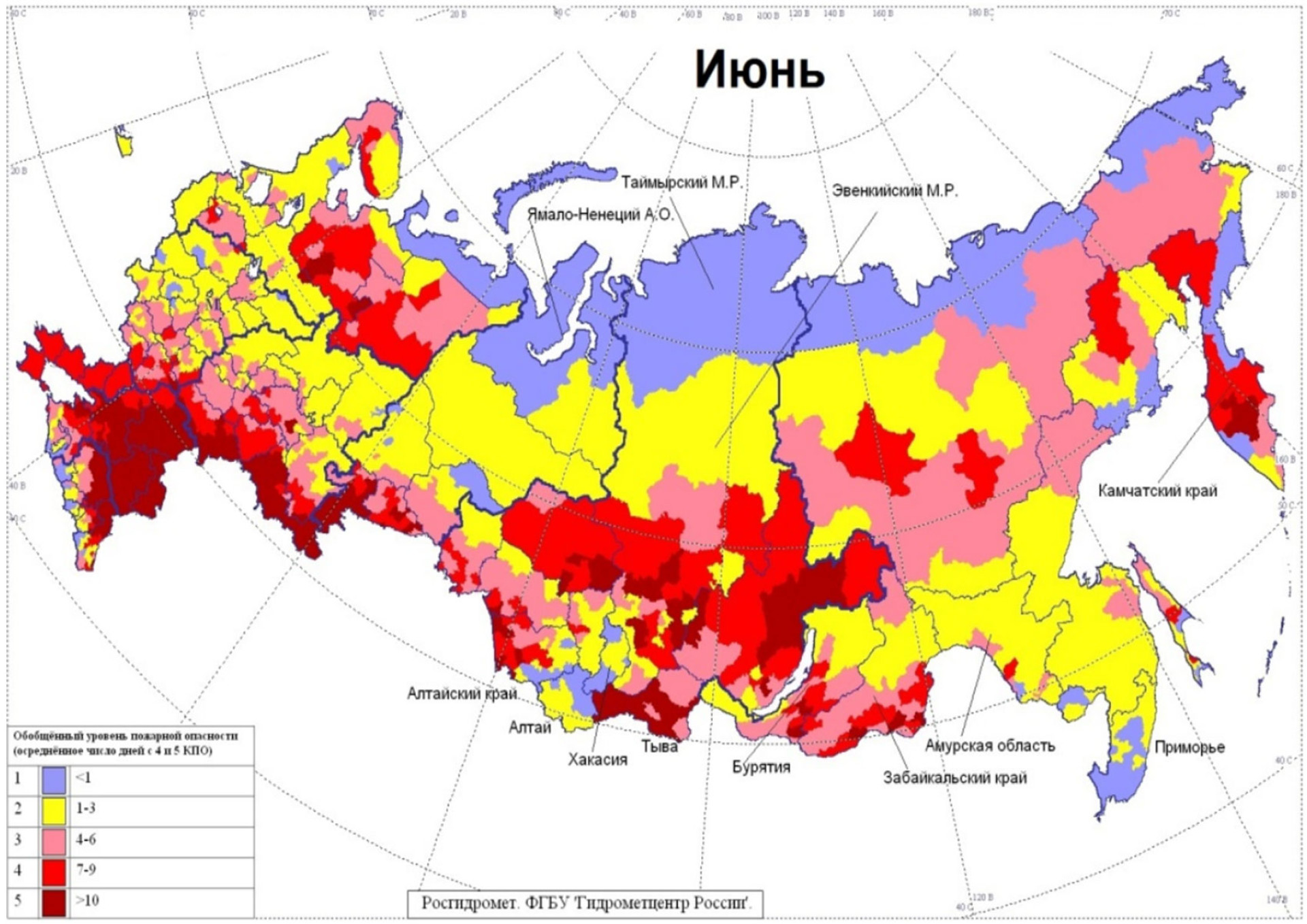

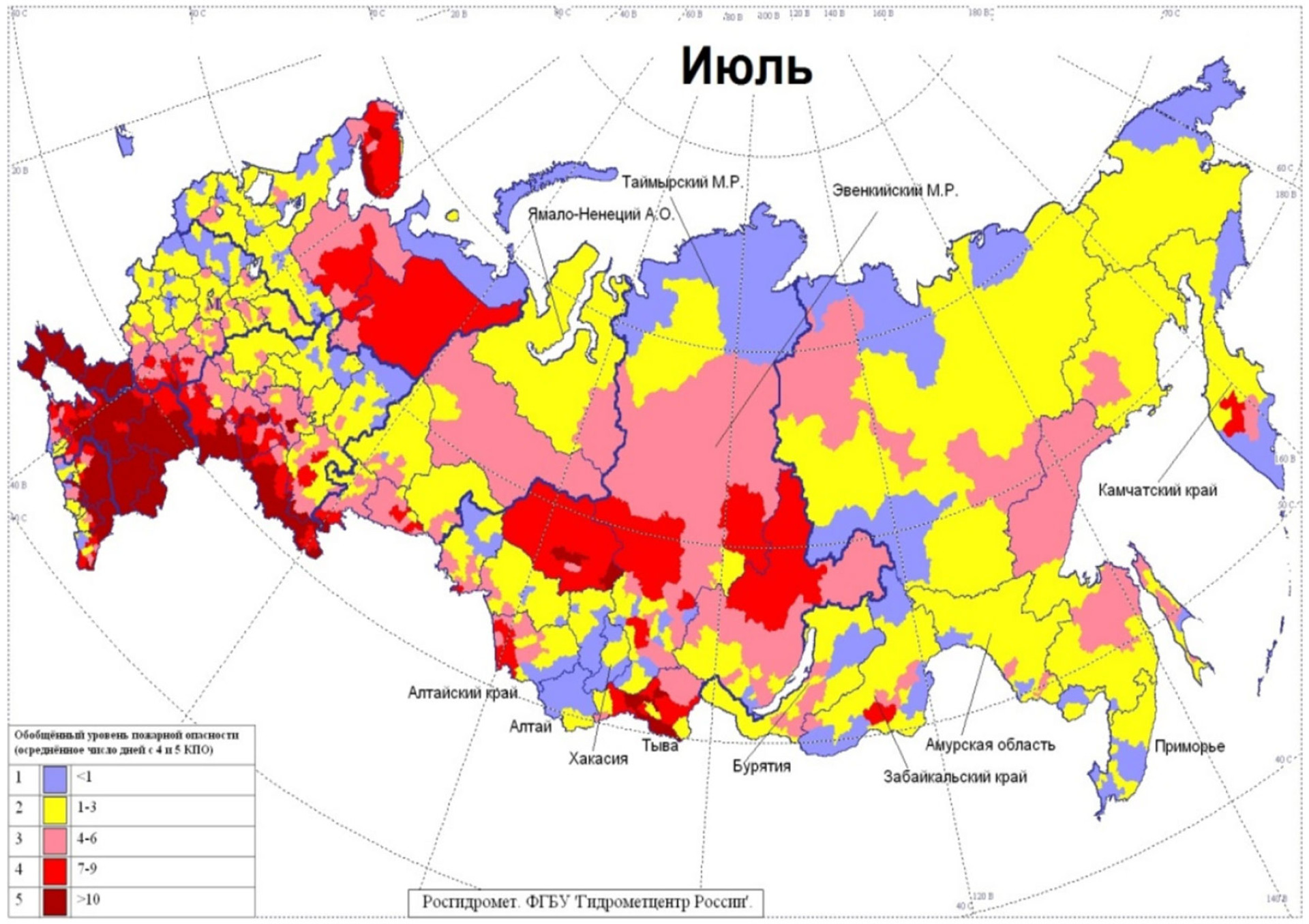

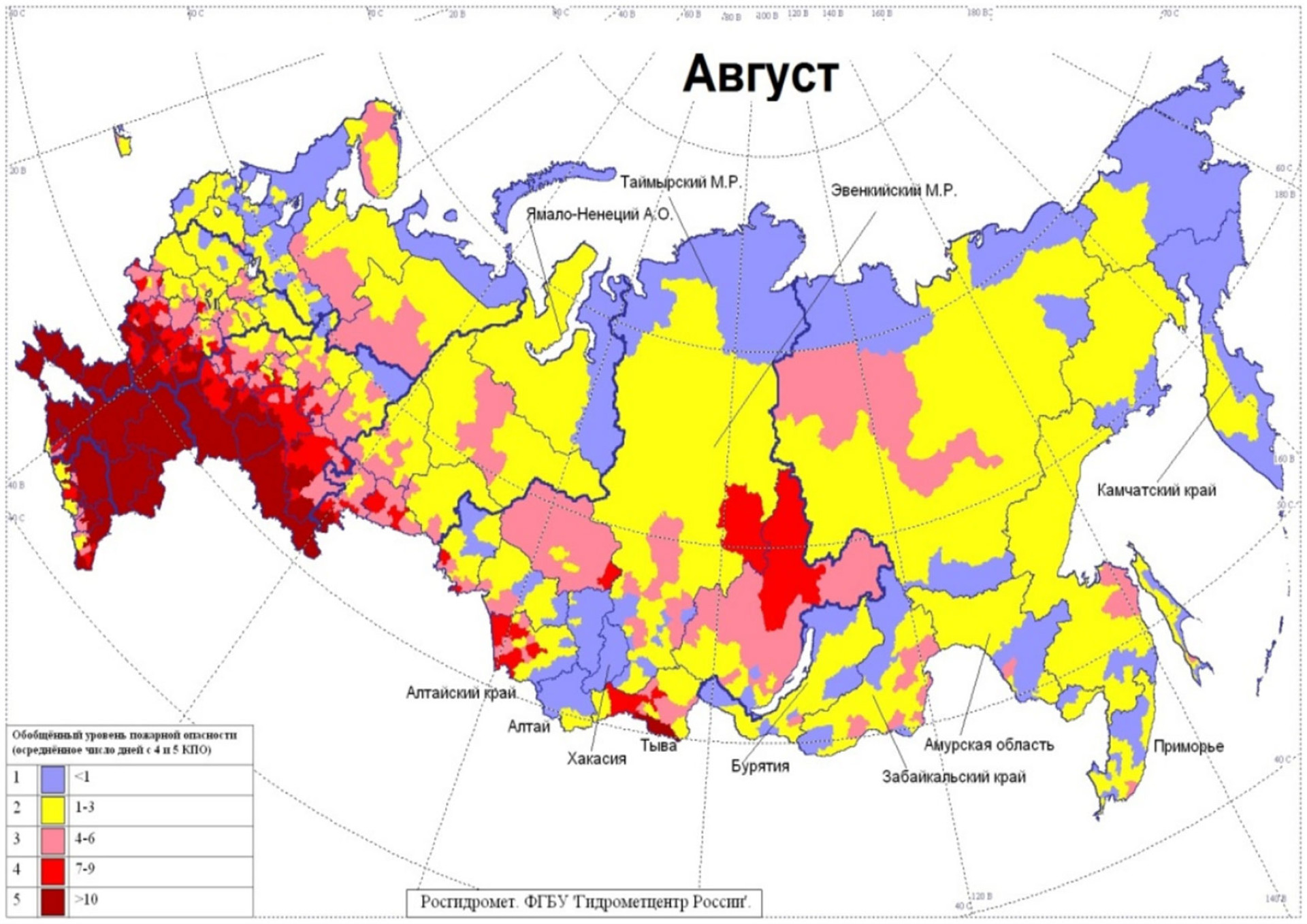

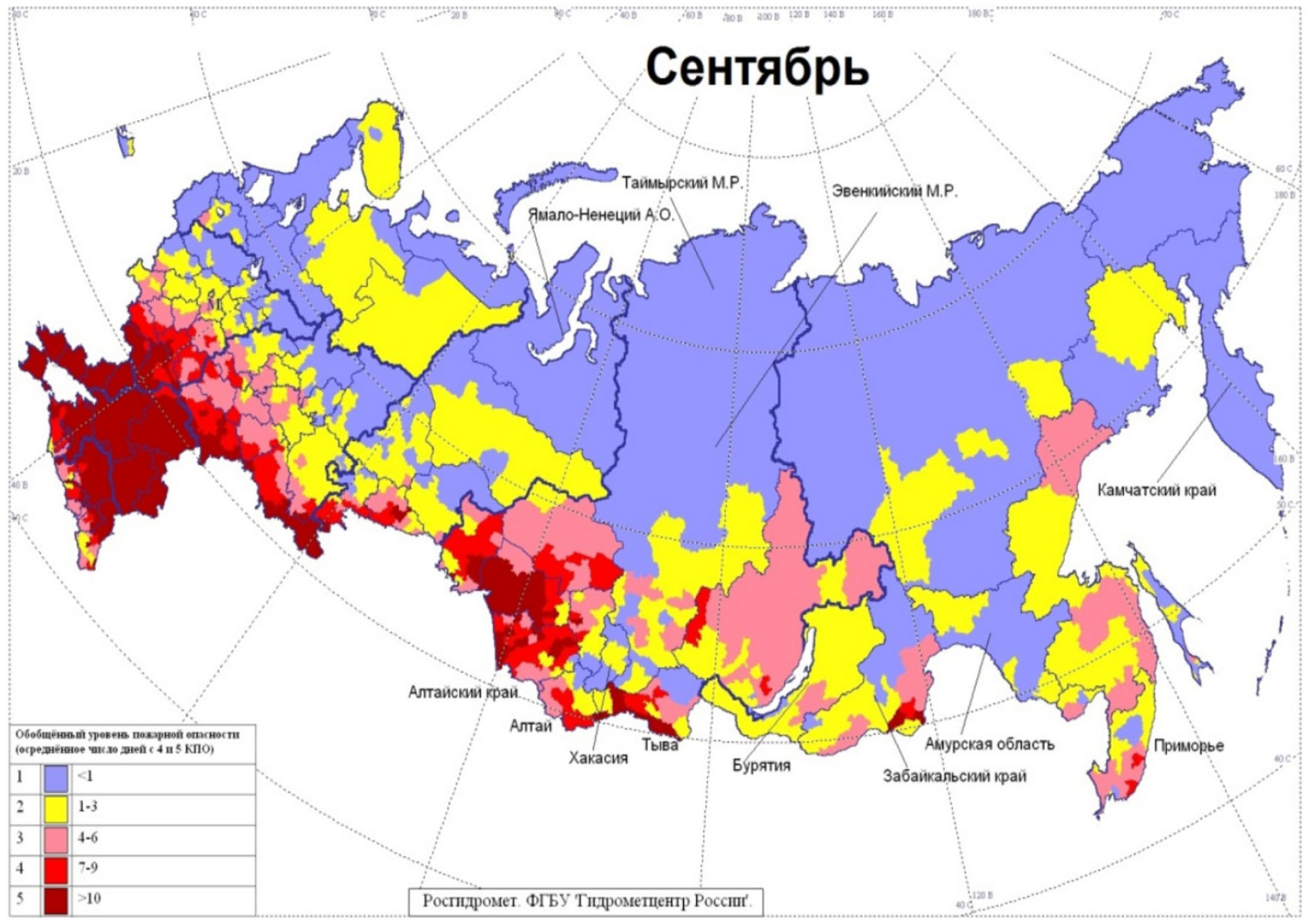

Wildfire risk increases as the country transitions out of winter, beginning in the southern regions in March. These risks are expected to reach the northern regions of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk by May and to cover almost the entire country by June, state forecast maps issued last month indicate.

Colors on the maps represent the number of days a region is projected to experience "high" and "extreme" fire danger during a particular month: blue — less than one day, yellow — 1-3 days, pink — 4-6 days, red — 7-9 days, dark red — over 10 days.

Though Kuksin said the 2024 state weather center’s forecast is “quite typical,” he warned that traditional land use practices and the habits of ordinary Russians would also influence the actual spread of fires.

For example, the burning of reed thickets and agricultural residues often leads to wildfires, even in subzero temperatures. Such incidents are expected in the Astrakhan, Volgograd and Rostov regions in March, despite these areas not being highlighted on the forecast map.

By May, as warm weather arrives in most regions and many Russians travel to the countryside and have barbecues during public holidays, the fire risk normally rises. The risks escalate further due to the habit of burning dry grass — a long-standing practice outlawed in 2015 but still in wide use.

“Even in the summer, when some fires are caused by storms — which are becoming more frequent in a changing climate — nine out of 10 fires are still caused by human activity,” Kuksin said.

He said he anticipates a particularly high number of fires in areas where fire is commonly used, such as logging areas and northern regions where pastures are burned.

Furthermore, a decline in groundwater levels across many Russian regions has Kuksin bracing for a "very challenging season," mirroring the difficulties of previous years.

Yet for those on the frontlines of fighting these fires, the battle feels neverending.

Zombie fires

For volunteer firefighter Anastasia from Yekaterinburg, the capital of the Ural Mountains region of Sverdlovsk, winter is a crucial time for addressing the smoldering threat of peat fires before they become a larger hazard.

These peat fires, often referred to as “zombie fires,” smolder beneath the snow from the previous year's wildfires and can quickly spread with the arrival of warm, dry conditions.

"At our place, the season lasts all year due to wintering peat fires," said Anastasia, who became a volunteer after devastating wildfires hit the Sverdlovsk region in 2021, opening her eyes to the threats faced by nearby green areas.

Anastasia is now part of a vast network of volunteer firefighters who aid the efforts of the chronically underfunded and understaffed government fire services.

Her name has been changed due to potential repercussions from speaking to foreign media.

In 2023 alone, her volunteer group was called out to the fields 53 times, she told The Moscow Times.

This winter, Anastasia and her group teamed up with workers from a state agency to extinguish a “huge and very problematic” peat fire in a settlement two hours away from Yekaterinburg.

According to Kuksin, zombie fires, once seen as an exotic phenomenon, have become a common challenge in Russia. This has prompted firefighters to brace for new and dangerous types of fires as climate change progresses.

In February, Sverdlovsk regional authorities said that they discovered 50 hotspots of smoldering peat, which could flare up with the onset of warmer weather. Governor Yevgeny Kuyvashev tasked officials with extinguishing all peat fires before the start of the wildfire season.

Despite the deployment of an effective technique for suppressing peat fires during the winter — a more cost-effective strategy than combatting large blazes later on — Anastasia said that some of the region's zombie fires may remain unextinguished.

Shifting the blame

Regional officials boast that their firefighting capabilities, in terms of fire trucks and equipment, exceed federally mandated norms by 114% and 145%, respectively.

Yet Anastasia said there are significant shortages in the human and financial resources needed for effective fire prevention.

With over 90% of Russia’s wildfires caused by human activity, Anastasia said she believes that regional authorities should ramp up public awareness efforts, as some citizens often pass the buck for wildfires to external actors.

“Somewhere in public transport, there is a scrolling message: ‘Don't burn.’ In some settlements, it’s broadcast on the radio ... But that's not enough,” Anastasia said.

“When everything starts burning, there are still people who say that it’s some Ukrainian saboteurs who came and started the fire. And they don't realize that it was themselves who threw a cigarette butt, and that's what caused the field and the forest to burn.”

This situation is exacerbated by last year’s unprecedented drought in the Sverdlovsk region, raising concerns about what the 2024 season could bring once in full swing.

“Unfortunately, we also have bodies of water disappearing completely: lakes are drying up, rivers are turning into mere streams,” Anastasia said.

“And this problem is becoming more and more relevant for all those marshy areas that have always withstood this human load associated with bonfires and [unextinguished] cigarettes. … Now any flame in the forest turns into a wildfire.”

Gearing up

As Russia braces for another potentially difficult wildfire season, officials are rushing to highlight their readiness efforts.

The regions have already put in place about 1,100 forest fire stations, 170 aviation units, 860 observation towers and over 480 aircraft, Russia’s Forestry Agency said.

"Winter has officially ended, and the first forest fires are being recorded. ... Most of them are … arising from a failure to comply with fire safety rules. Regional heads should closely monitor the situation," Alexei Venglinsky, the deputy head of Russia’s Forestry Agency, said in early March.

Kuksin said that recent legislative changes should enable quicker responses to wildfires, including the mobilization of additional forces and mandatory response to hotspots previously allowed to be ignored.

At the same time, the lack of significant funding increases for forest protection means that state firefighters must tackle larger-scale fires without adequate financial support, he said.

Low salaries also contribute to staffing shortages in many regions.

Yet overall, there appears to be no fundamental breakthrough either for the better or for the worse in Russia's organization of its firefighting force, the expert said.

Despite the troubling outlook for this year’s wildfire season, Kuksin said there are still ways to mitigate the damage.

“We need to burn less dry grass and tell people about the causes of fires and what each of us can do. We need to help detect and extinguish fires in time and to assist firefighters and volunteers,” he said.

“Much is still in our hands.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.