“I miss Komi, I miss Syktyvkar. I even thought about coming back, but I realized that I would be coming back to jail,” said Valera Ilinov, an exiled native of Russia’s republic of Komi, located about 1,000 kilometers northeast of Moscow.

His reservations about returning home are not unwarranted.

Last month, the 24-year-old founder of Komi’s flagship independent news outlet Komi Daily was fined for violating Russia’s censorship laws twice in one week.

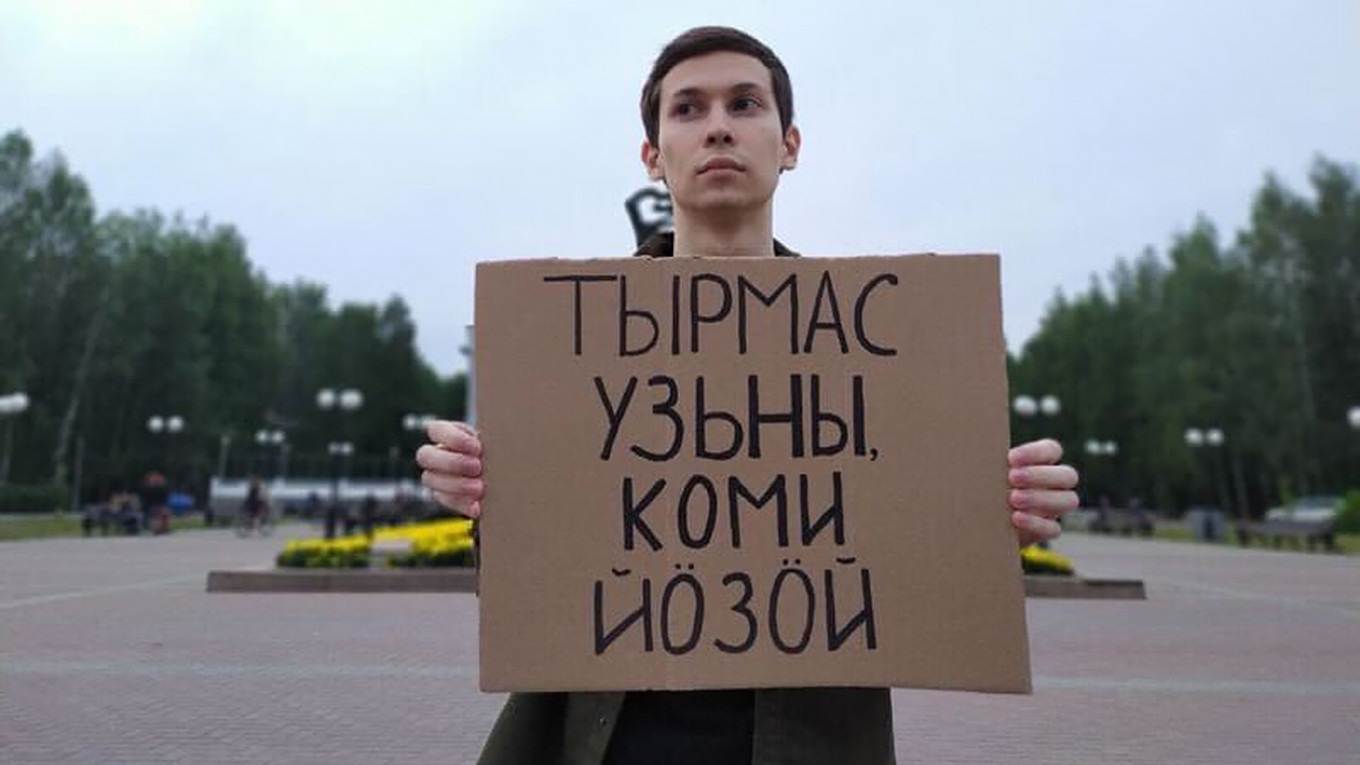

On May 30, Komi’s Syktyvdinskiy district court fined Ilinov 30,000 rubles ($337) for “discrediting” the Russian military in an anti-war statement published by Komi Daily that marked nine years of the war in Ukraine. If convicted of a repeat offense, Ilinov, who now lives in Germany, would face up to five years in jail.

A week prior, the same court had fined Ilinov 10,000 rubles ($112) for “inciting hatred or hostility toward Russians.”

“There is a character description in that case which states that I am ethnically Russian,” said Ilinov, who identifies as Komi, a Finno-Ugric ethnic group native to the republic of the same name and parts of the neighboring Perm region with a population of less than 144,000.

“So according to the FSB, I'm Russian and I'm inciting hatred towards Russians. I even joke that it's an internalized Russophobia of sorts,” Ilinov said with a laugh.

“But I was upset because this fine wasn't even related to our content,” he added. The case was linked to a column by anthropologist Vasilina Orlova titled “Instructions on Changing an Imperial Mindset” originally published by the Kit media newsletter.

Born and raised in Komi, Ilinov said his interests in journalism and his heritage date back to the events surrounding Ukraine’s 2013-2014 Revolution of Dignity, which he started following after his favorite Ukrainian rock band, Okean Elzy, performed for the thousands of protesters gathered on Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti.

“There was this [Russian propaganda] discourse about Russian-speaking people being oppressed in Ukraine and calls to ‘save’ them — that’s when I started questioning who I am,” Ilinov recalled in a conversation with The Moscow Times.

“I was born and raised in the republic of Komi, some of my ancestors were Komi. Despite my family being fully Russian-speaking, I was surrounded by the Komi language, culture and mythology since childhood. Eventually…I realized that I am more Komi [than Russian],” said Ilinov.

Ilinov’s emerging interest in his Komi identity motivated him to study the Komi language, which is not widely taught in his home republic as Russians are the majority ethnic group.

His interest in politics, in turn, led him to take part in late opposition politician Alexei Navalny’s nationwide anti-corruption protests in his hometown of Syktyvkar in June 2017, when he was just 17.

Yet Ilinov did not join the rapidly growing Navalny movement, instead choosing to work with the prominent youth activist group Vesna and then the St. Petersburg youth wing of the liberal opposition party Yabloko. He soon realized that Russia's power vertical allows for almost no change at the grassroots level.

“I had burnout from engaging in politics without getting anything in return, seeing no results, no changes. I was disappointed…so I left [the party]," said Ilinov.

In September 2018, he created a page on the popular Russian social media network VKontakte titled Komi Daily.

"I wanted to read a media that writes about Komi culture — especially modern Komi culture — and the Komi language. But since there was no such media outlet and it was unlikely that one would ever be created, I decided to create it myself,” he recalled.

"The main audience I wanted to reach was people like me, those with Russian-speaking families who initially lacked Komi identity,” he said.

What started as Ilinov’s personal blog soon became a fledgling media outlet, gaining thousands of followers on VKontakte, expanding to other social media platforms and eventually launching a website.

But the most dramatic change for Komi Daily, which describes itself as “decolonial media about Komi culture and identity,” came with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In addition to sparking a severe crackdown on dissent and independent media, the invasion triggered widespread interest in Russian colonialism and the country’s non-Slavic Indigenous communities.

Ilinov said he sees “decoloniality” as adhering to a set of “mostly left-leaning views” built from the principle of “nothing about us without us.”

“If we're talking about Komi Daily, then [decoloniality means that] someone connected to Komi participates directly in creating the article rather than just being a voice featured in it,” he said.

After the invasion, Ilinov was joined by a group of equally enthusiastic volunteer journalists from Komi to expand Komi Daily’s coverage, but the outlet lost a significant chunk of its audience over its staunchly anti-war position. And in October 2023, Russian authorities blocked its page on VKontakte.

“A few of those who subscribed [since the start of the war] are connected to Komi,” Ilinov explained. “Our audience now are people from other republics, those interested in Komi and different Russian regions and ethnic groups, or people interested in diversity in general.”

Although Komi Daily lost readers after it voiced its political stance, Ilinov said he firmly believes that trying to produce “objective” or “apolitical” journalism in a climate of political repressions and war is no different from echoing Russian propaganda.

“There's inherently some activism in what I do because, otherwise, it would be unclear what we stand for, what values we promote, and whose side we are on,” he explained.

“It is impossible to be just a journalist and not an activist in modern Russia.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.