The cuisine of the Middle Ages is not a cuisine of pleasure or enjoyment. It is primarily a cuisine of satiation — simply getting enough to eat. That's why the efforts of modern nutritionists to find a role model in our ancient cuisine seem a bit strange.

Of course, a long time ago people realized that some combinations of foods not only filled a person but provided benefits. In general, however, plentiful food was the ideal of medieval life, and more often than not — a symbol of privileged status.

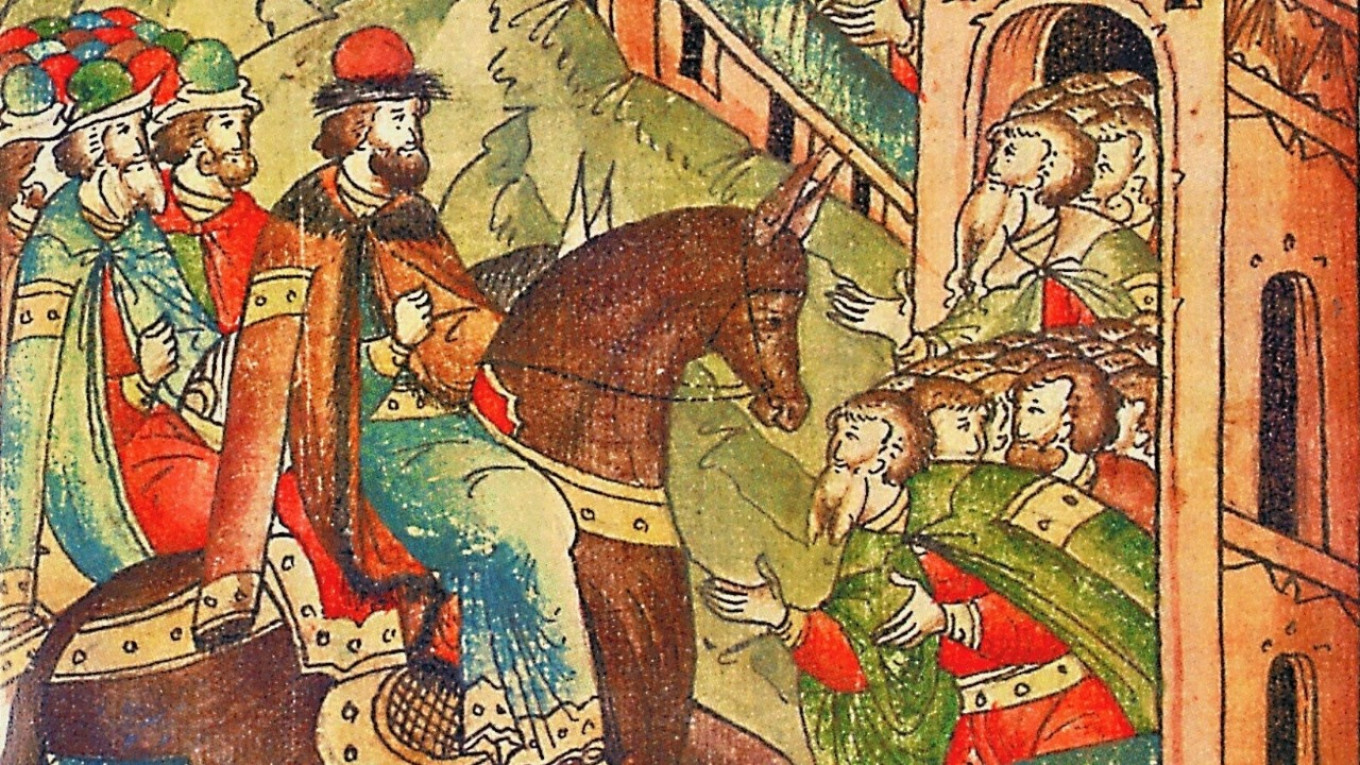

Nevertheless, seven to ten centuries ago overeating was probably an exception. It is hard to imagine an obese grand duke. “His height is not very great, but he is well-built and strong,” Russian historian Vasily Tatishchev wrote about Vladimir Monomakh (1053-1125). “Beautiful appearance, tall body,” he said of the Kyivan Grand Duke Izyaslav (1024-1078).

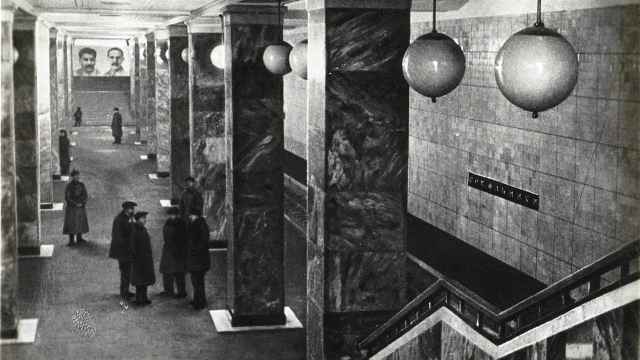

"You give feasts for the sake of your reign and power. When others eat and drink, you yourself only sit and watch,” Metropolitan Nikephoros told Vladimir Monomakh.

Monomakh’s continuous campaigns throughout Russia undoubtedly contributed to keeping in shape. These travels were a common feature of early feudal society. French historian Marc Bloch wrote about the European Middle Ages that “it was impossible to govern the state sitting in the palace; to keep the country in hand, the ruler had to travel around it constantly in all directions. The kings of the first feudal period literally did not get out of the saddle.”

That is why we don’t find overweight people among the images of ordinary townspeople or peasants of that epoch. Antique engravings such as those in the book by Adam Olearius “Description of a Journey to Muscovy and Through Muscovy to Persia and back” (1647), confirm this.

Women are, however, a different case. They have always cared about their beauty, and nutrition is one of the main factors. What was the daily menu of a Muscovite woman 150 years ago?

You might be surprised, but it is quite easy to establish. Russian cookbooks of the 19th century liked to provide menus for almost every day of the year. Here, for example, in Elena Molokhovets’ cookbook for 1901 is the list of “first category” dinners:

"French soup à la julienne served with pies filled with calves’ brains and puff pastries with minced meat or veal liver with Madeira. Viennese style beef fillet. Sterlet in champagne. Artichokes with green peas. Spinach pudding with crawfish necks. For the roast course: snipe, woodcock, partridge with salad. Crème royale, berries, fruit."

Of course, this is a menu for a well-to-do family, but not necessarily aristocratic. For example, a successful engineer or a senior officer of the Russian Navy could receive his friends with this sort of meal. After all, Elena Molokhovets’ husband was just a provincial architect, albeit probably a talented one.

An ordinary daily dinner in such a family might be like this one listed in the section “fourth category dinners”: “Botvinya (cold soup with fish and kvass). Duck with white sauce and potatoes. Plum jelly." Or this menu: “Broth of root vegetables and cauliflower. Broiled beef with macaroni and sour cream. Baked apples."

In other words, the typical menu didn’t differ too much from the home-cooked meals of today.

On the other hand, women even then made efforts to lose weight. Before balls young women specially drank vinegar to get an “captivating” pallor. And they wore tightly tied corsets.

This fashion was followed both by families far removed from medicine and by people who had a professional knowledge of nutrition. A sad example of this was Pelageya Alexandrova-Ignatieva, one of first authors of Russian cookbooks. When she was pregnant in the early 1900s she often wore a tight corset. Family legend has it that this was the cause of the problems that arose with her child. Her daughter Varenka was born with serious illnesses and died before she reached age 30. It was a terrible shame to loose such a talented and vital person, which we can see in her correspondence with Olga Knipper-Chekhova.

Many people today ask if there were “men’s” and “women’s” food and dishes in tsarist Russia. We know for sure that there was nothing of the sort in the peasant hut. The only difference with "women's food" was that women sometimes gave the best food to the head of the family and took was what left after he and the children ate. That was often not much at all.

Cooking in more affluent households made it possible to choose a lighter menu. But how shall we put it? The ideal of beauty in pre-Petrine Russia was never a pampered beauty with a tiny waist and marble skin. Our advice is to eat a delicious and varied diet. And if you need to diet, consult a doctor, not a cook. Everyone should stay in their own lane.

That said, the study of ancient cookbooks gives an amazing sense of how reasonable the nutrition of our ancestors was. In particular, the abundance of vegetables in the daily diet is striking. Even in the 18th century, vegetables or just lettuce leaves were served as an “accompaniment to fish or meat.” Boiled beets, carrots, radishes, turnips and celery were widely used along with beans peas, both in pods and shucked. They also served various kinds of of lettuce (sometimes made into a soup), sorrel and endive. The dressing was simple — mostly vegetable oil, vinegar, salt and pepper.

We will try to reproduce a similar salad — something simple, not requiring special or expensive ingredients. Serve with simply prepared meat, cooked in the oven or on an open fire... it’s quite delicious and, most importantly, very healthy.

Bean and Mushroom Salad

Ingredients

- 300 g (10.5 oz) green string beans

- 1 Tbsp olive oil

- 10 mushrooms

- 1 bunch of green onions

For the dressing:

- 75 ml (1/3 c) olive oil

- 75 ml (1/3 c) soy sauce

- 2 garlic cloves

- 1 Tbsp grated ginger root

- 1 Tbsp. honey

- pinch of ground chili pepper

- 2 tsp lemon juice

Instructions

- Wash the mushrooms thoroughly and chop them coarsely. Heat olive oil in a skillet and sauté the mushrooms for 5-7 minutes. Remove from the heat and cool completely.

- Pour the beans into boiling salted water, let boil and cook for 3 minutes. Remove from the pot with a skimmer and transfer to ice water. With this technique beans — as well as many other green vegetables such as asparagus and peas — retain elasticity and bright green color.

- Prepare the dressing: peel garlic, chop, mix with olive oil, soy sauce and honey.

- Add ginger, chili pepper and lemon juice. Place the beans and cooled mushrooms in a salad bowl, pour the dressing over them and mix.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.