In the Soviet period food didn’t get much public attention. Like the rest of daily life, it paled in the glow of lofty communist philosophy. But that's strange. It would seem that the topic would be perfect to blot out memories of the “glorious” past. After all, food riots in Russia were precursors to the proletarian revolution.

Through all that, one dish somehow became a symbol of Russian cuisine. It is simple, quick, and can even be made by an inexperienced home cook. But its history is not old at all. And its taste is a legacy of war.

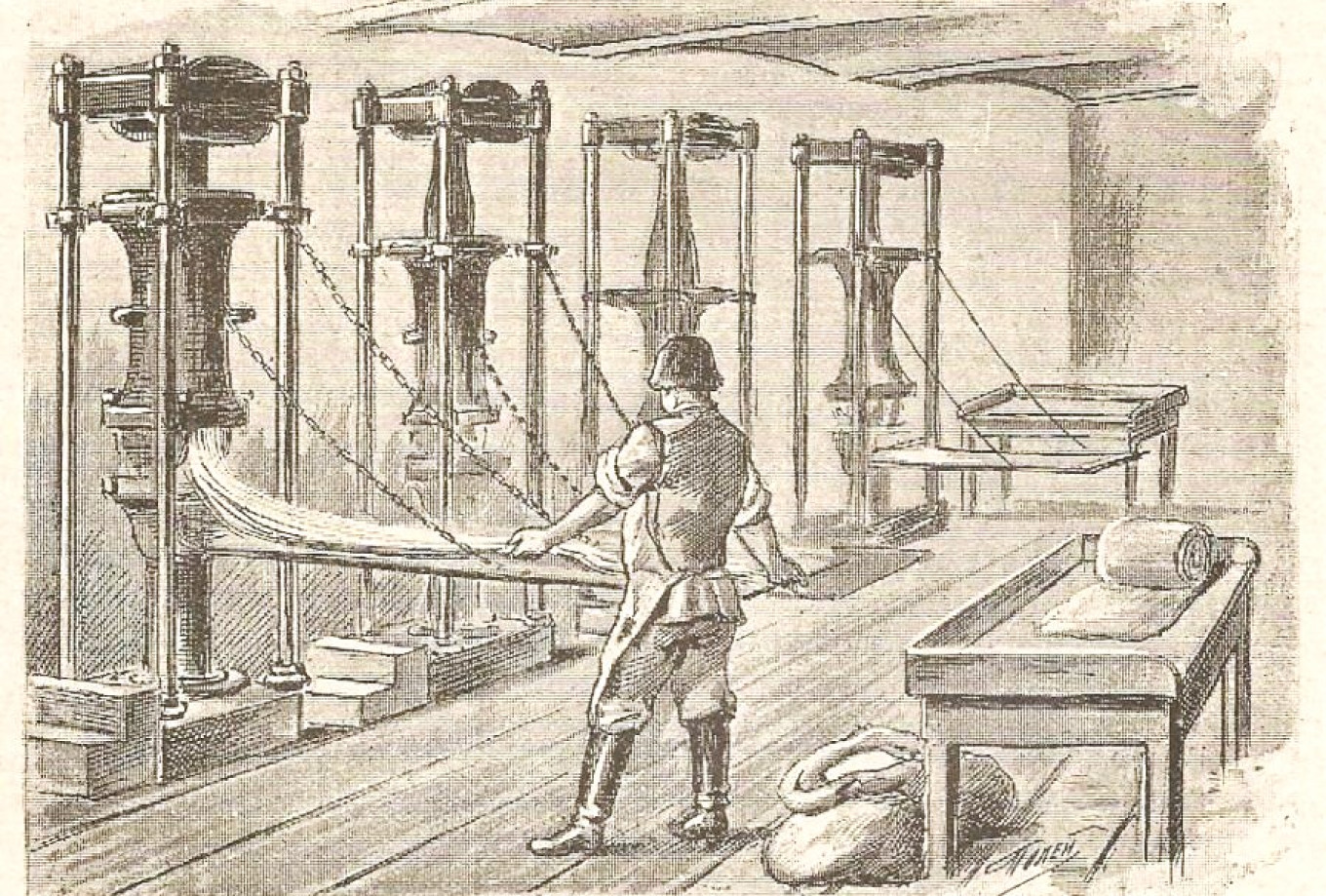

Macaroni became famous in Russia in the late 18th century thanks to Grigory Potemkin. In Odessa in 1797 he opened the first factory producing this unusual product. To be fair, the word “factory” is a bit of a misnomer, because almost everything was done manually. Macaroni was dried in the sun and then moved indoors at night. The first machine for drying spaghetti would be invented in Italy only 15 years later.

All the same, the new dish became popular even among Muscovites. For example, the owner of the Muranovo estate near Moscow, General Lev Engelhardt, in 1811 gave his cook a written order to buy “3 pounds of macaroni” to celebrate his birthday. Today this handwritten note is preserved in the Lobachevsky Library at Kazan University.

But how was macaroni prepared then? Probably like in this recipe from the ancient book “The Paris Cook, or A Cookbook Containing Everything Related to City Cuisine,” which is in the library of the Muranovo estate near Moscow:

“Boil a pound of macaroni in a good broth with salt, pepper and grated nutmeg. You must not boil the macaroni too long, but to the point where you can squeeze a strand with your fingers. Take the macaroni out and let it drain. Then put the macaroni in a saucepan with a quarter pound of butter, half a pound of chopped cheese, coarsely ground pepper and grated nutmeg. Mix it all well and add a little sour cream.”

It is clear that this dish is nothing like the familiar dish Marine Macaroni. In general, there is a misconception that Marine Macaroni came to us from Italy. There is one version that Russian sailors in the 19th century were introduced to this tasty dish in their travels to that country. Alas, as is often the case with culinary stories, this is pure fiction.

Italians typically eat spaghetti with tomato sauce. With a great stretch of imagination you might find an Italian dish similar to Soviet Marine Macaroni: Spaghetti Marinara is pasta with a sauce made of tomatoes, garlic, onions, oregano, capers and olive oil.

On the other hand, the product itself — fresh or dried pasta — did really came to Russia from Italy. The first experiments with pasta production in Russia were undertaken by Italians about 200 years ago. But a professional factory with drying was opened in Moscow only in 1883.

Macaroni would seem to be a prime example of mass-produced democratic food: convenient, easy to store, quick to prepare. But there was one problem: Macaroni was expensive. One pound cost from 9 to 14 kopecks, which was about the same price as a pound of meat. Before the 1917 Revolution, macaroni was mostly an elite treat for the well-to-do. The only exception was for naval crews who were served it on voyages even before World War I.

Sailors were well fed as a reward for their grueling work. They weren’t served simply macaroni, but macaroni with finely chopped, cooked meat. This was a delicacy within a delicacy.

Sailors on the battleship “Gangut” were exhausted after loading tons of coal onto the ship. Suddenly they learned that today they’d just get porridge. But the unwritten law-of-the-sea was that after hard work the crew would be served a tasty meal of macaroni and meat. The sailors revolted, and it took a day to calm them down.

Was this the first version of Marine Macaroni? Actually — no. In those years the macaroni dish was prepared in a different way. The macaroni was boiled separately and then served with meat that had been spooned out of pots of borscht and chopped up.

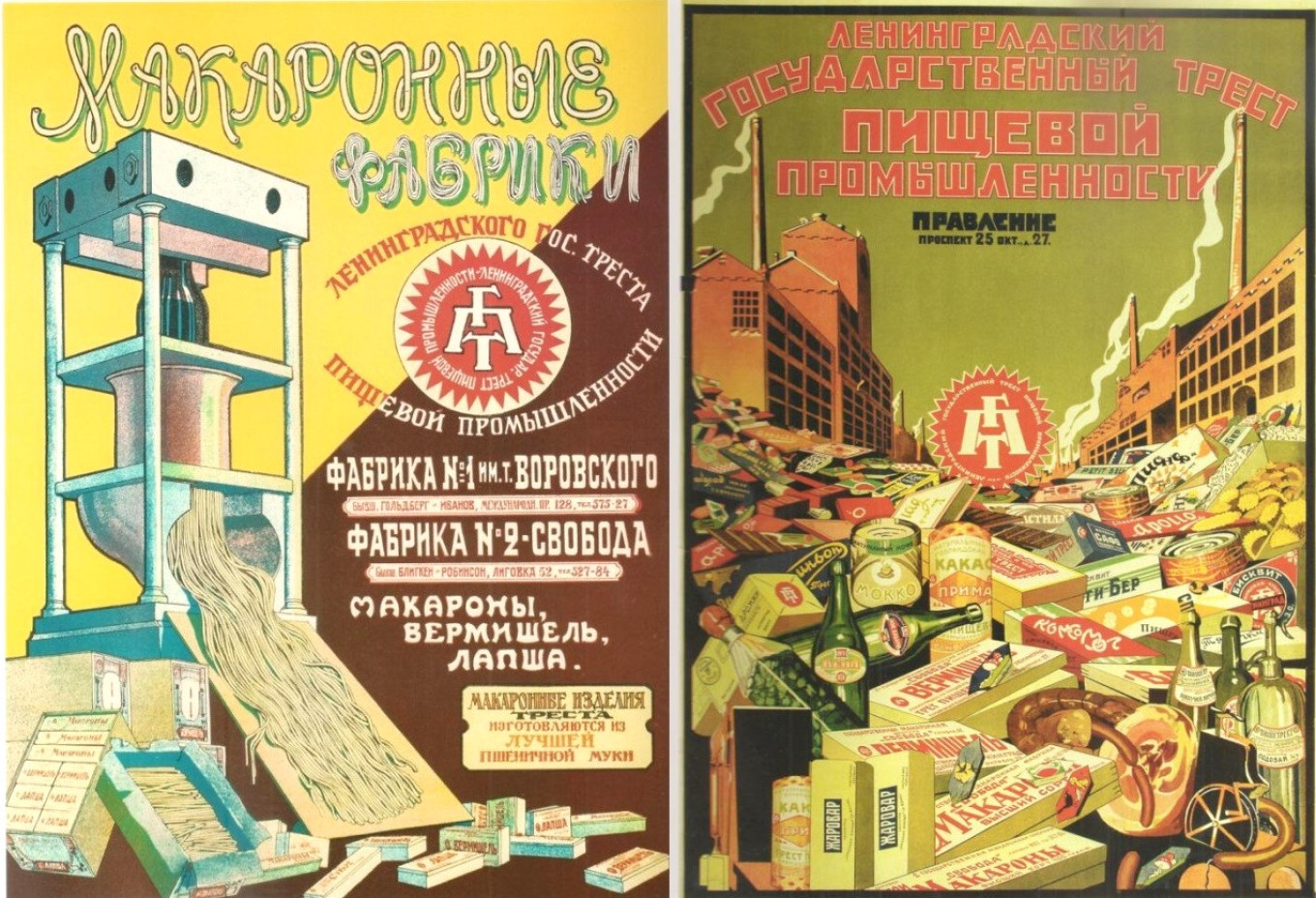

Needless to say, the subsequent revolution and devastation almost erased memory of this dish. Macaroni returned to Soviet kitchens in the mid-1920s, when pasta factories were opened. But no cookbook during this period mentions Marine Macaroni.

The dish came to the USSR during WWII when macaroni appeared in millions of rations and front-line canteens. And the American second front tinned meat — Spam — became the perfect complement to “combat spaghetti.” Apparently this now-classic recipe originated in Murmansk, the capital of the Northern Fleet.

Classic Marine Mac 'n' Meat

Ingredients

- 400 g (scant lb) penne, elbows or other macaroni

- 400 g (scant lb) boiled beef

- 150 g (5 oz) onions

- 100 g (3.5 oz or ½ c) butter

- salt, ground black pepper

Instructions

- Put the boiled beef through a meat grinder.

- Dice onions finely and sauté in half of the butter.

- Boil the pasta until cooked, drain, add butter, mix.

- Put the pasta and minced meat in the pan with the sauteed onions. Stir.

- Serve with sour cream.

The war finally came to an end, but the Soviet people, accustomed over the years to fast and easy simple dishes remember the past warmly even in peace time. After the country finished up Lend-Lease Spam over the course of several more years, they had home-made Soviet canned meat — which was just as popular. Of course, it could be spread on bread. But it tasted better with macaroni!

This recipe has turned into one of the most popular recipes in the country, both in the home kitchen and in cafeterias. Of course, this is not a refined restaurant dish. On the contrary, it's from everyday life, post-war, when people longed for any kind of feast.

Marine Macaroni appears in cookbooks is only in the 1960s. That’s when it became an easy fallback meal for both experienced and inexperienced or lazy home cooks as well as for the majority of cafeterias.

But there is a curious historical analogy with macaroni and revolution. A few years ago, Natalia Sokolova, Minister of Labor in the Saratov administration, proposed that the the cost of the regional consumer basket not be changed. At the time is was 3,500 rubles or 55 dollars. In response, one of the local deputies (back then it was still possible to disagree with the authorities) said that “feeding a donkey in the Leningrad zoo costs 10,600 rubles a month, and a ferret — 2,700.”

“It is necessary to eat a balanced diet,” the minister replied. “Based on the prices in discount stores. You’ll see that you can live on it — and become younger, more beautiful and slimmer! Macaroni always costs the same!”

Maybe Putin needed this war to distract people from the fact that “macaroni” is no longer affordable. After all, the Russian authorities are afraid of the “glorious revolutionary past.”

Today we make this dish in a slightly new way that is tastier, brighter, and more interesting.

Revised Marine Mac ‘n' Meat

Fried meat is much tastier than boiled meat — everyone knows that. Of course, frying results in a crust, which is what gives the meat its more intense flavor and aroma.

Ingredients

- 400 g (scant lb) penne, elbows or other macaroni

- 500 g (generous lb) beef

- 150 g (5 oz) onions

- 100 g (3.5 oz or ½ c) butter

- 1 clove garlic

- salt, ground black pepper

Instructions

- Cut the meat into 2x2 cm (1”x1”) cubes and put it through a meat grinder.

- Dice the onions, mince the garlic and sauté in half of the butter.

- Add minced meat and, breaking up with a spatula; sauté for 10-12 minutes. Salt and pepper to taste. To make the minced meat smoother, when cooking, you can pour 1/3 cup of water and cook until the liquid evaporates.

- Boil the pasta until ready in salted water.

- Drain the water, add the remaining butter to the pasta and stir.

- Add pasta to the pan with fried minced meat.

- Serve with sour cream. You can add a little pressed garlic to the sour cream. Sprinkle with cilantro, dill or parsley.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.