After living for two weeks in a psycho-neurological internat, a facility where Russia confines those with psychiatric illnesses who have no relatives willing to care for them, journalist Elena Kostyuchenko believed she had seen the “real face of my state.”

She spoke to women who were forcibly sterilized, showed a doctor poetry written by a patient in an attempt to demonstrate the patient was not in the “vegetative” state their medical records claimed, and watched as female residents scrambled for their daily allocation of cigarettes.

“When human connection is lost, all that is left is the state,” Kostyuchenko writes. “My state is the internat. Not the Sputnik V vaccine, not the Olympics, not space shuttles.”

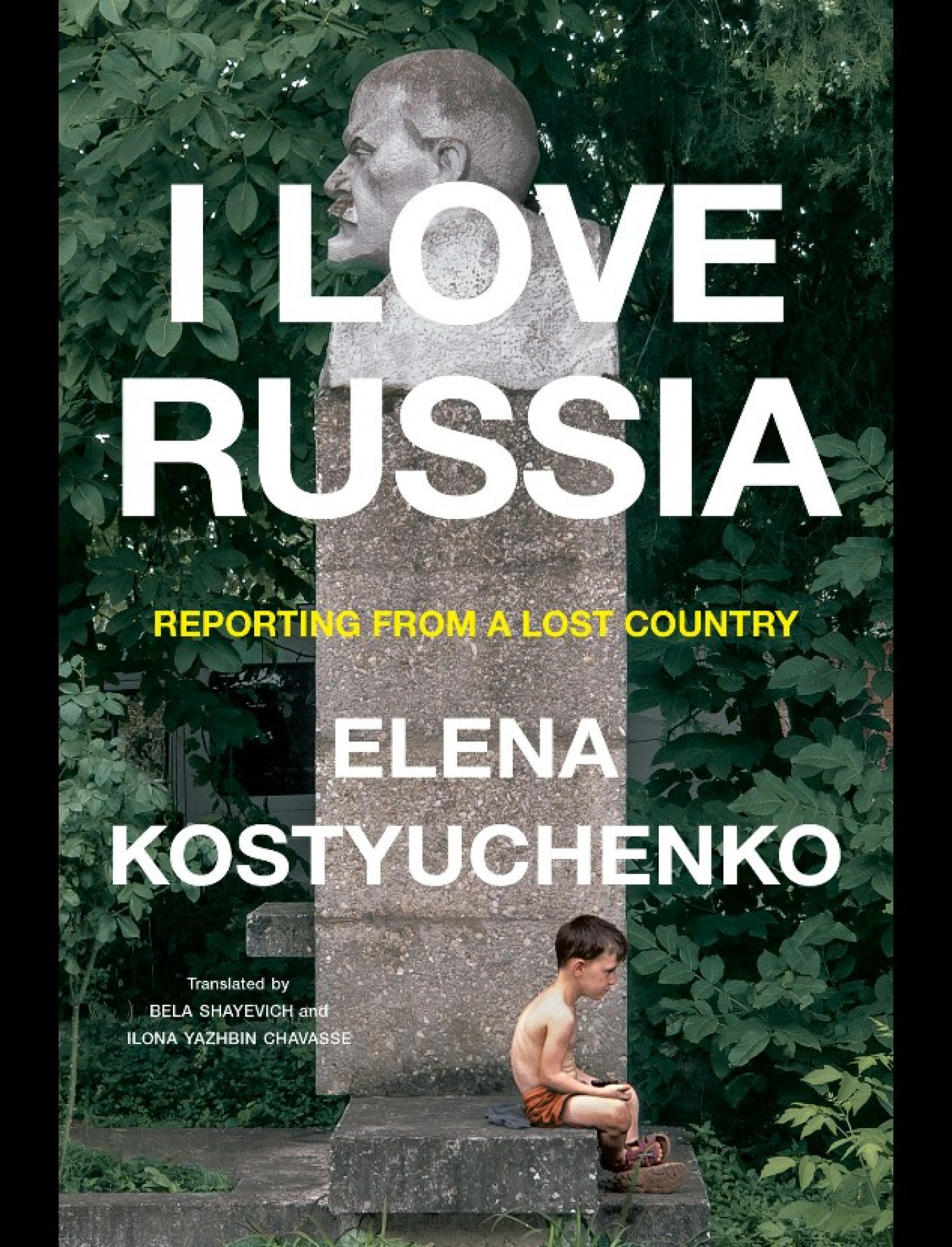

Kostyuchenko’s account of her stay in the internat provides the material for one of the chapters in her memoir-cum-essay collection titled “I Love Russia,” which has been elegantly translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse and Bela Shayevich. It has been shortlisted for the 2023 Pushkin House Book Prize.

The many other topics explored by Kostyuchenko include rural poverty, environmental disaster, prostitution, the high suicide rates that blight Russia’s ethnic minorities, homophobia, terrorism, human rights abuses, and, perhaps most graphically, the war in Ukraine.

But the big question to which “I Love Russia” provides helps provide some answers is why Kostyuchenko’s homeland has descended into full-blown authoritarianism – she calls it “fascism” – and why it is prosecuting such a terrible war on neighboring Ukraine.

In her 17 years working as a reporter at independent media outlet Novaya Gazeta, Kostyuchenko has had a ringside seat to witness this transformation. She has written many articles on the power of the state, and the Kremlin’s indifference to human life. She’s documented official brutality on dozens of occasions. As a gay woman, she has even herself been on the receiving end of violence, for example when she was assaulted at LGBTQ rights protests in Moscow.

Kostyuchenko has been unable to return to Russia since she left the country in 2022 to travel to Ukraine to report on the full-scale invasion.

But even in exile in Germany, she has not been safe. She was likely the victim of an attempted poisoning last year that left her unable to work for many months.

Kostyuchenko will join 23 other journalists for a fellowship program at Harvard University in the fall, where she will teach students and study postcolonialism and folklore, as well as conducting research on death and trauma.

Throughout “I Love Russia,” Kostyuchenko chronicles the dark heart of President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. And it is a task she accomplishes in unflinching, gut-wrenching detail.

In one chapter, the reader meets a 17-year-old prostitute, Laila, working on the outskirts of Moscow, who says she can have sex with 17 men in one night.

In another, Kostyuchenko describes the bodies of two sisters in a morgue in Ukrainian city Mykolaiv. They were killed by Russian shelling. “The younger girl is three years old and lies on top of her sister,” she writes. “Her jaw has been tied shut with gauze, her hands tied together to rest on her stomach. Little red wounds from shrapnel cover her body.”

After spending the two weeks in the internat, she asks herself what she now thinks about Russia system of institutions. “I have only scratched the surface of hell,” she replies.

“I Love Russia” is made up of different essays, including long-form articles first published in Novaya Gazeta, and chapters of memoir about Kostyuchenko’s own life – growing up, coming out, buying an apartment, arguing with her mother.

For her reporting, Kostychenko has traveled all over Russia, and perhaps the most revealing parts of the book are her depictions of the remote, poverty-stricken communities in Russia’s regions where violence is a daily occurrence – and how starkly they contrast with affluent Moscow.

“It was really scary out there, beyond the [Moscow] ring road,” she writes.

From "I Love Russia. Reporting From a Lost Country

Chapter 12

It’s Been Fascist for a Long Time (Open Your Eyes)

It was March, the end of March. Vera Drobinskaya, mother of seven adopted children, posted some photographs on her blog. They were blurry. A cemetery, just-melted snow, low, tender grass. The graves were nothing but unmarked heaps: no crosses, no tombstones, no names. Vera claimed that these were the graves of the children from Raznochinovka. “Some of them seem to be mass graves,” she wrote.

Raznochinovka is an internat, a live-in facility for children with mental disabilities. An investigation by the prosecutor general’s office showed that forty-one children had died there in the course of a decade.

I think I asked to go there myself.

Astrakhan is in the very south of Russia. Steppes, feather grass growing taller than you. The Volga here runs at full strength and spills into a hundred arms. The sun is so bright that you’re always squinting, searching for shade.

Vera lives in a small wooden house. It’s filthy and cramped. I see all of her children at once. Nadya, Roma, and Masha are reading. Tavifa is changing into a new dress. “She’s such a coquette,” Vera says. “If she doesn’t change clothes four times in a day, it’s all been in vain.” Misha is sitting at Vera’s feet, watching us anxiously. In the yard, Kolya and Maxim are taking turns on a skateboard.

All of Vera’s children are said to have neurodevelopmental disorders.

Nadya, Roma, and Misha came from Raznochinovka. Kolya, Maxim, and Masha came from a regular orphanage but were about to be transferred there when Vera saved them. Vera took Tavifa to Germany for surgery, then adopted her.

Vera is a doctor, a neonatal specialist. She says that she first found herself at Raznochinovka nine years ago. She went with an Italian woman who hadn’t managed to get her adoption papers together in time, so the child was sent there. “He died that same night. They were so happy to tell her. . . . The nannies took us on a tour. It was a Saturday, no one in charge was there—they were still fearless back then. The ward for the bedridden. Children lying on the floor, on plastic sheets. Some of them tied to their beds by their feet. The nannies said, ‘So they don’t run away.’ But aren’t they supposed to be bedridden?”

That was the first time that Vera saw Misha. He was tied to a bed with nylon stockings and chewing on his hands. Vera adopted Nadya and Roma along with Misha. “The nannies said that they didn’t understand why they were there, they were totally normal.”

“It was so hard at first. The children could only communicate in a mixture of swearing and gestures. They didn’t want to go to school, they would shout, ‘We are retards, we don’t need to!’ You’d raise your hand to caress them and they would cower, expecting that you were going to hit them. They’d never known anything but cruelty. Misha didn’t walk back then, he could only crawl. One time, I asked Roma to help get him into the kitchen, and he started kicking him in the stomach, to kick him out of the room. I grabbed Roma and shouted, ‘No! You can’t do that!’ He was so shocked!”

Vera keeps talking and talking, telling me how a Polish priest started her on volunteering, how at the hospital where she worked, infants would die for lack of the right formula, how she had been planning to adopt an eighth child from Raznochinovka, but child services rejected her application, how Misha had been injected with Thorazine and when she wrote to the prosecutor general’s office about it they said that the Thorazine was to treat epileptic seizures. “Thorazine doesn’t treat epilepsy. They inject them with it just to make them lie still.” My pen runs out of ink; I get out the next one to keep taking notes. The children are watching Harry Potter. I think to myself that this can’t all be true, everything she is telling me, it is too wild, too dramatic. On the other hand, she is a doctor, doctors are reliable, but then, she no longer works, now she is just the mother of seven children with disabilities—nobody sane would have taken that on. Was she getting revenge on the children’s home for not letting her have an eighth? Anything seemed possible.

I talk to Nadya. Nadya was seventeen and finishing the ninth grade. She started going to school when she was eleven, after Vera adopted her. They overturned her diagnosis of “mental retardation.” Nadya tells me about the orphanage. The schedule was simple: In the morning, they would “get dressed, line up for attendance, eat breakfast,” and then they would be put in the playroom. That’s where they usually spent the whole day, though sometimes the nannies would take them outside. “The yard had a big gazebo, that’s where we sat.” She says, “I was illiterate. But they did teach us embroidery.” She talks about how one of the nannies slapped her for bringing a kitten inside. “They also hit you when you went in your underwear . . . or if they thought you stole something. One time, one of them yelled at me, ‘You stole my pen!’ and pushed me on the floor. . . . If you attacked a nanny, they’d give you pills and tie you down to a bed, then you slept all day. But I never did that. It was too dangerous.

By evening, a lot of them were already drunk.” She says, “One day, they turned out all the lights before we had time to make it to bed. One nanny was in a hurry, they were having a party. She picked up a stick and started swinging. She got my head and my fingers. But it wasn’t her fault! She didn’t even see who she was hitting, the lights were all out. Maybe she was just clearing a path for herself through us all.”

Vera sits back down with us. “The regional psychiatrist would say to me, ‘But they’re not normal.’ He’d go, ‘Compare one of them to a regular child, you can tell right away.’ I’d say, ‘Take a regular child and send him to Raznochinovka for nine years. Then try comparing them.’ ”

Vera puts the kids in the van and we head down to the Volga. The kids run straight to the water. Masha splashes by the shore. I remember how when Vera brought Masha home, it turned out the girl had a short frenulum that made it difficult for her to talk. “And that was the whole reason why they decided that she was mentally disabled. The main determining factor for landing in there is random chance.” How can that be? I sit on the shore thinking and thinking. I end up with a sunburn. I am on fire, I want to throw up, my skin is bright red, I can’t touch it.

I don’t remember how I found Svetlana. Svetlana had her son admitted to Raznochinovka herself. “I had no choice. It was only because I didn’t have a choice. Everything in our house was broken, he destroyed everything. Three times, he dropped this dresser on himself. He’d try to run out onto the balcony.” We walk through her trashed apartment while she explains how she took him to a rehabilitation center in a neighboring town, how she worked nights doing the books for a salon so she could watch her son during the day. She wants me to know that she’s a good mother, that it’s not her fault. In Russia, there’s no support for families with children like this. When Svetlana would go and see doctors, they’d tell her that her son was incurable, that all she could do was have him admitted to an internat. At Raznochinovka she was told that she could only have him admitted if she signed over her parental rights. “That’s why I’m legally no one to him at this point,” she says. She visits him. “He’s lost weight, he’s like a skeleton. All covered in bites and wounds. They tell me they bite themselves. But he’d never bitten himself before. All he does is hug everyone. Maybe that’s why they bite him? He’s changed so much. He turns on the lights everywhere. He is afraid of water now—before, you couldn’t get him out of the tub. He has stopped crying, he doesn’t cry anymore. How can I find out what’s going on with him in there? He doesn’t talk.”

Excerpted from “I Love Russia: Reporting from a Lost Country" written by Elena Kostyuchenko, translated from Russian by Bela Shayevich and Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse and published by Penguin Publishing Group. Copyright © 2023 by Elena Kostyuchenko. Translation copyright © 2023 by Bela Shayevich and Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information about the author and book, see the publisher’s site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.