Russians have always like meat roasted on a spit. But it was never called shashlyk or kebabs. Oddly, today shashlyk is considered by zealots of Russian cuisine as something borrowed. But when you look more closely, the technique was used by our ancestors many centuries — if not millennia — ago.

Roasting meat over a fire is the oldest way of cooking it. In Russia, meat cooked this way was called "spit-roasted." The Domostroi (1550s) contains several references to it. For example, in the section "Easter Meat" the authors give instructions for serving spit-roasted swans, beef tongue and lamb brisket.

Ancient habits do not go away without a trace. And Sergey Drukovtsev's 1773 "Home Economics” recommends:

"Although everyone knows how to roast meat, I want to mention various kinds of meat. Animal meat and game should be soaked in fresh milk or water for a day so that the meat becomes whiter and tastes better. Then lard the meat with pork fat as needed, roast on a spit, sprinkling game with lemon juice as it roasts. Serve the roasted meat with a variety of salads, asparagus, chicory, olives, different cucumbers in wine vinegar, sturgeon black grain caviar, salted plums and lemons..."

And in "Russian Cookery" by Vasily Lyovshin in 1795-1798 we find the following:

"Cranes are roasted on a spit with or without basting. The roasted crane can then be used to make a delicious and even more nutritious chowder when the crane is old and the meat does not become completely tender while roasting.”

The Russian word шашлык (shashlyk) is a distortion of the Turkish word "shish," which means "spit" (the rod for roasting). Russians learned the word and process in the first half of the 19th century when they conducted military campaigns in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia.

The now-forgotten Russian writer Daniil Mordovtsev (1830-1905) wrote in his novel "By Iron and Blood" about the turbulent times of the conquest of the Caucasus under Yermolov:

In the evening the whole city was illuminated. Everyone was happy about the safe end to the campaign.

“What lamb, brothers!” said a boy from the Apsheron Peninsula who was sitting by the fire and nibbling on a shashlyk bone.

“Tasty, eh?” smiled Uncle Nazarych.

“Uncle, it tastes so good I’d go off on another campaign again in the morning just to have this again tomorrow evening.”

“That’s right,” a third soldier said. “It’s easier to fight when you know good food is waiting for you.”

Romanov sheep, once the standard and most widespread breed in central Russia, were good for everything: meat, fur coats and wool. But this actually meant that the sheep weren’t the best in any category. No wonder the shashlyk from sheep bred for meat tasted fabulous to simple soldiers who’d grown up in villages.

News of this shashlyk from the Caucasus began to reach the Russian capital cities. The famous cook Gerasim Stepanov published several cookbooks in the 1830s and 1840s. In 1837 he published a collection called, “Experienced Chef with Additional Specialties in the Asian Table or Oriental Gastronomy.” One recipe was for "sheshlyk,” described as "a birch stick 2.5 arshins long, round, cleanly and smoothly planed. It is sharp at one end so that it a goat or lamb can easily be put on it.” So here he called the skewer “sheshlyk,” not the meat.

One of the most famous kinds of shashlyk before the 1917 Revolution was Kars-style shashlyk, which appeared in Russia after the capture of the Turkish fortress of Kars by Russian troops under the command of General Nikolai Muravyov in 1855.

Above: “Surrender of Kars, Crimean War, November 28, 1855” by Thomas Jones Barker. General of Infantry Nikolai Muravyov, left, accepts the surrender of Kars. In the center is British Colonel Sir William Fenwick Williams, commander of the Turkish fortress garrison.

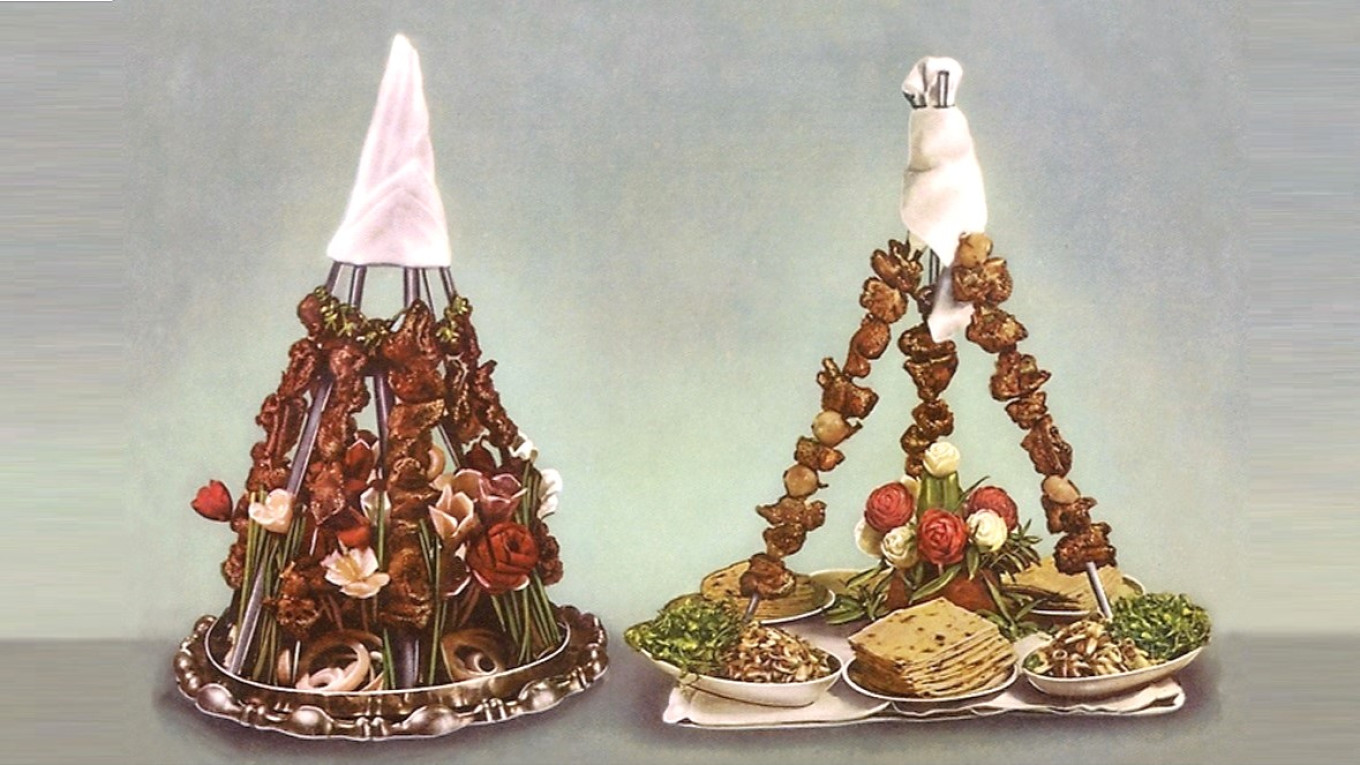

The siege lasted five months, so the Russian troops had time to get to know the local culinary traditions. The area around Kars was inhabited mainly by Armenians, and they made shashlyk from large pieces of meat. They used mainly lamb loin along with rump steaks, which were quite fatty and made the shashlyk juicy.

By the end of the 19th century in the Russia, culinary experts had a good idea of why roasted meat was so popular and the best way to roast it. "How to Stew, Roast and Fry Deliciously and Cheaply" was the name of the book published in Moscow in 1894, where shashlyk was already the subject of a separate analysis:

"The best way to roast meat without any utensils is on a spit. The flavor of meat and poultry prepared this way is incomparably better than meat fried in a pan or especially stewed in a pot. The fame of shashlyk comes from the fact that when roasting meat on a spit, the heat from the coals quickly seals the meat and immediately forms a crust, preventing the juice from flowing out, so it remains entirely in the meat. Whereas in other ways of frying, the best part of the meat seeps out and becomes gravy.”

The first recipes for shashlyk from the Caucasus adapted for the Russian public began to appear. For example, here’s a recipe from I. A. Ivanova's book "A Gift Cookbook For Young Housewives” (1899):

"Cut slices of very fat lamb, rub it with salt, pepper and finely chopped onions, impale the pieces on a metal rod, roast over the fire, constantly turning. When it is done, put it on a dish and sprinkle it with well-boiled rice until crumbly."

But, of course, roasting meat on a skewer wasn’t adopted into Russian cuisine from unknown nomads somewhere. It was the very first way to prepare meat and other food in our cuisine. And it hasn’t lost its appeal over the past centuries and millennia.

Unfortunately, given Russian climatic conditions, this is only a summer pleasure enjoyed out in nature. But for people who can’t get away to a dacha there is a way to have the same feeling of standing in the heat of the fire, swatting mosquitoes and salivating at the scent of roasting meat. We can’t promise mosquitoes, but delicious meat is guaranteed.

Oven Kebabs

Instructions

- Choose your meat — we usually buy pork shoulder — and make sure you have a lot of onions. You will also need soy sauce, vegetable oil, pepper and a little sugar, preferably brown cane sugar.

- Preheat the oven to 220°C / 425°F. Cut the meat in pieces as you usually would for kebabs. Slice the onions into large rings. Put the meat and onion in a bowl

- Get a separate bowl for the soy sauce and oil. You'll need enough to moisten all the meat. You don't need a lot of oil — just enough to baste each piece. No salt: the soy sauce is salty enough.

- Mix the soy sauce, oil, pepper in the bowl; add a pinch of sugar. Stir until it all dissolves. The sugar gives the crusty caramelization; the oil keeps the kebabs juicy. Then pour the mixture over the meat and onions and mix everything thoroughly with your hands. Leave for half an hour to marinate.

- Then put the meat and onions on a baking tray and place in the oven for about 15-20 minutes. You will see when the meat has the right golden color, when it sizzles and smells great. If necessary, give the pieces a stir or turn them over.

- Serve kitchen kebabs with a vegetable salad, just like outdoors by the grill.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.