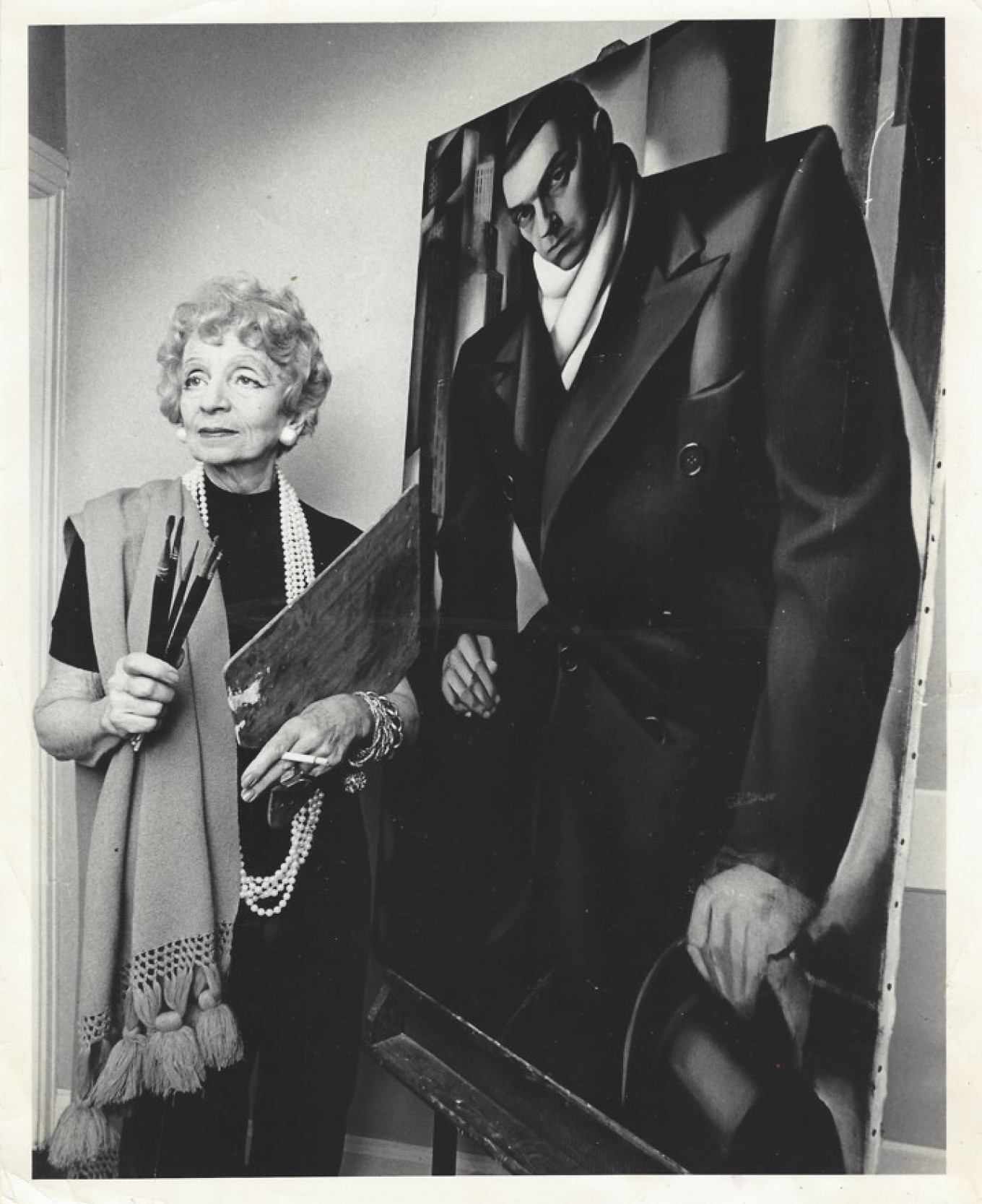

The artist Tamara de Lempicka is having a moment.

The glamourous aristocratic Russian refugee artist (1894–1980) best known for her Art Deco portraits, is the heroine of the musical “Lempicka,” which opened on Broadway on April 14. Starring Eden Espinosa, the show is directed by two-time Tony Award-winner Rachel Chavkin. It is an extravagant production because, as Chavkin said, “We wanted to make a show as aesthetically spectacular as her work is.”

In October a major show of Lempicka’s works will open at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The show, co-curated by scholars Gioia Mori and Furio Rinaldi, will span the artist’s entire career from the 1920s to her final years in Mexico. It will include more than 100 works from the Paris Centre Georges Pompidou, international museums, and U.S. and European private collections.

A tentative biography

Establishing Lempicka’s biography is no easy matter. The most authoritative expert on the artist, Gioia Mori, told The Moscow Times: “She loved to manipulate reality.”

Art critics do not even agree on her date and place of birth. Lempicka seems to have lied about her age to be eight years younger than she actually was. Mori believes Tamara Rozalia Gurwik-Górska was born in Moscow. So does biographer Laura Claridge. Other scholars think the painter was born in Warsaw. Claridge identifies her father as Boris Gurwik-Gorski, a successful Russian Jewish merchant who disappeared when Tamara was a toddler. The artist’s granddaughter, Victoria de Lempicka, once told Anne Paddy, a prominent collector of Lempicka’s work, “Her mother said, ‘We will never speak about him again in this house!’”

Paddy believes that the obfuscation was because Lempicka feared discrimination. “Jewish persecution was a tragic, stark reality, and the constant instability of Eastern Europe was delicate and highly political. Her mother, Malvina Decler, a Pole of French descent, had married a Russian, and in Tamara’s mind, it was probably safer to choose Warsaw.”

Tamara’s extended family was split between Warsaw, St. Petersburg and Moscow.

In 1910, Tamara moved in with her aunt in St. Petersburg for several years. Her Aunt Stefa had ties with the imperial family and the artist’s grandmother lavished attention, expensive clothes, and foreign travel on her. One night in 1911, the adolescent Tamara met her future husband, Tadeusz de Lempicki, an attorney from a noble family, at a fancy dress ball organized by her uncle. Tamara came wearing a Polish peasant costume with a goose on a lead. In 1916, she convinced her uncle to allow her to marry Lempicki.

Their only daughter, Marie Christine, known as Kizette, was born in the same year. Tamara and her family remained in Petrograd after the 1917 Revolution, and Lempicka became acquainted with Cubism and Futurism.

“There are no records of personal artistic works other than entries in her sketchbook during these years,” Paddy said. “Tamara was a young woman pursuing a husband at the time. But she visited museums, the opera, and other cultural events in St. Petersburg, and influences from that time can be seen in her future work in Paris.”

In December 1917 Tadeusz Lempicki was arrested by the Soviet secret police. Thanks to powerful connections, he was released, and the family soon settled in Paris, where many Russian émigré artists brought new life to the art scene.

Conquering Europe

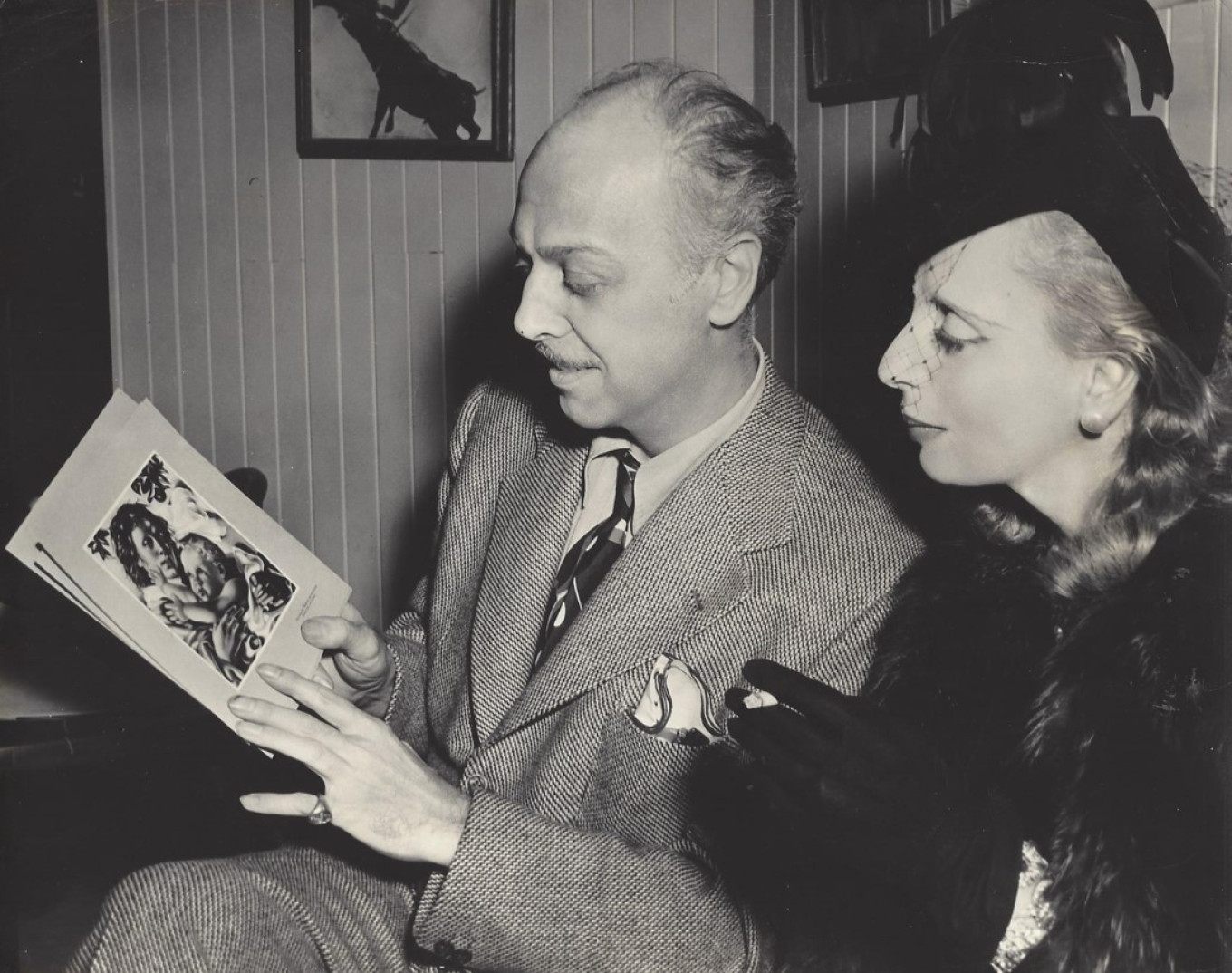

The exuberant Paris of the 1920s welcomed Tamara with a high society mixed with the Cubist, Futurist, and early Surrealist avant-garde. She became a portraitist, capturing the art Zeitgeist by distilling the highly geometric Art Deco design that reached its apex in the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris.

But according to the artist’s granddaughter, Victoria de Lempicka, President of Tamara Art Heritage, there were earlier influences on her work. Although her grandmother was educated in St. Petersburg and Lausanne, “her heart danced with life when she was in Italy, the first time at age 10 with her grandmother,” she told The Moscow Times. Tamara adored Botticelli, Pontorno, Michelangelo and Fra Lippi. “Her unique style combined the Italian classicism of the Quattrocento with the curved volumes of Futurism’s Marinetti,” Victoria said.

Her Russian past played a role in her artistic development as well. “The moment she arrived in Paris,” Mori said, “Lempicka started working as an illustrator for fashion magazines. Many Russians and even members of the Russian nobility were involved in the Paris fashion industry. This included Prince Gavriil Romanov and his wife Antonina who by 1924 established their own fashion house.” Lempicka, part of their circle, painted a famous portrait of Prince Gavriil in 1927. In the early 1920s she painted several still-lives depicting old Russian wooden toys: “L’oiseau rouge” and “Nature morte à la poupée russe,” objects whose silent voices blend into a threnody of nostalgia.

Lempicka’s work ethic and output were phenomenal. She would do three long sessions with different sitters daily while listening to Wagner at the highest volume. Many say she was addicted to cocaine.

“There are many references to drugs in the stories she told about her life. However, I don’t personally believe she was ever addicted to drugs,” Paddy said. But no doubt, “she threw lavish parties for guests and attended those of others where the champagne flowed freely, and drugs were available. Her one known vice was smoking cigarettes, which she did incessantly, and the ensuing consequences eventually contributed to her death.”

In 1925, a Milan art gallery, Bottega di Poesia, hosted Lempicka’s solo debut show. On the occasion, the artist used the moniker Lempitzka. Until then, she had signed her canvases as Łempitzky, using the masculine version of her married last name. Three years later the couple divorced.

There is a feminist factor in her paintings, and it is evident that Tamara admired females, “especially successful and strong women,” says Paddy. “Even in commissioned portraits, the vibe of feminism shows through. Whether a woman was independently successful like 'Suzy Solidor or a respected well-heeled matriarch like 'Madame Boucard' and 'Mrs. Bush,' Tamara always portrayed feminism as power.”

New shores

Lempicka married again in 1934 in Zurich to Baron Raoul Kuffner. Both were bisexual and agreed to an open marriage. At the beginning of 1939, the couple — both Jewish — emigrated to the U.S. In 1940, they moved to California, where they leased King Vidor’s villa in Coldwater Canyon, and Lempicka made friends with celebrities such as Greta Garbo and Tyrone Power.

Lempicka painted show business figures in Europe and the U.S., and she has been a favorite painter of Hollywood collectors such as Barbra Streisand, Jack Nicholson and Madonna. In 2020 her “Portrait of Marjorie Ferry,” a jazz chanteuse, set a new auction record for the artist, fetching almost $22 million.

She continued to work, taking regular trips to Europe after WWII. The artist lived until 1980 in her villa in Cuernavaca, Mexico, her last home. Paddy explains: “In Tamara’s later years, her daughter Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall oversaw the collection and preservation of her archive, helped with business and medical affairs, and ultimately granted her mother’s last wish for her ashes to be scattered over the volcano Popocatapetl.”

“The world is now finding a new appreciation for her entire oeuvre,” Paddy said. “Tamara’s journey is everyone’s journey… She spans generations, races, religions, genders, and nationalities and has become the symbol of determination, independence, success, and survival.”

Paddy is confident that the musical “Lempicka” will bring a whole new audience to learn about her art and life. “Tamara’s great-granddaughter Marisa and I were in tears at the end of the first act. Tamara is on the stage she was born to be.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.