Space flights are definitely important and certainly exciting. But even cosmonauts (and astronauts) flying in space need to have lunch. Of course, when Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov blasted off the launchpads as the first and second Soviet citizens in space, they weren’t thinking about food. But later space nutrition became very important in longer flights.

The best known cake of the Soviet era is the Napoleon cake. But no matter how delicious it is, people like a change from time to time. Many home cooks wanted to diversify their holiday dessert menu, including with the beautiful Flight Cake, which probably got its name when Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space on April 12, 1961.

The name tells you what the cake is: a light, airy flight of flavor and pleasure. But this is a cake eaten on earth. Creating food for space travel turned out to be a task of great complexity.

Food for space was a totally new area for every kind of scientist. No one knew how the most common foods would behave in weightlessness, and no one had any idea how the cosmonaut's body would respond, either. But specialists in Soviet space medicine found a solution by creating a unique, and to be honest, very unusual diet.

They began by carrying out tests in airplanes where they could induce weightlessness, but only for 20-55 seconds. In those seconds the testers tried to eat pieces of meat and bread and drink water and fruit juices. In the experiments pieces of food floated around the cabin. Liquids in weightlessness also behaved strangely.

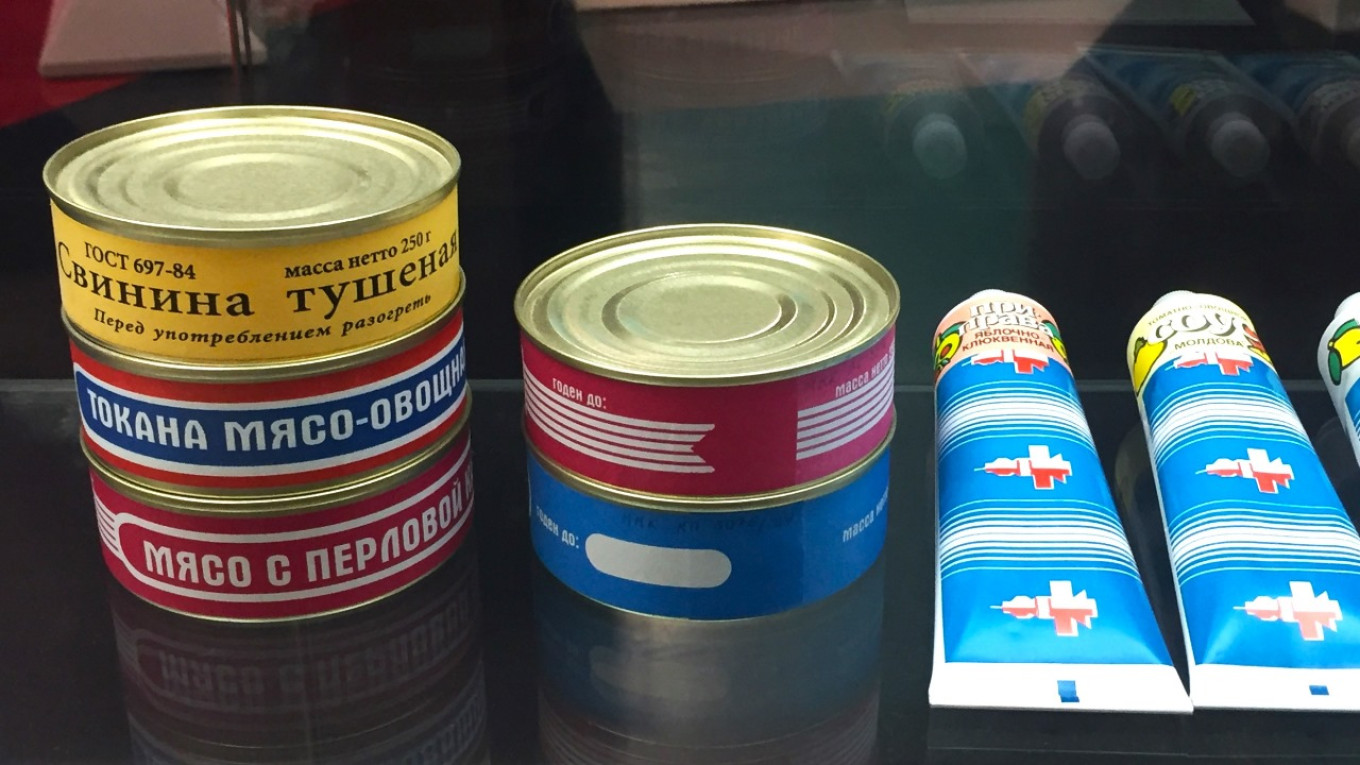

For the first space flights of Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov, the food was mostly puréed: pâtés, sauces and mashed potatoes. They were in 160-gram (5.5 oz.) tubes that looked like tubes of toothpaste made of aluminum with a special coating on the inside.

On later flights, onboard food included a variety of main courses: fried meat, meat patties, tongue, veal and chicken fillets. For the first time cosmonauts dined in space on pressed caviar sandwiches and sprat pies.

Of course, they didn’t forget bread — but it was baked in small balls that the cosmonauts could pop into their mouths so that they didn't take bites that would send crumbs floating through the cabin. Other solid foods were prepared the same way, and to this day they still bake little bread balls for space travelers.

Scientists in America followed the same path, also packaging food in tubes for space flights. In 1962, the American astronaut John Glenn dined on board the spacecraft Friendship 7 by squeezing out metal tubes of applesauce and mashed beef with vegetables into his mouth through a hole in his spacesuit.

But in the 1960s bars of dehydrated, freeze-dried food, which were convenient — and more normal — to eat, became more popular. This is what is taken aboard the Gemini and Apollo missions.

It's cold in space. But oddly enough ice cream didn’t work out on board. Even though “space ice cream” is sold in museum stores, ice cream has been in real space only once — aboard Apollo 7 in 1968.

And what about the traditional Russian question: How can you have a bite to eat without chasing it down with a drink? Alcohol in space is not a simple subject. There have been experiments. For example, Buzz Aldrin was the second man on the Moon and the first to drink wine there.

But today, drinking in orbit is officially forbidden. And not at all because of concerns about the behavior of astronauts. The fact is that alcohol can damage the water regeneration system. And that's much more serious.

In the USSR, the attitude to alcohol in orbit was more relaxed than in America. Cosmonauts on the Mir orbital station were allowed to drink cognac and vodka in small quantities. But there is a dry law aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

Today astronauts' choices are even more varied than on a restaurant menu. According to NASA, they can choose from more than 200 varieties of food and drink.

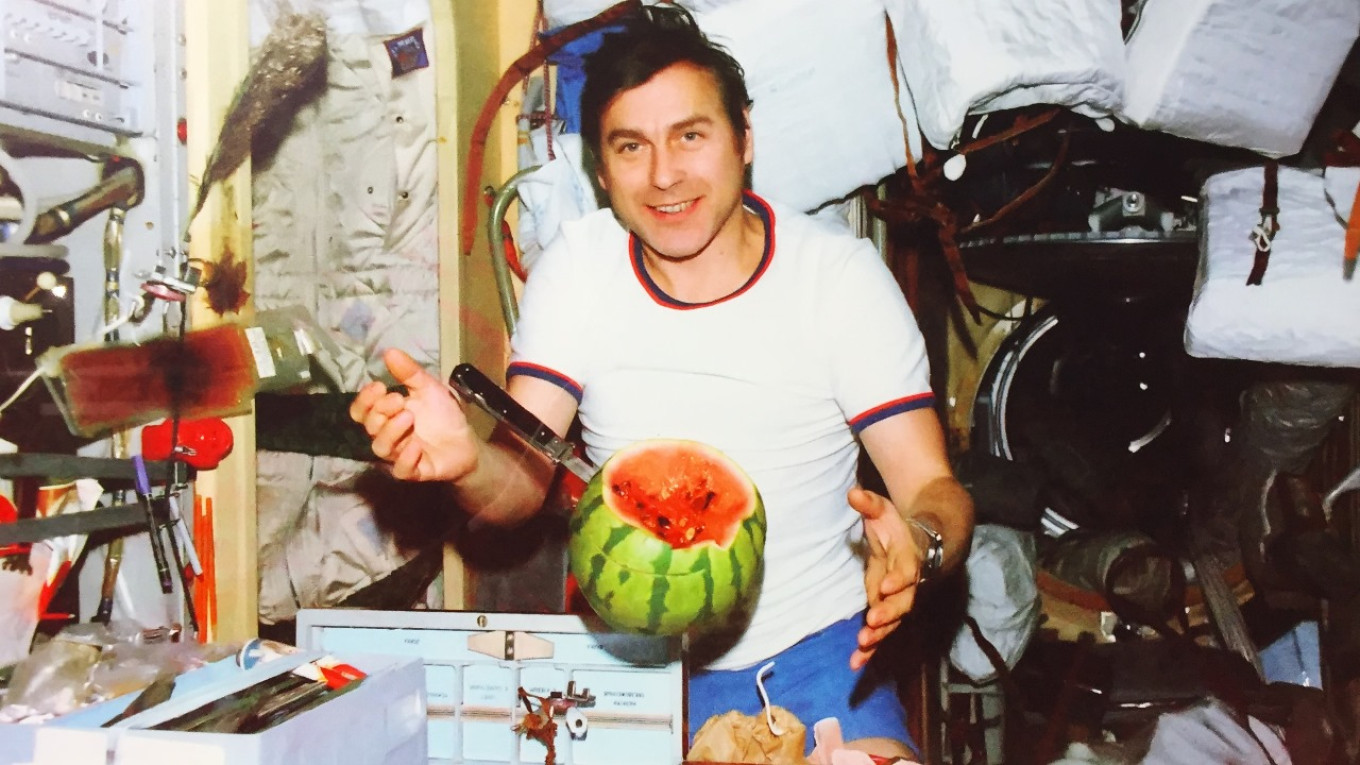

Above: Cosmonaut Alexander Alexandrov with a watermelon delivered to the Mir space station (August 1987). Photo from the Museum of Cosmonautics and Aviation in Moscow.

Today cosmonauts mainly eat sterile, freeze-dried foods in cans or tubes (the latter now only used for mustard, sauces and honey). They also eat fresh fruits and vegetables. They pour water into packages with freeze-dried products to reconstitute them before eating, and cans are heated in a special oven.

Food is modified to reduce its weight and volume. Fruit, fish and meat, for example, are heat-treated and irradiated to kill various microorganisms and enzymes. Nuts or baked goods go into space without any modification, but salt and pepper are liquified, while while coffee and juices are turned into powders.

The menu on the ISS is repeated every eight days. But the problem with space food is that it doesn't taste the same as it does on earth. In the first few days on board astronauts have high blood pressure and they lose their sense of smell. And the flavor of the food changes. That's why astronauts carry a lot of sauces, especially spicy ones.

In the past a flight would last only a few weeks, but soon space missions will last for years. NASA is already thinking about hydroponic laboratories where astronauts could grow vegetables, wheat and rice. A special challenge is to combat the monotonous diet. One solution is to allow astronauts to cook for themselves. Besides, cooking together also strengthens the team.

Unfortunately, for many years space travel has been a more theoretical concept in Russia. No one is dreaming of the “infinite universe” the way Sergei Korolyov — the Soviet Union’s chief rocket engineer and spacecraft designer — did in the past. Today the Russian leadership doesn’t think on that scale — they’re just figuring out how to hold on to power for another year or two.

But we on earth are thinking about space food and food about space, like this Flight Cake. In honor of Cosmonaut's Day, we photographed it against the background of a box of sweets from that first year of space flight: 1961.

Flight Cake

Ingredients

for the meringues

- 130 g (4.6 oz or 1 c) unsalted peanuts

- 5 egg whites

- 320 g (11.25 oz or 1 5/8 c) sugar

- vanilla

for the cream

- 1 egg

- 125 ml (1/2 c) milk

- 190 g (6.7 oz or ¾ c) sugar

- 215 g (7.5 oz or ¾ cup + 3 Tbsp) butter at room temperature

- 1 Tbsp brandy

- vanilla

- 1 tsp cocoa

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 180°C /355°F.

- Roast nuts for 15 minutes the preheated oven. If the peanuts are not shelled, shell them and chop before roasting.

- Lower the oven temperature to 100°C /212°F.

- Draw two circles with a diameter of 20-22 cm (about 7.5 to 8.5 inches) on baking paper. If both circles don’t fit on a baking tray, put them on two trays.

- Carefully separate the egg whites from the yolks.

- Whisk the whites to stiff peaks and, continuing to whisk, gradually pour in all the sugar, then add vanilla extract to taste.

- Set aside two tablespoons of the whipped egg whites and mix the rest with the peanuts.

- Divide the whites and peanut mixture in half and spread them in the two circles drawn on baking paper.

- Using a pastry bag or a teaspoon, pipe the reserved beaten egg whites into rosette shapes on the baking tray. After they dry, they will be used for decoration.

- Bake the meringues for 2 hours at 100°C /212°F degrees and cool completely in the oven.

- While the meringues are baking and cooling, prepare the crème charlotte. Whisk the egg with the milk and pour through a strainer (to separate out any lumps). Add sugar; stir and put on low heat.

- Stirring constantly, bring the custard to a boil and cook for 1 minute. Remove from heat and cool completely.

- Beat the butter until pale and fluffy. While continuing to beat, add the egg-sugar syrup a little at a time. Pour in vanilla extract and brandy.

- Mix two or three spoons of cream with cocoa for decoration. Spread the crusts and sides of the cake with cream frosting. Decorate with rosettes and cream with cocoa.

- Put the cake in the refrigerator for 3-4 hours before serving.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.