Not sturgeon or swans. Not solyanka soup or salad Olivier. The most enduring treasure of Russian cuisine is kasha — porridge made from grains. Many people consider it a simple or even primitive food. But over hundreds of years, grain porridges have evolved tremendously.

Porridge is the main contender for the role of the Russian national dish. If Russian cuisine was diverse in anything, it was in dishes made of products that grow in the earth. The most valuable of these are grains made into porridge or boiled until tender: oats, rye, wheat, barley, etc. In "Domostroi" (written in the 1550s), there are recipes for porridge made with products like herring or ham that seem strange to Russians today, and even experts can’t decide how herring porridge was made.

We will leave those dishes to the side and talk about our old acquaintances: pearl barley, millet and buckwheat.

Buckwheat

Buckwheat came to ancient Rus about 1,000 years ago, perhaps brought home from Byzantium by Russian travelers. Buckwheat in Russian is гречка (grechka), which tells you where it came from: at that time everything from Byzantium was called “Greek.” But it became a part of our diet only at the end of the 16th century after Ivan the Terrible annexed the Volga region and Kazan, which were then the main areas growing buckwheat.

In ancient times buckwheat kernels were stripped and separated from the stem. In this raw form it is gray-green — you can find raw buckwheat in stores today, since it is considered healthier. In the 1950s in the U.S.S.R., the kernels were roasted before being packaged and sold. This not only made it possible to store for long periods of time, it turned the grains brown and gave them a light nutty flavor.

Pearl barley

Today when people speak condescendingly about the “pearly” grain, we forget that it’s called pearl barley for a reason. Tender and tasty pearl barley porridge was a favorite of Peter the Great. Perhaps his cook, the German Johannes Velten, thoughtbarley wasn’t a royal enough name for the porridge. So he spiffed it up “in the English manner” and called it pearl barley.

Threshed barley grains come in three categories: whole grain barley — the least cleaned and polished — is called “yachka” in Russian; polished grains are called pot or scotch barley in English and pearl grouts in Russian, and the most highly refined grains are called pearl barley in both English and Russian.

The most healthful is whole grain barley, which also cooks the fastest. Scotch barley takes a long time to cook, but when cooked in milk it is as light as a feather. Pearl barley is the most beautiful and cooks faster than scotch barley, but in terms of nutrients, it is inferior to both whole grain and scotch barley. The polishing leaves few nutrients and vitamins. But it can be used to make a dish similar to risotto. Do not laugh, it even has a similar name: perlotto.

Millet

For centuries in Russia the most festive dish was not buckwheat or rice, but ordinary millet porridge. Even the monks at the Solovetsky monastery who were accustomed to good food had millet porridge as their best lunch of the year on Easter Sunday. That’s right: salmon with sour cream, soup made with halibut and millet porridge with milk.

And why not? This golden grain makes delicious porridge: baked in the oven with milk and butter, or Lenten millet porridge with nut butter. Blinis made with milky millet are fluffy and delicious. Unfortunately, they are all but forgotten.

Millet is filled with healthy microelements and vitamins, but it also contains a high oil content. This is why it quickly goes rancid when it is improperly stored. When you buy it, be sure to pay attention to the date of packaging. It is better to buy millet in a transparent bag so you can see its color, which should be bright yellow, with no crushed grains or dust at the bottom of the bag.

Some people find millet bitter. This is easy to fix. Before cooking scald millet grains with boiling water, boil for a minute or two, and then drain. Only then cover with milk and and cook until ready.

***

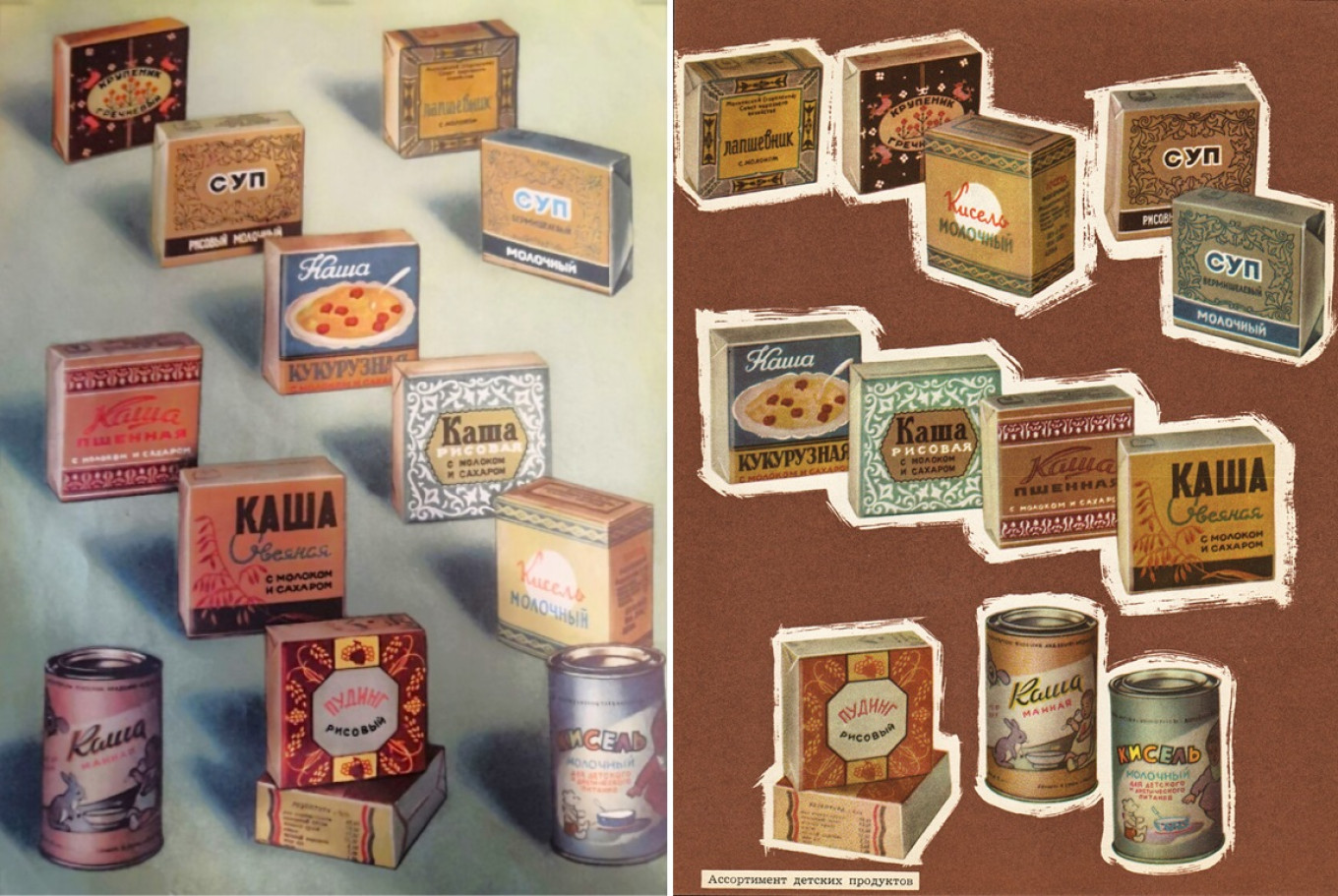

In Soviet times, the attitude to porridge changed somewhat. For some reason people stopped making sturgeon and veal with grains. But the simplest porridge — millet and pearl barley — became the ideal of folk cuisine, containing all the ancient wisdom of the people. They were perceived as being the most healthy foods, filled will everything the body needed. This is understandable. Peas, millet and semolina were perhaps some of the few products that were not in short supply in the U.S.S.R. Even buckwheat was not always freely available. So porridge made from these grains were promoted by propaganda.

There are many reasons for the popularity of grains and porridge in Russia today. First of all, it is a traditional food, and nostalgia for Soviet times and the meals our grandmothers made us add new overtones to this love. Secondly, because grains are so good for you, the fashion for healthy eating makes grains a priority. And finally, let's not forget that grains are also inexpensive. And in the current protracted economic crisis, many Russians have to resort to them.

Our grandchildren love porridge, especially if you fantasize a bit when preparing it — like we did with this very simple but delicious dish. Sweets are allowed during the Lenten fast, especially when the sweets are full of vitamins — just what you need in the spring.

Semolina Berry Mousse

Ingredients

- 2 cups cranberries

- 4 Tbsp semolina

- 200 g (1 c) sugar

- 1 liter (1 quart) water

Instructions

- In a saucepan, crush cranberries, pour hot water, add sugar.

- Bring to a boil and cook for 3-4 minutes. Strain through a sieve.

- Return the liquid to the burner, bring to a boil and add the semolina, pouring it in a thin stream.

- Stirring continuously, boil until you have a thick semolina porridge.

- Cool and whip with a blender to a fluffy mousse.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.